Japanese-Canadian Internments

Throughout the war, Canada interned various populations of people who were considered a risk to Canadian national security. People who came from belligerent enemy countries were deemed enemy aliens. However, this designation was also given to people with backgrounds in foreign countries who had actually been born in Canada. Internment was not unique to this conflict and was achieved through the suspension of civil rights during the invocation of the War Measures Act. During the First World War, Canada interned many groups of people including Austro-Hungarians, Germans, Ukrainians, and Turks. Ukrainian-Canadians remained interned until 1920. During the Second World War, the War Measures Act was enacted again and Canada interned Germans, Japanese, Italians, Jews, and Mennonites. Sometimes this included women and children. All the people interned were deemed to pose a threat to Canadian national security, either through their connection to an enemy country or their objections to the conflict. Many Jews fleeing Europe were interned upon their arrival in Canada. Many Canadian Mennonites were also interned due to their conscientious objections to the war.

In November 1941, Canada sent troops to Hong Kong as a precaution to potentially defend British colonial holdings in Asia. Japan had been at war with China since 1937 but up to this point had not engaged in acts of war against western countries. Nevertheless, Britain recognized the vulnerability of British territory in Asia should Japan decide to invade. The Canadian troops in Hong Kong were ill-prepared should an attack come from Japan, but many thought an attack would not happen and even if it did the prevailing notion of white superiority had Canadian and British military leaders thinking they could easily overcome a Japanese invasion. Of course, an attack did come. On December 7, 1941 Japan bombed Pearl Harbour, Hawaii, and six hours later highly trained and experienced Japanese troops invaded Hong Kong. Thus, Canada, and the rest of the Allies, were at war with Japan.

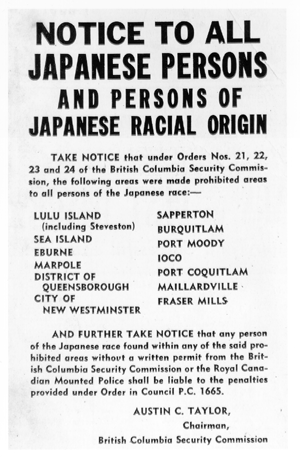

Anger toward, and fear of, Japanese-Canadians was felt most acutely in British Columbia, which was just across the Pacific Ocean from Japan. Politicians in BC were calling on the federal government to deal with the Japanese people living on the coast, which resulted in Prime Minister King ordering the transfer of all adult Japanese men to labour camps in January 1942. However, the weather prohibited their immediate removal. But the order itself made the people of British Columbia believe that their fears were confirmed, and that the Japanese did pose a threat to their security. Under even more pressure from politicians and the public in British Columbia, and emboldened by the decision in the United States to intern the Japanese, Prime Minister King announced that all people of Japanese ancestry would be removed from a 160-kilometre zone on the Pacific Coast in February 1942. This decision was fundamentally a political choice, as officers in the military at the time indicated the Japanese-Canadian population did not pose a significant threat to Canada.

A NOTICE FROM THE BRITISH COLUMBIA SECURITY COMMISSION REQUIRING THE EVACUATION OF JAPANESE PEOPLE FROM CERTAIN AREAS. IMAGE FROM WIKIMEDIA COMMONS.

Over 20,000 people of Japanese ancestry were uprooted during internment, the majority of whom had been born in Canada. It was not just able-bodied adult men who were removed, but all people of Japanese-descent, including women and children. People were moved out of the 160-km zone and temporarily housed in camps, including at Hastings Park. Over 8,000 people were moved through Hasting Park where women and children were housed in the livestock barns. After these temporary camps, Japanese-Canadians were shipped out to the interior of British Columbia to small towns like Kaslo and Slocan. Alternatively, Japanese-Canadians could work on sugar beet farms in Alberta and Manitoba. Men who were deemed resistant or troublemakers were sent to prisoner of war camps in Ontario. Japanese-Canadian property was also seized when they were interned. Beginning in 1943, the Canadian government started to liquidate this property. Houses, farms, business, boats, and other personal property was sold and proceeds went to funding the Japanese internment program.

As the war was coming to a close, Japanese-Canadians were given two options, to permanently resettle east of the Rocky Mountains, at their own expense, or to ‘return’ to Japan in which case the government would provide financial assistance for housing until the war ended. Many of the people interned had never been to Japan, as they had been born in Canada. Most decided to move east of the Rockies, but almost 4,000 left for Japan. Most of those who chose to go to Japan were first generation migrants to Canada, but over 1,000 people were children under the age of 16. Following the war Japanese-Canadians did not receive their property, or the proceeds of their sale, and were prohibited from returning to the west coast until 1949. Japanese-Canadians were not granted the right to vote until 1948.

ONE OF THE JAPANESE-INTERNMENT CAMPS IN BRITISH COLUMBIA. IMAGE FROM WIKIMEDIA COMMONS.

On September 22, 1988 Prime Minister Brian Mulroney apologized to Japanese-Canadians on behalf of the Canadian government. Furthermore, a new piece of legislation was drafted to replace the restrictive War Measures Act. The new Emergencies Act requires a state of emergency to be confirmed by parliament, it cannot just be called by the executive branch, and any actions taken during a state of emergency must be in line with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Though many different groups were interned during the war, the experience of Japanese-Canadians was shaped by racism in ways that the internment of others were not. There was some monetary compensation given to survivors, to a Japanese community fund, and to establish a Canadian race relations foundation. But there was never, nor can there ever, be a full compensation for the property and liberties that were forcibly taken away from Japanese-Canadians.