We’ve Been Here All Along

Traditionally, history in the western world has been recorded by the dominant European settler population. This has left huge gaps in stories, artifacts, and details surrounding the rest of the settler population and, of course, of the Indigenous communities as well. It is wrong to assume that an absence of formal recorded history points to a lack of significant contributions, however. In fact, every community adds important elements to every region of BC and Canada.

BC has been home to Black communities since the mid 1800s. Black families and individuals have been calling Coquitlam home since the 1960s, and Black people had been commuting to Coquitlam for work for many years prior to living here. They’ve been here all along, but finding the Black community in most official historical records has been challenging and frustrating. Except for in a few specific collections, they have simply not been included.

We’ve Been Here All Along is an online exhibit that recognizes a selection of stories and contributions from historic and contemporary Black communities, their achievements, and their struggles. It has been compiled through the generosity of those families and individuals who hold these histories safe. We are grateful for the guidance and support of those who have recorded what many official repositories do not include.

This exhibit has been created in collaboration with the African Descent Society British Columbia. We are also grateful for collections at the Saltspring Island Archives, the Barkerville Archives and the Royal British Columbia Museum.

Traces

With the exception of the Royal British Columbia Museum Archives and the Salt Spring Island Archives, searching through various archives for pictures of the area’s Black communities turned up very little. When images did turn up, there was little or no information about the Black people in them. But they were there.

A very close look at some of the photographs from earlier years in Coquitlam, New Westminster, and Vancouver reveal traces of our Black communities. Attempts were made at identifying some of the people in the following photographs with no success. The pictures are from various dates and places in Coquitlam and the surrounding area.

Who are they? Does anyone know these people or their stories?

Artifacts and Activists

The few artifacts in Coquitlam Heritage’s collection contain a tin toy, a uniform, a tablecloth, and a set of books that vaguely hint at the existence of a Black community. Local collector Ivan Sayers added to these with items from his collection. The uniform is a reminder that Black people also fought for our country, and the books illustrate the ease with which Black accomplishments were overlooked for much of this country’s history. The other items, sadly, are a commentary on the prevalence of, and disregard for, racism.

We have come to a point in time where certain behaviours and types of language are clearly identifiable as wrong. Racial discrimination is a recognizable evil, and many younger generations are rightly shocked if they hear or see discrimination based on nothing more than a person’s outward appearance. This is good. It shows we are headed towards a better society. One question that could be asked, though, is do we move ahead, sweeping the vestiges of racism under the carpet of the past, or do we keep the reminders to illustrate wrongs done and how not to behave?

David Pilgrim, founder of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia in Big Rapids, Michigan, believes that the objects should be preserved in order to show how far we have come, and to serve as a reminder to remain vigilant. Other collectors of these items include Oprah Winfrey and Whoopi Goldberg. The National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee, where the diorama of Rosa Parks (below) is on display, also has a collection of racist memorabilia.

Rosa Parks

A diorama of Rosa Parks

Rosa Parks having her fingerprints taken

Racist Depictions

This “Little Joe'' money bank illustrates how Black people were portrayed as racially stereotyped images. “Little Joe” shows subservience and an eagerness to please, both traits that many white communities expected of Black people. First manufactured by the Shepard Hardware Company of Buffalo, New York in the late 1800s, various versions were created around the world.

Amos ‘n’ Andy was a very popular radio program, originally broadcast from WMAQ in Chicago in 1928. It featured two black men, Amos Jones and Andy Hogg Brown, voiced by two white actors, Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll. The show ran both as a radio serial and television show from 1928 until as late as 1966.

The programs followed the antics of Amos ‘n’ Andy, two Black men that epitomized their largely white audience’s racist perceptions of Black people. Having moved to Chicago from Georgia, the two men began the Fresh Air Taxi Company. Portrayed as dim-witted and generally lazy, the characters were hurtful stereotypes that reinforced already negative perceptions of Black people.

In a 1930 edition of Abbot’s Monthly magazine, an article written by Bishop W.J. Walls of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church sharply criticized the program. Noting that the characterizations were lower class, and that the dialogue was crude, repetitious, and moronic, his article spurred on publisher Robert L. Vann of the second largest African American newspaper at the time, The Pittsburgh Courier, to begin a six month long protest against the radio program. Seven hundred thousand African-Americans petitioned the Federal Radio Commission to protest the racist stereotyping of the “well-loved” Amos ‘n’ Andy.

In 1951, when the show was aired on televisions, the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored [sic] People), immediately protested. The NAACP called the show "a gross libel of the Negro and distortion of the truth." The program’s main sponsor, Blatz Brewing, also came under criticism, and withdrew their support after two years.

This circa 1930s jumpsuit from the Ivan Sayers Collection features a print from the Amos 'n’ Andy show which includes images of the Amos and Andy characters, both racialized, and the taxi cab the hapless pair drove in the radio program.

The print on this tablecloth (below) also reflects stereotypical images of Black people. To the racist eye they were watermelon-eating, music-loving, poor, and happy to be that way. It is strange to think of a white family sitting down to eat with this tablecloth, unbothered by the racist depictions underneath their plates.

Black Heroism

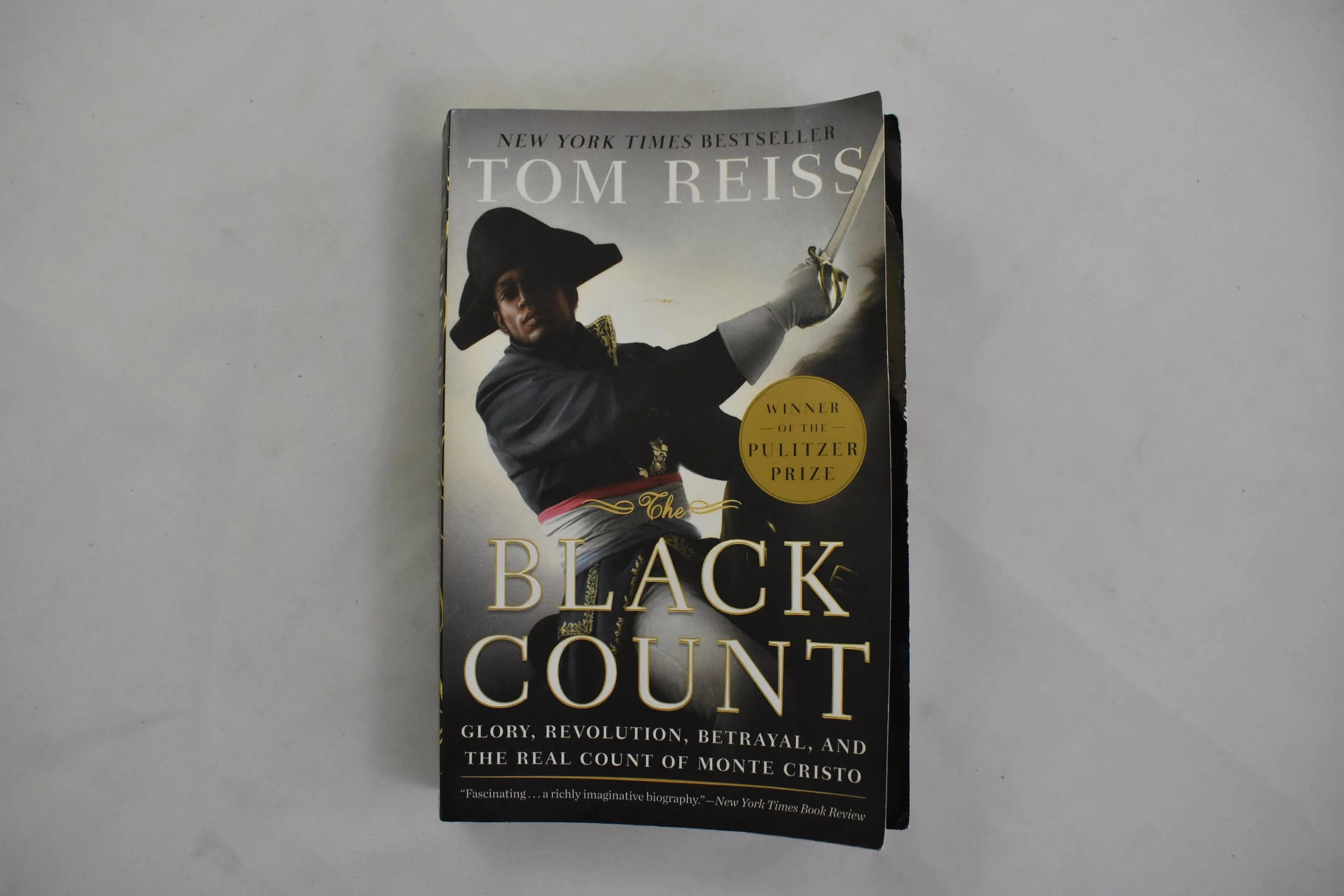

The Black Count, by Tom Reiss, tells the story of Alexandre Dumas’s father who was born to a slave in Haiti, moved to Paris, and became a respected military commander during the French Revolution.

This Airforce uniform, and the great coat with the Barbados insignia, belonged to Eustace W. Heath, Coquitlam. He was born in Barbados, and was working in Trinidad when he volunteered with the RAF. He did Air Corp Officer training in Moncton, New Brunswick, #1 Learning Pool, and was a 2nd grade pilot in the Airforce. He later completed elementary and senior flying training. He did not see active combat, but instead served as a training officer for glider pilots.

The Caribbean Air Crew website lists him as follows: 605749 – E.W. Heath – Trinidad – attested 1.12.43 – Sgt. Pilot #217 SFTS

Local research failed to turn up any current information about Mr. Heath.

SERGEANT C.A. JOSEPH AND A.O. WEEKES POSING WITH THEIR SPITFIRE MKV

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, PHOTOGRAPH CH11478, IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM COLLECTIONS.

During World War II, many men from what was then called “The British West Indies” served in the RAF. The government, during both World Wars, had exclusionary policies in place. Black men who joined the forces were generally only able to enlist in specific trades, such as cooks and stewards and in construction. The RAF was one of the first areas of Canada’s military to include Black men. Pictured here are members of the Bombay Squadron that was involved in sorties over enemy-occupied territory. Left is A.O. Weekes of Barbados, and right is Flight Sergeant C.A. Joseph of San Fernando, Trinidad. Did they know Mr. Heath?

NO.2 CONSTRUCTION BATTALION

SOURCE: NOVA SCOTIA ARCHIVES,24125654144, WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The all Black No.2 Construction Battalion was formed in 1916. They spent much of their time digging trenches at the various fronts. However, even though they were technically restricted from other positions, approximately 2000 Black Canadian men fought in the Canadian Expeditionary Force as infantrymen.

A hero of Vimy Ridge, Jeremiah Jones was recommended for the Distinguished Conduct Medal. Born in 1858, “Jerry” was 58 when he enlisted. He was also badly wounded at the Battle of Passchendaele, and was shipped home. He did not live to see the medal, which was awarded posthumously.

JEREMIAH “JERRY” ALVIN JONES, CIRCA 1917

SOURCE: PERSONAL COLLECTION OF THE JONES FAMILY, WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

VICTORIA PIONEER RIFLE CORPS, ALSO KNOWN AT THE TIME AS SIR JAMES DOUGLAS' COLOURED REGIMENT

SOURCE: IMAGE C-06124, COURTESY OF THE ROYAL BC MUSEUM

These men were by no means the first to challenge Canada’s military colour bar. Captain Runchey’s Company of Coloured Men was one of Canada’s first Black regiments and fought in the War of 1812.

In 1860-61, just before the American Civil War, the Victoria Pioneer Rifle Corps formed and volunteered their services to Governor Douglas. Largely funded by the Black community itself, they received little support from the government. Sadly, none of the Corp were invited to the farewell dinner held for Governor Douglas. By 1865 they disbanded, disheartened by their treatment.

BILLY WHIMS, SON OF GEORGE WHIMS, IN HIS WWII UNIFORM, SALT SPRING ISLAND CIRCA 1940. SOURCE: SALT SPRING ISLAND ARCHIVES, 2004032038 WHIMS, SAMPSON, WOOD, MARCOTTE PHOTO COLLECTION.

ROBERT WOOD, SENIOR, WEARING THE UNIFORM OF THE WARTIME HOME GUARD, SALT SPRING ISLAND, CIRCA 1940 SOURCE: SALT SPRING ISLAND ARCHIVES, 2004032034, WHIMS, SAMPSON, WOOD, MARCOTTE PHOTO COLLECTION

HARRY WHIMS, SON OF ROBERT WHIMS, IN WWII UNIFORM, CIRCA 1940. SOURCE: SALT SPRING ISLAND ARCHIVES, 2004032035, WHIMS, SAMPSON, WOOD, MARCOTTE PHOTO COLLECTION

Black Settlers in BC

Among the unsung and unidentified pioneers in our Black Communities were quite a few whose names and achievements have been preserved.

Many of these came in connection to specific events and settled in specific areas.

Lower Mainland and Vancouver Island

The first large influx of Black people who came to British Columbia were, to a large extent, part of a settlement scheme begun by Sir James Douglas, HBC Chief Factor and Governor of the Colony of British Columbia in 1858.

Under his factorship, the Hudson Bay Company was guaranteed proprietary rights to Vancouver Island. But there was a catch. In order to hold on to those rights, Douglas was required to establish a substantial British settlement within five years. An additional snag was the discovery of gold along the Fraser River. Gold seekers from the United States were an American influx that Douglas feared would undermine the British presence.

In 1858, Governor Douglas contacted Jeremiah Nagle, captain of The Commodore steamship that made regular trips between Victoria and San Francisco. Jeremiah took word of opportunities in Victoria to a group known as the Pioneer Committee. This group had formed in 1852 to assist the San Francisco Black population deal with prejudice and the injustices that came with it. They met regularly at the San Francisco First African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, which is where Jeremiah Nagle brought them news of opportunity in the north. Thirty-five Black members travelled to Victoria in April of that year and met with James Douglas.

On offer was the chance to purchase land at the high rate of five dollars per acre, the right of landholders to vote and sit on juries after nine months’ residence, the right to protection from the law, and the chance to become British subjects after seven years residence here.

Having fled racism in the Southern US and having been discouraged by continued racism in California, the offer was appealing. The Pioneer Committee sent a delegation to check out the situation in British Columbia. They were pleased with what they saw and many sold businesses, homes, rounded up livestock, and moved north.

GOVERNOR SIR JAMES DOUGLAS

SOURCE: ITEM # D03909, COURTESY OF THE ROYAL BC MUSEUM

PAINTING OF JEREMIAH NAGLE’S VESSEL, THE COMMODORE, ARRIVING IN VICTORIA IN 1858 WITH 400 GOLD SEEKERS.

PAINTED BY VANCOUVER ARTIST ROBERT JOHN BANKS, 1923 - 2009. ITEM#PDP00476, COURTESY OF THE ROYAL BC MUSEUM.

Victoria, Vancouver Island, and Salt Spring Island

There is considerable information available on the pioneers that came from California. Many were well-educated and continued to contribute to their new communities, as they had done in the United States. Among them were business people, teachers, farmers, and labourers. They settled in Victoria, other parts of Vancouver Island, and Salt Spring Island. Some continued on to the gold fields of the Fraser River.

Mifflin Wistar Gibbs

Mifflin Wistar Gibbs was born in Philadelphia in 1823. His father died when he was eight and, as a result, he began working at a young age to help his mother with raising four children. He learned the carpentry trade in his teens, and independently pursued his own education through voracious reading. While going on the lecture circuit with well-known abolitionist Frederick Douglass, he learned of the 1849 Gold Rush in California, and headed west where he opened a shoe and boot store with a partner, Peter Lester. While attending the Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in San Francisco, he learned of the opportunities offered by Governor James Douglas, and travelled up the coast to British Columbia in 1857. He remained in Victoria until 1870, at which point he returned to the United States where he lived to the age of 92.

Mifflin Wistar Gibbs’ accomplishments, in spite of racist roadblocks and limited opportunities, are both numerous and impressive, as can be seen in the following list:

Member of the Philadelphia Library Company, devoted to discussion of social and legal issues facing Blacks in the United States

Business owner, “Lester & Gibbs, Importers of Fine Boots and Shoes from Philadelphia, London and Paris”

Founded first Black newspaper in San Francisco, The Mirror of the Times

Property Owner

Member of the Victoria City Council, 1866, representing the James Bay District

Salt Spring Island delegate at the Yale Convention, 1868, to debate the fate of British Columbia as either part of Canada or annexation to the United States

Director and major shareholder in the Queen Charlotte Coal Company

Won bid to construct a wharf and tramway for the Queen Charlotte Coal Company

Author, Shadows and Light, autobiography published in 1902

Served as a judge in Little Rock Arkansas

Served as State Registrar of Lands under President Harrison

Held the position of United States Consul to Madagascar

These he achieved in the face of the following setbacks and hurdles:

In California, Blacks were not allowed to testify in court against white people.

Schools for Blacks in California did not go beyond elementary level.

Businessmen such as Mifflin Gibbs paid a business tax known as a “poll tax,” the tax paid by voters, but were denied the vote. In an effort to end this discrimination, Gibbs and his partner, Peter Lester, refused to pay the tax. The government then seized their property, equivalent to the tax. These goods were put up for auction, but an informed crowd refused to bid. This protest did not end the poll tax, but payments from Black citizens were rarely enforced after this.

Though married with children and very successful, the prejudice of white people in the same economic class made his wife, Maria Anne Alexander, a graduate of Oberlin College, return to the United States.

Recognized on his merits by many whites in British Columbia, he nonetheless experienced racism. For example, while attending a concert in Victoria he was doused with flour, and in spite of his support for Governor Douglas, he was not admitted to a farewell banquet for Douglas. These petty persecutions were echoed by more insidious examples of prejudice. Various people attempted to thwart Gibbs in political life by using race as a way to limit his success.

SOURCE: ITEM #A-01627, COURTESY OF ROYAL BC MUSEUM

SOURCE: ITEM # A01626, COURTESY ROYAL BC MUSEUM

Peter and Nancy Lester

Peter Lester was the business partner of Mifflin Gibbs, both in San Francisco and in Victoria. A boot maker by trade, his expertise helped make the Lester and Gibbs, Importers of Fine Shoes business a success.

Like his business partner, Mifflin Gibbs, Peter Lester and his family became strong members of their Victoria community. Some of their accomplishments are listed below, followed by another unfortunate list of setbacks:

Successes

Business owner of Emporium for Fine Boots and Shoes, imported from Philadelphia, London and Paris.

After moving to California and finding that slavery still existed there, he helped educate slaves and domestic workers on their rights.

Was first Black juror in Victoria, in 1860, twelve years before this was formally allowed.

Owner of at least 10 properties.

The Lesters’ three children, Sarah, Peter, and Frederick were contributing citizens of Victoria. Sarah taught piano, Peter was a painter, and Frederick was a carpenter.

Both a Peter and a Frederick D. Lester appear in the British Columbia Department of Lands and Works records between 1871 -1908.

Setbacks

Assaulted by two white men who then stole a pair of shoes in his store in San Francisco, Peter Lester was left with no legal recourse. Blacks were not allowed to testify in court.

The pro-slavery newspaper, The San Francisco Herald, demanded the removal of his 15-year-old daughter from a white school. Despite protests, she was eventually forced to leave the school.

Salt Spring Island and Surrounding Areas

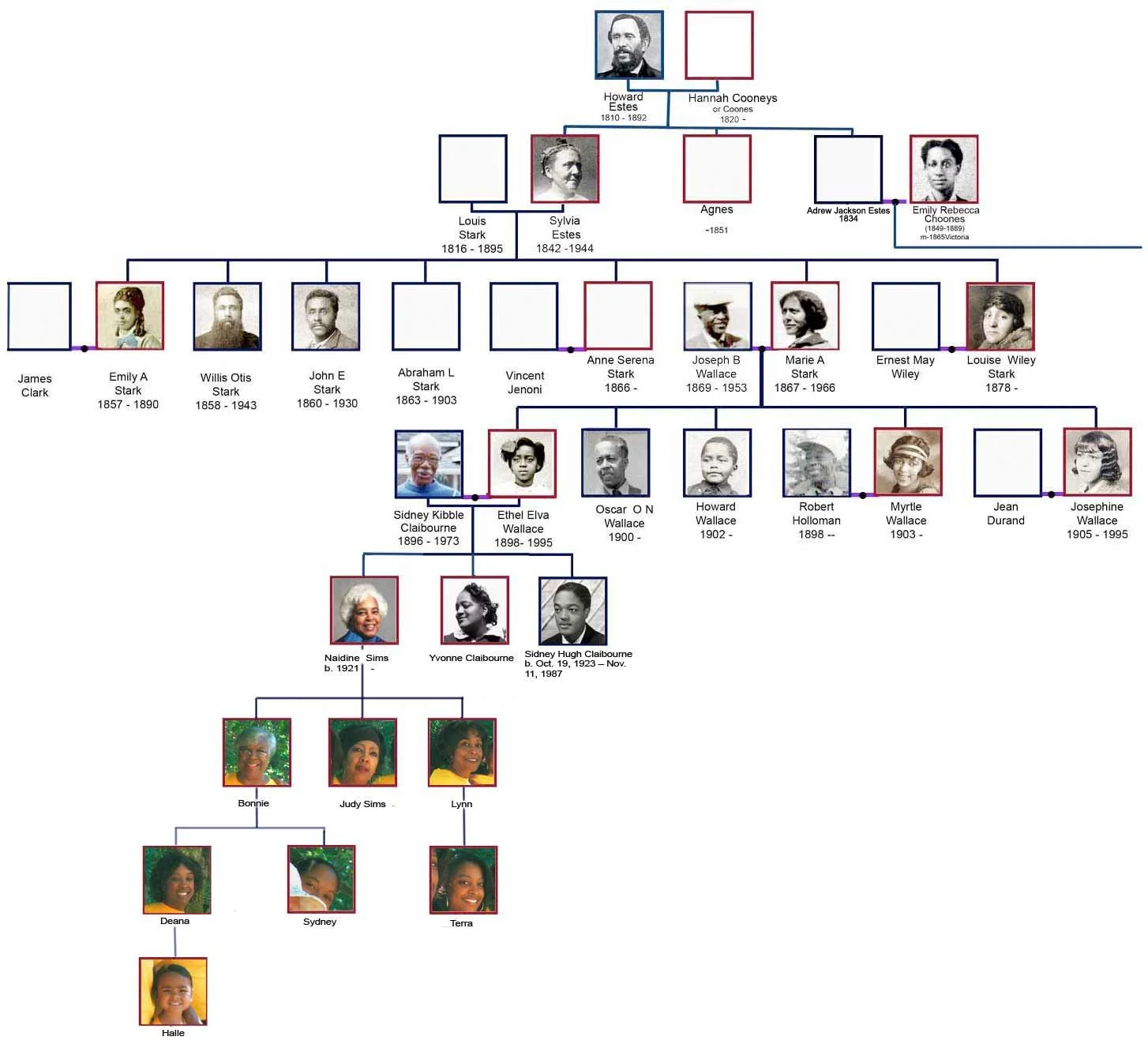

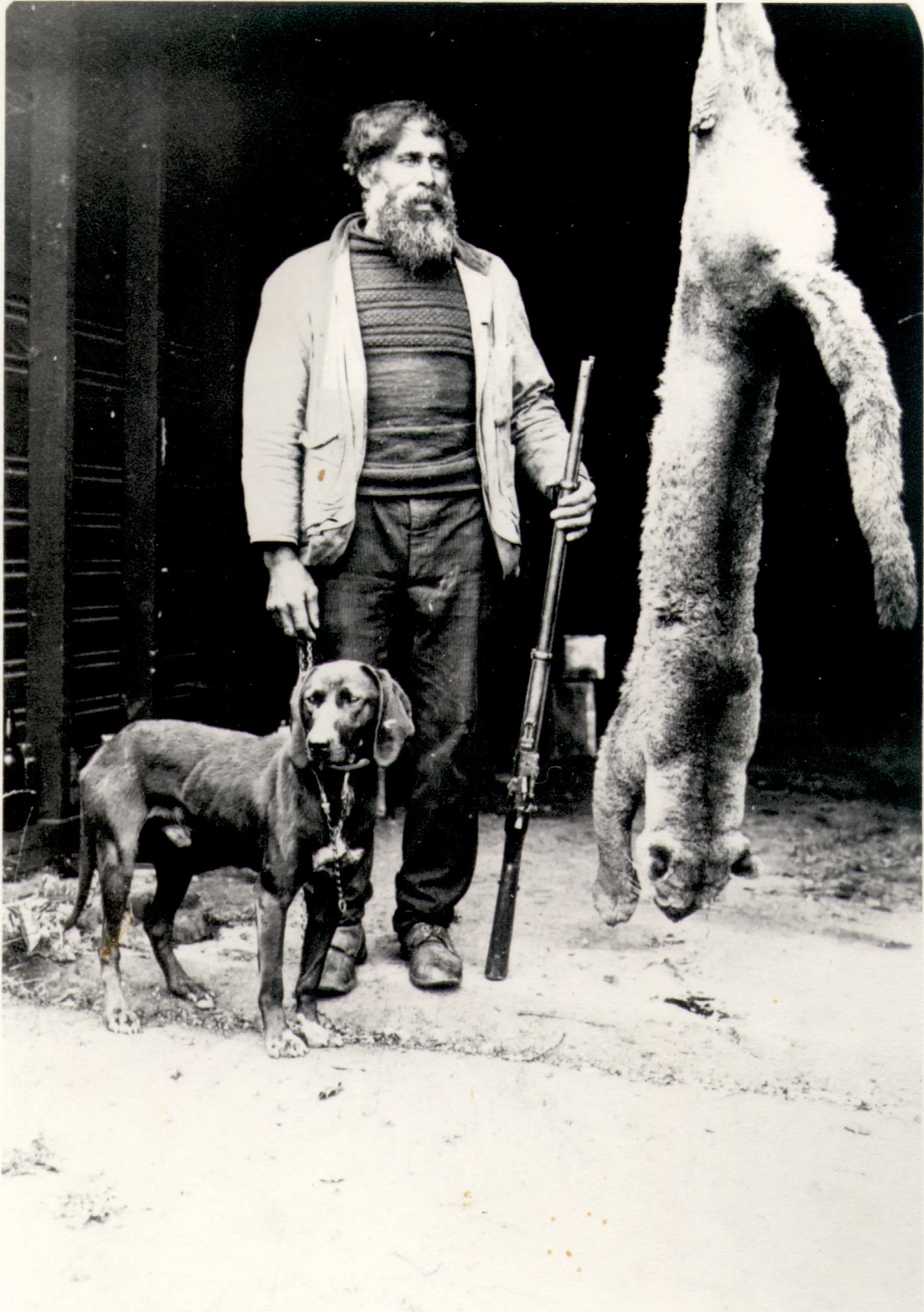

Some of the settlers who left California for Victoria eventually made their way to Salt Spring Island. Some of the families that settled there included the Buckners, Copelands, Harrisons, Robinsons, Estes, Whims, Jones, Isaacs, Levis, Curtis, Wall, Sampson, and others. Most of these settlers faced hardships typical of the time. They cut places to live from the bush, sometimes hunted for food, planted gardens, preserved foods for winter, and lived without the modern conveniences we take for granted. Though this exhibit cannot possibly do justice to the many experiences these people lived through, even if they had been recorded in detail, one family’s history is fairly well-known, and likely shared some similarities with the others.

The Stark Family

Louis and Sylvia (nee Estes) Stark came from California in the 1880s, looking for a better life. This married couple arrived in British Columbia with two children, Emma and Willis, then had Marie, Emily, John, Abraham, Anne,

and Louise.

Sylvia’s family came from Clay County, Missouri and had the surname of their owner, Tom Estes. Sylvia’s father Howard first went to California on Tom Estes’ orders, driving cattle across the country with Tom Estes' sons to supply the 1949 gold miners. Part of the deal was that Howard would be given the opportunity to earn money there to buy his freedom. Tom Estes reneged on his part of the deal. Howard paid Tom Estes $1000 twice to buy his freedom and was only given it after another $800 was paid and a court ordered Estes to free Howard and his family.

Howard subsequently brought the rest of his family to California, a perilous overland journey in those days. The Estes family settled in California for a time, during which Sylvia married Louis Stark, her father’s partner. When the chance came to find freedom in British Columbia in 1858, the Estes made the trip, followed by Louis Stark and his cattle. After some time in Victoria, the Estes family settled in Saanich, while Louis Stark, his wife Sylvia, and others made their way to Salt Spring Island and made their homes in the wilderness. Some of them, and their descendants, are pictured here.

They had many difficulties and adventures dealing with the Indigenous people, wildlife, and other things in the area, but Sylvia found comfort in her faith allowing her to raise her family in these new circumstances. Willis grew up on Salt Spring Island and became known as “the panther” due to his cougar hunting skill. John became a prospector and mineralogist. Emma became the first teacher at Cedar, south of Nanaimo, in 1874.

SYLVIA STARK LIVED A LONG LIFE FULL OF CHANGES, TRIALS, AND ADVENTURES. SHE IS PICTURED HERE IN THE 1940S.

SALT SPRING ISLAND ARCHIVES, ESTES-STARK COLLECTION, 989024038

The document to left has been transcribed below.

Know all men by these presents that I Howard Estes of the County of Clay in the State of Missouri have manumitted and set free and by these presets so manumit emancipate and set free from slavery or servitude certain slaves belonging to me. To wit Hannah a light colored black woman aged about 48 years Jackson a light colored black boy aged about 16 years and Sylvia a light colored black girl aged about 12 years and I do hereby give grant and release unto the said Howard Jackson and Cynthia all my right […] claim of in and to their personal services and labor and of in and to the Estates and property which they may hereafter acquire or which they may have heretofore acquired hereby releasing and forever freeing them from all claim that I may have had to their personal labor and services and by these presents do declare them free both from me and my heirs forever. In Testimony whereof I the said Howard Estes have hereunto subscribed my name and affixed my seal this the tenth day of November in the year of our Lord one thousand Eight hundred and fifty two.

Howard X Estes

State of Missouri […] in the Council Court of Clay County in the State of Missouri

County of Clay November the 17th AD 1852Be it remembered that Howard Estes a man of colour this day appeared in open court and Simpson McGaughey) and Charles I. L. Leopold two […] Witnesses having been duly sworn in open court deposeth and saith that the said Howard Estes is the person whose name is subscribed to a Deed of Emancipation To Hannah aged about forty eight years Jackson about sixteen years old Sylvia about twelve years old as a party thereto and the said Howard Estes then and there acknowledged the fact that he executed and delivered the said instrument of […] civic […] or Deed of Emancipation as his voluntary act and deed for the uses and purposes therein mentioned and the black is ordered to certify thee same accordingly

In Testimony whereof I Samuel Tilley Clerk of the Circuit Court within and for the County of Clay in the State of Missouri have hereunto subscribed my name and offered the seal of said Court at office in the city of Liberty in the County of Clay and State of Missouri this day of November AD

1852

Samuel Tilley ClerkMem filed the 17th Nov. AD 1852

John Craven Jones

Another notable settler on Salt Spring Island was John Craven Jones. John came to Salt Spring Island in 1859, along with his two brothers William Allen Jones and Elias Toussaint Jones. All three brothers were graduates of Oberlin College, and after graduating John was principal at the Black Xenia School in Ohio. Arriving on Salt Spring Island when he was 25, and discovering there was no school, he took it upon himself to teach the settlers’ children wherever he could; sometimes in sheds or in peoples’ homes. A log school house was finally built in 1865, where Central School was located. John would teach there three days a week, then go to the north of the island and teach there for three days. Because of the prevalence of wildlife, especially cougars, people did not want their children travelling to either school.

John met Almira Scott on a visit to Ohio. She was a fellow graduate of Oberlin College, and a widow with three children. They married in 1882.

An old 1872 school report recorded that, "The schoolmaster offered his charges instruction in Latin, philosophy and human rights education that was the envy of the wealthiest white citizens in nearby Victoria and the mainland."

All this and, between 1859 to 1869, without pay. He received goods for services for a decade until the Salt Spring Island School District was created, at which point he was paid $40 per month until he retired and returned to Ohio in 1875.

The Salt Spring Island Archives has a wealth of information about some of the families that settled that area, including details about the Stark and Estes families’ experiences.

Outlying Areas

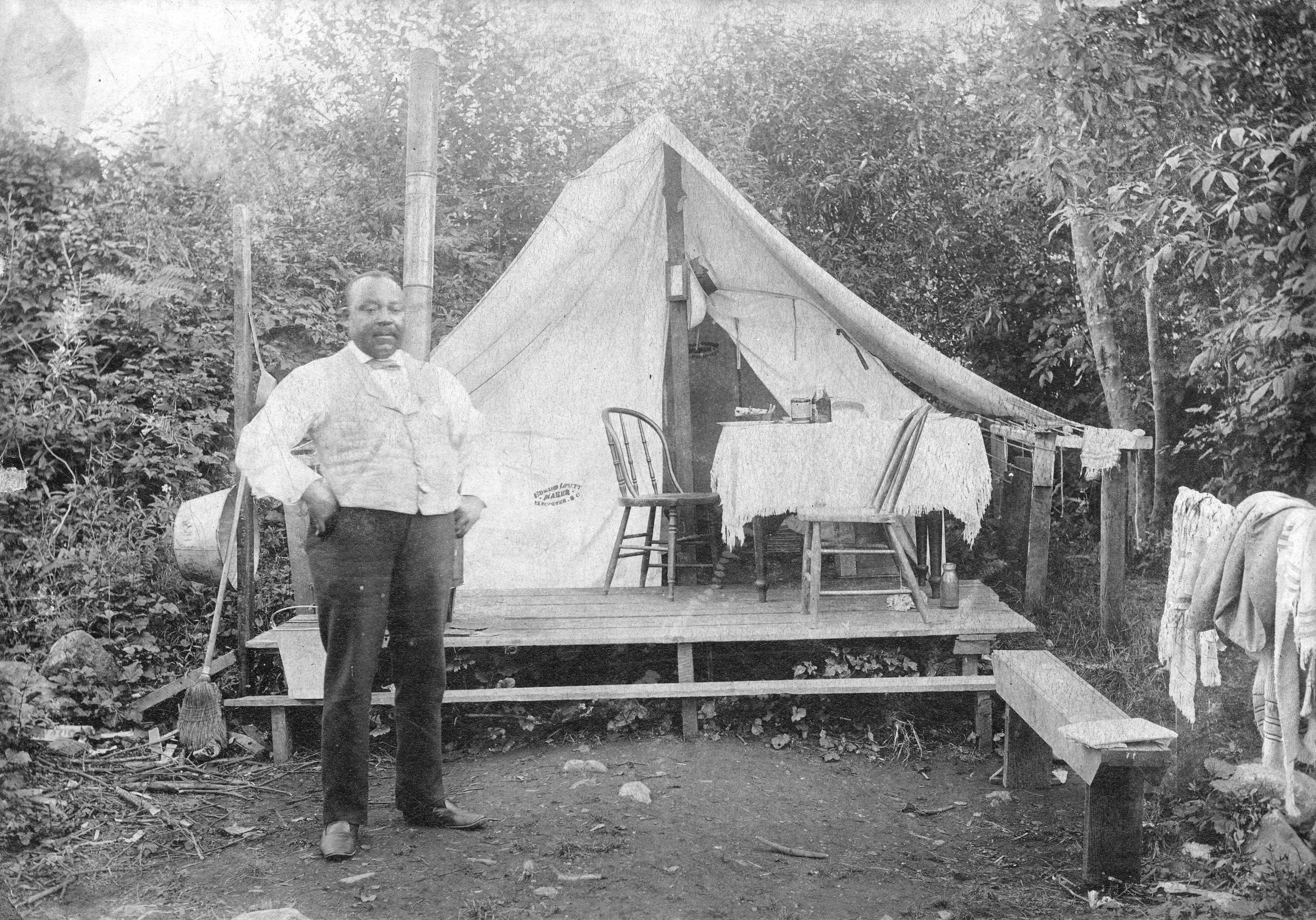

THIS IS AN IMAGE OF BURTON ISOM, CIRCA LATE 1800S, A MAN IDENTIFIED AS HAVING MINED IN THE BARKERVILLE AREA. HE WAS BORN IN MISSOULA COUNTY, MONTANA IN 1833, AND DIED IN 1906. HE WAS BURIED IN THE OLD MAN’S PROVINCIAL CEMETERY, KAMLOOPS. HIS NAME APPEARS IN A CENSUS FROM NANAIMO AND NOONAS BAY, BC, WHERE HE IS LISTED AS BEING 41 AND METHODIST. HE IS ALSO SHOWN TO HAVE HELD MINERS’ LICENSES REGISTERED IN RICHFIELD (BARKERVILLE) EVERY YEAR 1862 TO 1870.

SOURCE: ITEM # 1999.0009.0001.171, TREGILLUS, BARKERVILLE ARCHIVES

A number of the Black people that came to BC from California didn’t stay long in Victoria. Of these, many followed the lure of the gold rush, travelling beyond the Lower Mainland, and there are a number of places in the province that are named for some of these people.

William Allen Jones, John Craven Jones’ brother, was one of them. He was the first dentist to be granted a license to practice dentistry in British Columbia. He achieved this in 1886. Already educated at Oberlin College in Ohio, he arrived in BC and initially settled on Salt Spring Island. His other brother, Elias, prospected in the Cariboo gold fields for a couple of years before returning to the United States, and William Allen went to Barkerville where he set up shop as the town’s dentist. He was known as “Painless Jones.” Though he returned to the United States after the Civil War to continue his dental studies, he made his way back to Barkerville and lived there until he died of pneumonia in 1897.

A very small article in the morning edition of the Victoria Daily Colonist, December 4, 1872 mentions both Burton Isom, and John Richard Giscome, who may have been one and the same as John Robert Giscome (see below).

The article states:

“NOTICE

A judgement against John Richard Giscome in favour of Burton Isom, for $35 and costs, has been registered in the Land Registry Office as a charge upon the real estate of John Richard Giscome. -- J. Roland Hett, Solicitor, Bastion St.”

Other Black people who lived in Barkerville, at one time or another, are mentioned in the book Barkerville: Williams Creek, Cariboo by Richard Thomas Wright. John Anderson was the Cariboo correspondent for the San Francisco Black community newspaper, the Elevator. Johnny McLean, born in Barbados, was the caretaker for the Richfield courthouse. He also partnered with John Giscome and Henry McDame (see below). Another man, David Lewis, originally from Columbus, Ohio, was a dentist and a barber. He died in Barkerville, aged 60. Rebecca Gibbs was a laundress and may have been married to one of Mifflin Gibb’s brothers. She also wrote poetry and had three poems published in the “Cariboo Central. These people are documented, but there were many who have left no traces.

John Robert Giscome

John Robert Giscome was born in Jamaica and left home with his brother, at 22, to work on a Panama railway. After this he travelled to the California goldfields, then to Victoria with the pioneers of 1857. From Victoria he travelled to Quesnel where he teamed up with Henry McDame, from Barbados. On their way to the Peace River country, weather conditions forced them to try an overland route, previously only travelled by the native tribes in the area. On the way they discovered the remains of the Rennie party who had tried to reach Barkerville. Giscome reported his find, then returned to bury them.

Giscome and McDame had little success in the Cariboo, but in 1870 were finally successful prospecting during the Onimeca Gold Rush. Four years later, McDame found gold in a tributary of the Dease River and McDame, Giscome, and some others started the Discovery Company. British Columbia’s largest gold nugget was found on this claim in 1877. Weighing in at 72 Troy ounces (2.24kg), it was the size of a potato.

Giscome retired to Victoria and invested in property. When he died in 1907, he bequeathed $21,000 to his landlady.

Giscome’s history lives on in the names of Giscome Portage Trail and Giscome Rapids. McDame Creek, near Cassiar, is named for Henry McDame.

THE S.S. CHILCO TAKES ON WOOD AT THE GISCOME RAPIDS, 1910. PHOTO BY FRANK CYRIL SWANNELL, 1880 - 1969

SOURCE: ITEM I-59652 COURTESY OF THE ROYAL BC MUSEUM

GISCOME SAWMILL IN 1917. PHOTO BY FRANK CYRIL SWANNELL, 1880 - 1969.

SOURCE: ITEM F-0433, COURTESY OF THE ROYAL BC MUSEUM

Arthur Lee Clore

Arthur Clore was born in Culpepper, Virginia, 1887, and died in 1968 in Terrace, BC. His father served in a Black regiment during the American Civil War. Records show that Arthur and a man named George Little staked a claim north east of Terrace, on Kleanza Mountain in 1925, then in 1935 the pair staked another claim there, higher up, called the Beanstock Claim. It seems that he eventually made his way to Alaska where he is listed both as a farmer and, as late as 1939, as a prospector. Clore River and Mount Clore, southwest of Terrace, are named after this man.

The Royal British Columbia Museum has a copy of a CBC interview with Arthur Clore when he was an older man. In the interview, Arthur recalls some of the people and events that took place in the Skeena River, Alaska, the Copper River and Kitselas areas, circa 1910. He speaks about some of the old-timers that lived there at the end of the 1800s, including Charlie Kendle who was in the US Army when they were chasing Sitting Bull, and who was “tough as rawhide.” Another old-timer, named Kerr, had been in the thick of the Riel Rebellion. He describes the ruins of large Haida villages on islands in the Skeena River, and charcoal remains from ancient Indigenous groups. He crossed the Skeena River on a basket ferry, walked the trails from one settlement to another, and dealt with clouds of mosquitoes. “The sun looked green through their wings,” he chuckles in the interview. He recalls a steamboat that capsized with a safe filled with $30,000 coming from the Hudson’s Bay Company, and the year the summer sky was red for months after a huge volcanic eruption in Alaska (likely the “Novarupta,” several magnitudes larger than Mount St. Helen’s), and sighting Haley’s Comet in 1910 when he was in Alaska where the sun was up all night long. At that time, Arthur says, Smithers was just a swamp and people were cheerful, hopeful, polite, good-natured, and good-humoured.

MAIN ST. KITSELAS, CIRCA 1910. THIS SCENE WOULD HAVE BEEN ONE THAT ARTHUR CLORE WOULD HAVE BEEN VERY FAMILIAR WITH. SOURCE: ITEM #E-00050, COURTESY OF THE ROYAL BC MUSEUM

STEAMBOATS AT KITSELAS, 1911. SOURCE: ITEM # C-05485, COURTESY OF THE ROYAL BC MUSEUM

Grafton Tyler Brown

Grafton Tyler Brown was born in 1841. His parents were freed Black slaves who had moved from Maryland to the free state of Pennsylvania. Brown went to California in 1861, where he learned painting and lithography from a German artist. After his German mentor and employer died, Grafton took the lead in lithography printing on the Pacific Coast, printing the labels for John Deas’ cannery, among other things. In 1882 he moved to British Columbia where he joined a survey party. While travelling through the province he made sketches that he later turned into paintings. Though he moved back to the United States after a few years, it was in BC that he began his career as a professional artist.

Deas Island

A Black man named John Sullivan Deas, born in 1838, was once the leading salmon canner on the Fraser River. He came to Canada around 1862. A tinsmith by trade, he started canning salmon on the lower Fraser River in 1871. As rival canneries began operating, Deas noted that the salmon fishing on the Fraser River had fewer fish and a shorter season than the Columbia and requested an exclusive lease on drifts near his cannery on the Fraser. His request was denied and, shortly after, Deas and his family sold the business and moved to Seattle.

Though a highly successful businessman, he and his family were written about in an issue of the Victoria Colonist newspaper. The article spoke about a house the Deas family lived in with their seven children as being haunted, creating a false notion of Blacks as superstitious and objects of amusement. Deas was also sometimes mentioned, in relation to his business, as just one of the workers, not the owner of his business. In addition to this, in an attempt to stop a rival company from encroaching on his drifts, Deas was accused of using threatening language. Deas was sentenced to three weeks in prison, but met his bail and the case was eventually dismissed as an attempt to interfere in Deas’ business.

Deas Island is named after John Sullivan Deas.

THIS LABEL WAS PRINTED BY THE ARTIST GRAFTON TYLER BROWN, ANOTHER CALIFORNIA BLACK MAN WHO SPENT TIME IN BRITISH COLUMBIA. SOURCE: ITEM I-61596, COURTESY OF THE ROYAL BC MUSEUM

A DEAS ISLAND CANNERY, CIRCA 1892, MANY YEARS AFTER JOHN DEAS HAD LEFT THE REGION. SOURCE: ITEM D-05348, COURTESY OF THE ROYAL BC MUSEUM

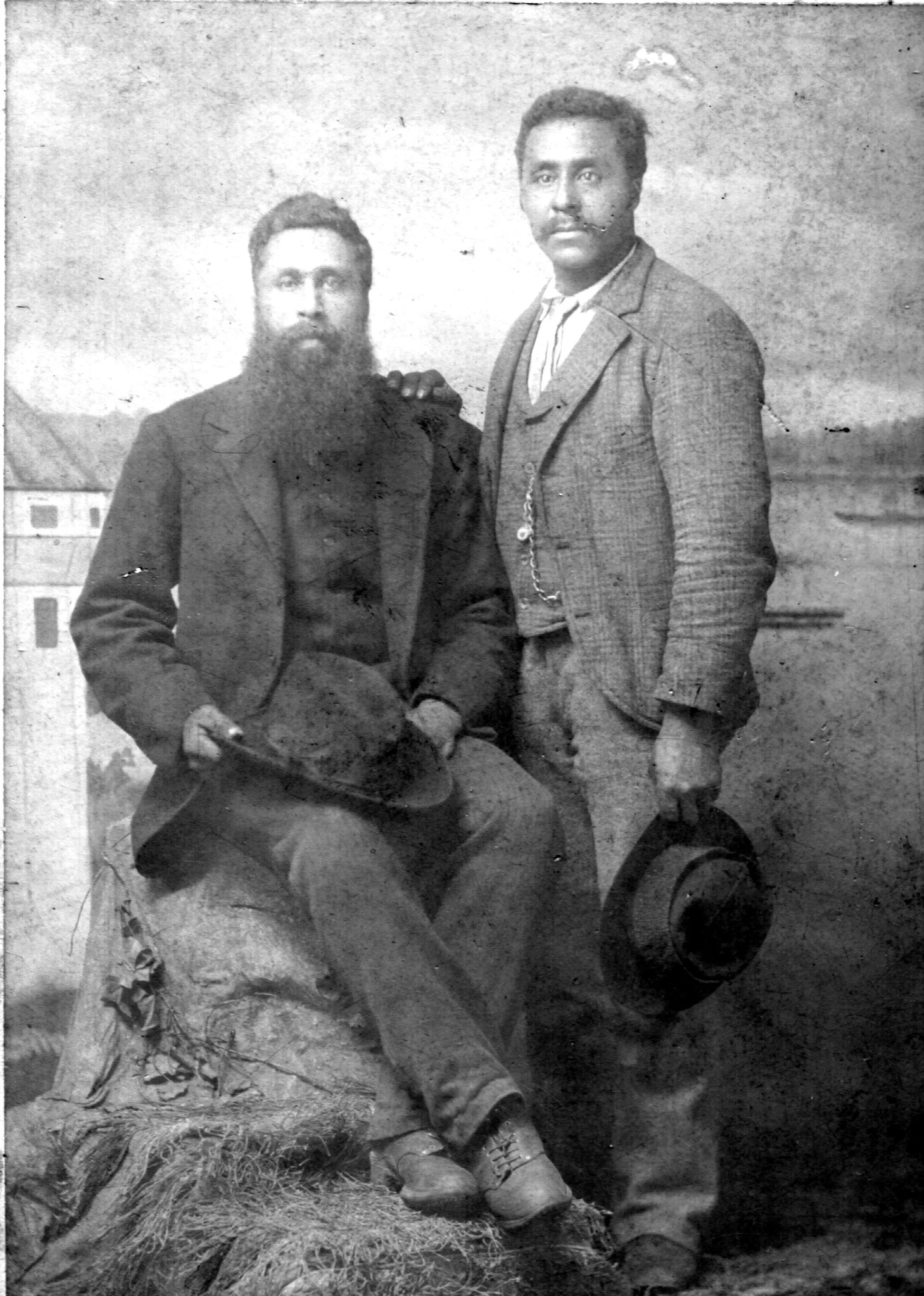

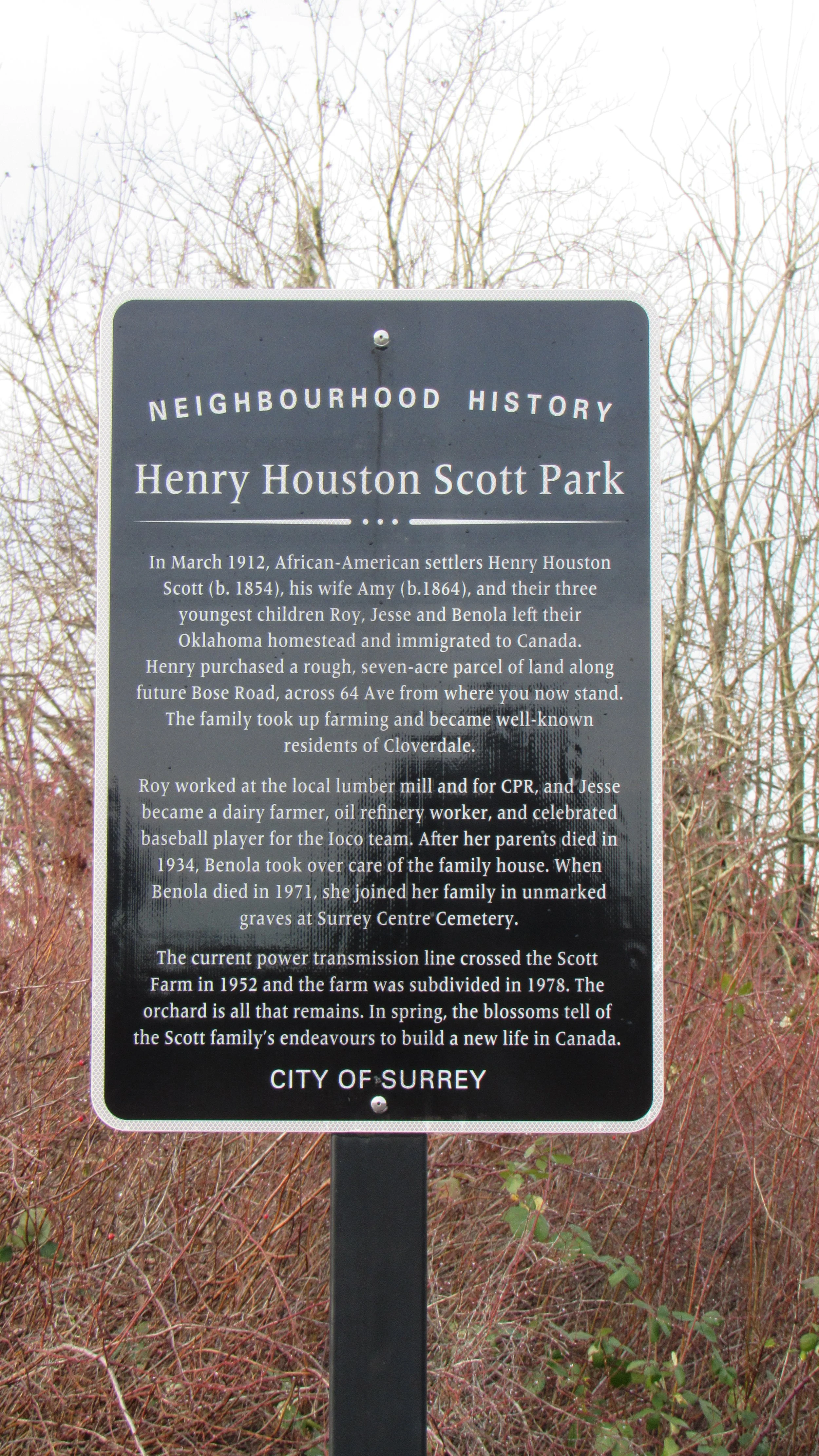

Henry Houston Scott

Born in Texas, 1854, ten years before the abolishment of slavery in the United States, Henry Houston Scott met his wife, Amy Florence Alridge, in Mississipi. In 1905, the couple homesteaded in Oklahoma. Seven years later they moved to British Columbia, settling in what is now Surrey where they grew hay and kept dairy cattle.

Records suggest that the Scotts had ten children, but only three of them came to Canada with Henry and Amy. The three children that came with them were Jesse, Roy, and Benola Myrtle. Roy, the oldest, worked at a lumber mill, and also as a railway porter. Next in line was Jesse. Jesse continued to work on the family farm, but was also a baseball player. He played for the IOCO (Imperial Oil Company) senior baseball team. The youngest, Benola Myrtle, became a singer of some note.

IOCO Baseball Team

IOCO Senior Baseball Team, 1923. Jesse played outfield and is standing behind the bat boy. Other members of the team were Jack Bacon, B. Cameron, R. Cameron, W. Clark, Coyle, Craig, P. Dowding, Dean Freshfield, P. Robinson, and P. Thorburn.

SOURCE: PORT MOODY STATION MUSEUM, ACC. # 2000.018.001

Hogan’s Alley and Old Strathcona

Old Strathcona and Hogan’s Alley are a part of Vancouver that once held a thriving Black Community. Thanks to the work of many organizations, notably the African Descent Society British Columbia, the Hogan’s Alley Society, and Black Strathcona, much of the history of this community has been researched and preserved. Despite their relative prominence in Vancouver’s history, many people know very little or nothing about these communities. The community, as a cohesive group, ceased to exist in the 1970s, and it is only recently that work has been done to preserve the stories that tell of a specific time and place in Lower Mainland history. The following pictures are of some of the early residents of this area.

Joe Fortes

Joe supported himself with odd jobs, and during the summer months lived in a tent at English Bay where he acted as a self-appointed, unpaid lifeguard in his free time. In 1900, he became the city’s first officially appointed lifeguard. He is credited with saving many lives, and in 1910 the city honoured him with a gold watch, a cheque, and an illuminated address in recognition of his service to the public.

He died in 1922 and his flat gravestone at Mountainview Cemetery reads only “JOE.” In 1986, the Vancouver Historical Society named him “Citizen of the Century.” His name lives on at the Joe Fortes Branch of the Vancouver Public Library, and the Joe Fortes Fountain, located at 1755 Beach Avenue, Vancouver.

Link to the NFB short film “Joe” that tells the story of Seraphim “Joe” Fortes. Playing: Black Communities in Canada: A Rich History (nfb.ca)

Hogan’s Alley

Hogan’s Alley was actually Park Lane, and it ran between Union and Prior streets, from Main Street to Jackson Avenue, located in the Strathcona neighbourhood. Some of the families that lived there were descendants of the Blacks who came to Victoria in 1858. Some came from Oklahoma by way of Alberta, and some from the West Indies. Many Black men in Canada found reasonable employment as porters on the trains, making the area a handy place to live. The area became a thriving Black community with restaurants, a church, and schools. Being close to the railway station and a hive of activity, also meant that Black Strathcona was a go-to destination for many famous people performing in Vancouver.

Unfortunately, the city began making life difficult for the citizens of Black Strathcona, rezoning the area to impede home improvements or the ability to get mortgages. In the 1950s and 60s, the city stopped maintaining roads and sidewalks in the area. They began to portray the area as a run-down, slum-like place. The city also planned a freeway at this time that would run through Strathcona and Chinatown. The freeway was never completed but in 1971 the first phase, the Georgia Viaduct, was built and two blocks of homes on Hogan’s Alley were razed, and surrounding businesses began to suffer. It was the death knell for the community. Most residents eventually left the area, and all that remains are the stories, images, and street names.

FOUNTAIN CHAPEL WAS PURCHASED BY THE STRATHCONA NEIGHBOURHOOD IN A FUND-RAISING CAMPAIGN LED BY NORA HENDERSON, JIMI HENDRIX’S GRANDMOTHER. AFTER SECURING $500 FROM THE AMERICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH TOWARD A CHURCH OF THEIR OWN, THE REST OF THE FUNDS WERE RAISED BY THE COMMUNITY THROUGH BAZAARS, SUPPERS, AND OTHER ENTERTAINMENT. THE FOUNTAIN CHAPEL, ALSO KNOWN AS THE AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH, CHANGED HANDS IN 1969 BECOMING THE CRY IN THE WILDERNESS CHURCH.

SOURCE: VANCOUVER ARCHIVES, CVA786-49.20

GEORGIA AND DUNSMUIR RAMPS OVER MAIN STREET 1971.

SOURCE: VANCOUVER ARCHIVES, CVA 216-1.23

CLOSE UP OF VIE’S CHICKEN AND STEAK HOUSE FROM THE IMAGE ABOVE

LONDON DRUGS IN BUSINESS : CITY OF VANCOUVER ARCHIVES, CVA 203-9

CLOSING SALE LONDON DRUGS, CITY OF VANCOUVER ARCHIVES, CVA 447-88

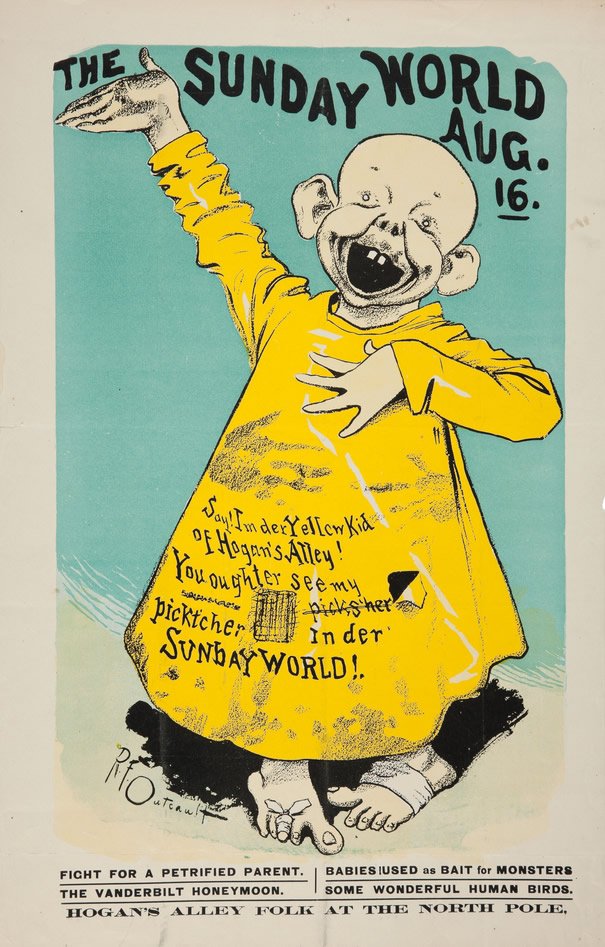

THE YELLOW KID FROM SUNDAY WORLD, AUGUST 16, 1896.

SOURCE: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The photograph to the left shows the Georgia and Dunsmuir Viaduct ramps crossing Main Street, 1971. It looks Northeast, and one of the buildings in the background is Vie’s Chicken and Steakhouse, which was located at 209 Union Street. As the picture shows, Vie’s was not destroyed by the viaduct construction, and continued to operate until 1979. After Vie’s death in 1975 the restaurant was run by her daughter, Adelene, also known as “Ma.”

Vie’s Chicken and Steak House was a hub of social life in the Hogan’s Alley Community. Many famous people came there after their performances and mingled with the patrons of Vie’s. Some of these included Lena Horne, Sammy Davis Jr, Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, Count Basie, Nat King Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Diana Ross and the Supremes, and Jimi Hendrix. Jimi Hendrix’s grandmother was a cook at Vie’s at one time.

The following excerpt from page 38 of Vancouver City Council meeting minutes discusses a dispute over a price for property purchased by the city for the building of the Georgia Viaduct.

The City Solicitor and Supervisor of Property & Insurance report as follows: "Reference is made to Item 1, Property Matters, October 16, 1970 confirmed by Council October 20, 1970, authorizing the acquisition of Lots 3, 4 & 5, Block 21, D.L. 196, being 818, 822 and 826 Main Street, for the sum of $61,000.00. This property was conveyed to the City, consolidated with adjoining parcels and now forms part of the Right-of-way for the Georgia Viaduct Replacement. The owners had claimed $90,000.00 as representing the value to the owners but after further negotiations, the owners' agent had agreed to recommend a settlement in the sum of $61,000.00 to cover all elements of claim. The owners were not prepared to accept the basis of settlement suggested by their agent, and advised that future negotiations be with their solicitor. There have been further negotiations with the solicitor, Mr. Graham C. Mackenzie of Braidwood, Nuttall, MacKenzie, Brewer & Co., and the City Solicitor. We now have a letter indicating that settlement can be accomplished for the sum of $64,000.00. The City Solicitor and the Supervisor of Property & Insurance have reviewed the independent appraisals and the owners' compensable costs, such as appraisals, legal fees, frustration of the use of the property by members of the owners' family in the conduct of their business located nearby. They have come to the conclusion that while this appears to be the maximum which could be recommended for acceptance, arbitration proceedings might very well result in a cost to the City of an amount considerably in excess thereof. RECOMMENDED that the City Solicitor and the Supervisor of Property & Insurance be authorized to settle the acquisition of the above property for the total sum of $64,000.00, chargeable to Code # l72/ll20."

Source: File F107.02, Council Meeting Minutes, June 8, 1971, City of Vancouver Archives, COV-S648-F0687

Not many know that Hogan’s Alley was the name of a fictional neighbourhood in a comic strip from New York City. The Hogan’s Alley comic strip, by Richard Felton Outcault, made fun of the large, poor Irish population of New York, and featured Mickey Dugan, aka “the Yellow Kid.” It is unclear who first nicknamed Park Lane Hogan’s Alley, but it is clear that, whoever it was, considered it to be similar to the Irish slum in the comic strip.

Much more information on the Strathcona neighbourhood, and Hogan’s Alley can be found at the following websites:

In addition, walking tours of the area are available from the

African Descent Society at:

The Second Wave: The West Indies

In the 1950s, the West Indies were still, like Canada, a member of the Commonwealth, but official policies were in place to limit non-white immigration. One of the reasons used to justify this exclusion was Canada’s racist and erroneous notion that people from the West Indies could not handle Canada’s winters. In response to protests, the government enacted the The West Indian Domestic Scheme in 1955. This allowed single women between the ages of 18 and 35 from the West Indies to come to Canada to work as “domestics” for a year, at which point they could be granted immigrant status. Approximately 2600 women came at this time, despite the fact that opportunities were limited, and working conditions were often less than ideal. Many were well-educated but relegated to positions of service, and treated accordingly. If faced with dismissal or abuse these women had little recourse. In addition to this, the policy was designed to exclude families and discourage settling. Many of the women who came under this policy felt isolated and were treated as outsiders. Most of the men who came to Canada at this time did so for education. Unless they married a Canadian, they were expected to return to the West Indies.

A CPR PORTER STANDS NEAR A WORKTABLE, AND STEAM PRESS, USED TO PRESS PORTER UNIFORMS, IN THE SLEEPING, DINING, AND PARLOUR CAR DEPT. STORAGE WAREHOUSE, VANCOUVER, 1914.

SOURCE: CITY OF VANCOUVER ARCHIVES, CVA 152-1.235

Train Porters

In the 1870s, Canada’s railways invested in sleeper cars for their trains, allowing passengers to travel in comfort. Sleeper cars, or Pullman cars, as they were known at the time, were the invention of American George Pullman, featured chandeliers, walnut panelling, seats that unfolded to become beds, silk window shades, and other luxuries. The sleeper cars became very popular, and one of the reasons for this was the employment of Black porters, held to a model of post-enslavement servitude. After the Civil War, thousands of Black people were looking for paid employment, and many men found opportunities as porters on Pullman’s trains. When Canada purchased sleeper cars, they adopted the same model of service.

Many porters were hired from places that had a settled Black population, such as Africville in Nova Scotia, Little Burgundy in Montreal, and the Bathurst and Bloor street area of Toronto. It was no accident that Hogan’s Alley in Vancouver grew around the area adjacent to the Great Northern Railway station.

Train porters were required to deliver “Pullman service.” This entailed tending to passengers’ every need. The porters were continually on call, held to a strict code of conduct, and if disputes between passengers and porters occurred, the porter was never the winner. Many were dismissed, reprimanded, or docked pay for spurious reasons such as being perceived as “too attentive” to ladies on board, for minor spills, or for not being prompt enough with service. On long trips, while passengers slept, porters stayed awake polishing passengers’ shoes and responding to calls for service.

THIS PHOTOGRAPH IS TITLED MR.COURTNEY AND BABY, AND WAS TAKEN IN EDMONTON, ALBERTA, 1925. THE PORTER WAS NOT IDENTIFIED.

SOURCE: ITEM # NC-6-11624A, GLENBOW ARCHIVES

However, the neighbourhoods where the porters congregated allowed for conversation and planning that played a part in significant changes to Canada’s racially discriminating laws. At the beginning of the 1900s, many Blacks in Canada came from the Caribbean and were well-educated. Unfortunately, because of racism and discriminatory hiring policies, they were only able to find jobs in service which for many meant working as train porters. These men were not allowed to join the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees (CBRE) union based on their skin colour. They were not allowed to move up in the ranks of railway employment, were paid lower wages, and had no job security, among other injustices.

TITLED, WOMEN ATHLETES LEAVING FOR EASTERN TRIALS. AGAIN, THE TRAIN PORTER IS UNIDENTIFIED, VANCOUVER, 1934.

SOURCE: CITY OF VANCOUVER ARCHIVES, CVA 99-5032

However, in 1917, four Black porters out of Winnipeg formed the Order of Sleeping Car Porters. They joined the CBRE two years later, causing that union to remove the “Whites only” clause from their constitution.

The Canadian Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters became members of the American union of the same name, and worked with them to fight racism and work injustices. Working in secret so that they didn’t lose their jobs, this body of men eventually succeeded in signing a collective bargaining agreement with CPR in 1945. Their work led the way for future generations fighting for equality and rights.

Some of the names of these train porter activists are Harry Gairey, Stanley Grizzle, and Donald W. Moore, but there were many that lived through this struggle for basic rights.

Upon arrival in Canada, most of these people settled in larger cities, particularly Toronto and Montreal. Though the Black population in British Columbia doubled in size between 1996 and 2016, this province still only holds around 3.6% of Canada’s Black population. Over half of these are first generation Canadians, many of whom came from Africa.

Third Wave: African Immigrants

People of African descent have been arriving in Canada for centuries, beginning with Mathieu da Costa in the 17th century, the first Black person recorded as being in Canada. He traveled to the New World with Samuel de Champlain and Pierre Dugua. Little is known about him, but he was employed by the exploration expedition as a translator, helping to communicate between the French and the First Nations.

For a long time, the majority of Blacks who came to Canada were enslaved, escaped slaves, or freed slaves. Then, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, more Black settlements were established, largely by African Americans looking for opportunity.

Recently, though, Canada has become home to many Blacks who have come here from countries in Africa. Between 1946 and 1950, Africans accounted for only 0.3% of new immigrants to Canada. During the 1970s, this figure was around 5 and 6%. In 2001, 48% of all Black immigrants were from Africa. These people have come as refugees, sponsored families, independents, and entrepreneurs.

AN ARTIST’S CONCEPTION OF WHAT MATHIEU DA COSTA MAY HAVE LOOKED LIKE.

SOURCE: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

A STEADY INCREASE IN IMMIGRANTS FROM AFRICA CAN BE SEEN ON THIS GRAPH. SOURCE: STATISTICS CANADA, CENSUS OF POPULATION, 2016

YASIN KIRAGA MISAGO, EXECUTIVE AND ARTISTIC DIRECTOR OF THE AFRICAN DESCENT SOCIETY BRITISH COLUMBIA.

YASIN STANDS WITH A CANADIAN WOMAN WHO VISITED THE DZALEKA CAMP AND TWO OF HIS STUDENTS, WHO ALSO CAME TO STUDY IN CANADA. ONE WENT TO LAURENTIAN UNIVERSITY, AND THE OTHER TO BROCK UNIVERSITY.

The African Descent Society British Columbia

This exhibit was created in partnership with the African Descent Society British Columbia, founded by Yasin Misago Kiraga, who provided some important starting points for the research done. Yasin was also a speaker at Mackin House Museum in Coquitlam for Black History Month, 2020.

Yasin came to Canada after living many years in a refugee camp in Malawi. The camp was called Dzaleka and it is home to over 46,000 refugees, most of whom came from The Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, and Burundi during the genocidal attacks in these countries in the mid 1990s.

Yasin came to Vancouver and attended the University of British Columbia earning a degree in Political Science and International Relations, and became involved in his new community. In 2014, he started the African Descent Society as a way to connect with the local Black population and to bring attention to BC’s rich Black history.

Here is a link to the website of the ADSBC: https://www.adsbc.org/

This exhibit merely introduces the history of Black pioneers and Black communities in British Columbia. It is the tip of an iceberg. We hope that this overview will spur further interest in the rich history of these people that can be found in images, family stories, and historical documents, as well as in current news and events. Undoubtedly, more information is out there waiting to be found and told.

Interesting Links and Further Reading

When the first settlers came to the Coquitlam area and the lower mainland, their history was not as carefully recorded by the dominant European population. While the Europeans may have been the majority, they worked and lived side by side with thriving black communities whose histories have not always been as carefully preserved. Nevertheless, these people made significant contributions to the BC we know today. They have been here all along. This online exhibit is in recognition of some of the people from our historic and contemporary Black communities, their achievements, and their struggles.

Links

African Descent Society British Columbia

https://www.adsbc.org/

Hogan’s Alley Society

https://www.hogansalleysociety.org

BC Black History Awareness Society

BC Black History Awareness Society – “A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots” – Marcus Mosiah Garvey Jr.

Black Strathcona

Black Strathcona - 10 video stories about Vancouver's black community Black Strathcona

Unity Center Association of Black Culture

https://ucabc.ca/

Salt Spring Island Archives

http://saltspringarchives.com/

Black Baseball history in Western Canada

Negro/Cuban Connection (attheplate.com)

Jim Crow Museum of Racism in Michigan

https://www.ferris.edu/jimcrow/

Black Lives Matter Canada

BLM – Canada – All Black Lives Matter

Black Lives Matter Vancouver

https://blacklivesmattervancouver.com/

Meanwhile, Black in Vancouver…

Meanwhile, Black in Vancouver.... | Facebook

National Film Board film about Train Porters

Playing: Black Communities in Canada: A Rich History (nfb.ca)

Further Reading

Caste, Isabel Wilkerson

They Call Me George: The Untold Story of Black Train Porters and the Birth of Modern Canada, Cecil Foster

Go Do Some Great Things: The Black Pioneers of British Columbia, Crawford Kilian

Blacks in Deep Snow: Black Pioneers in Canada, Colin Thomson North of the Color Line: Migration and Black Resistance in Canada, 1870-1955, Sarah-Jane Mathieu

Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada From Slavery to the Present, Robyn Maynard

Until We Are Free: Reflections on Black Lives Matter in Canada, edited by Rodney Diverlus, Sandy Hudson and Cyrus Markos Ware

The Skin We’re In, Desmond Cole

My Name is Not George: The Story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, Stanley Grizzle (with John Cooper)

![I.L.A. [International Longshoreman's Association] Baseball Team - City League Champions - 1920

City of Vancouver Archives CVA 99-3234](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/64b58897b3cb2437ac2752f6/a1e7c998-80b0-4e6c-894a-1befc041b052/CVA%2B99%2B-%2B3234%2B-%2BI.L.A.%2B%5BInternational%2BLongshoreman%27s%2BAssociation%5D%2BBaseball%2BTeam%2B-%2BCity%2BLeague%2BChampions%2B-%2B1920.png)