Caboose

History of the Caboose

The word caboose comes from the Dutch word “kabuis,” which was a small room on a ship used for preparing food. When trains were first used, military and marine vocabulary was adopted for this new technology. Over the years, cabooses acquired many nicknames. Some of these are crummy, hack, shack, done shaker, cabin or cabin car, van, hearse, buggy, brain box, sun parlour, chariot, throne room, clown wagons, way cars, doghouse, or lookout.

Train rides were often long and required odd working hours. The purpose of the caboose was to provide accommodations for the workers. Generally, two crew members at a time were in the caboose. It was equipped with beds, stove tops, and a washroom. This was also like a home away from home for the crew.

-

The caboose was a mandatory part of trains until the 1980s. When labour agreements no longer required employees to work long hours, there became no need for the caboose. They have been replaced by an electronic End of Train (EOT) device that is mounted on the end of the freight trains.

Not all is lost for the caboose there are still two ways that they are used today. They are used as Maintenance of Way (MOW), which is to ensure that the railway remains clear, safe and navigable, or when trains need to backup, they are used to protect the train.

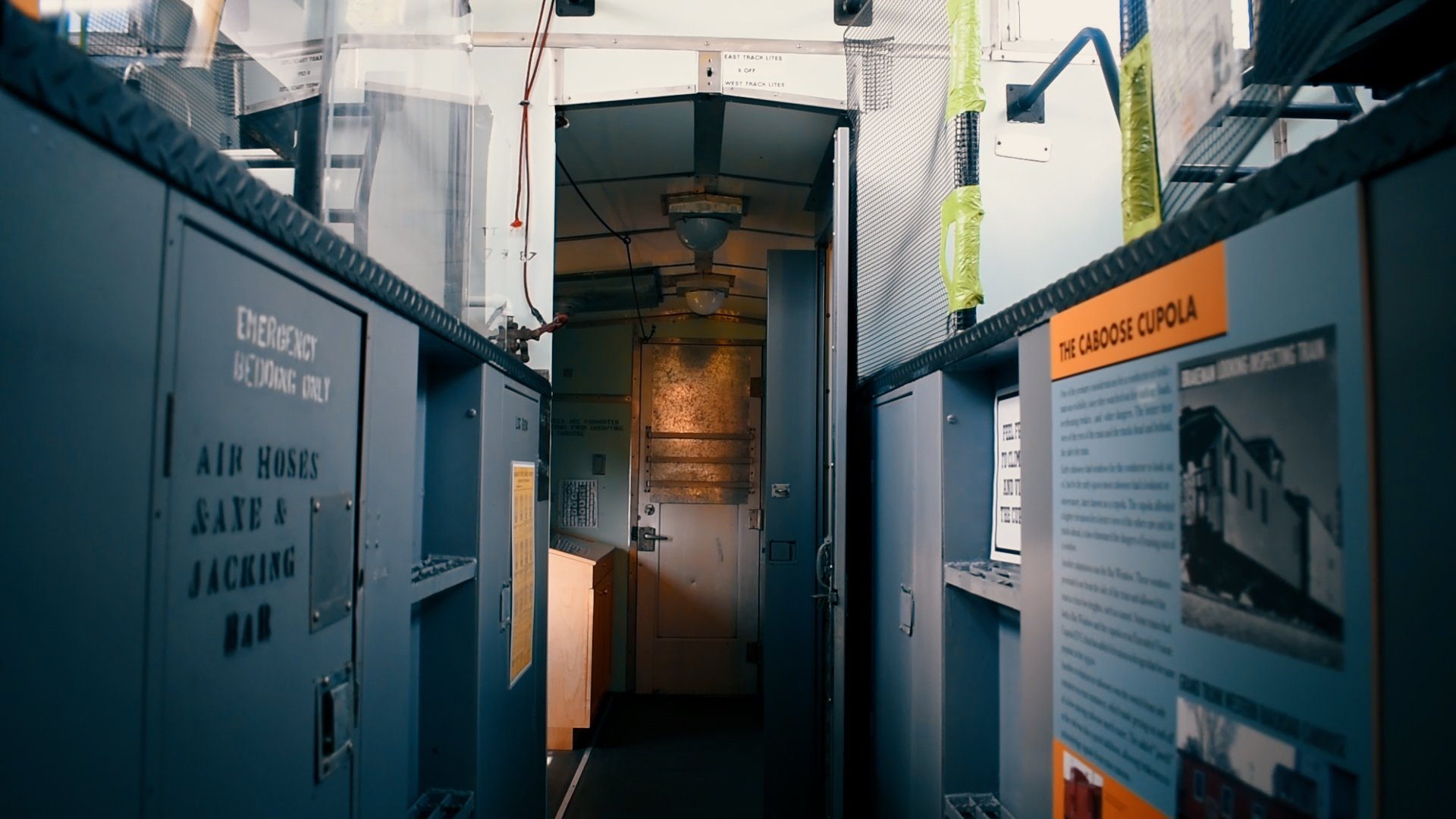

Caboose Sleeping Berth

A typical caboose had three narrow beds for the train crew to sleep in. There were mixed feelings about sleeping in a caboose. Some men slept amazingly, while some disliked sleeping in the caboose. The main complaint was during the wintertime, if the stove fire went out while you slept, it would become too cold in the caboose. Workers would try to avoid entering from the side of the berth to avoid waking up their sleeping co-workers. Later, when the caboose had been taken out of service, workers would take turns sleeping in the front car by the train.

History of Our Caboose

The one that we have in Heritage Square is the Canadian Pacific Railway Caboose #424553 built in the 1970.Our caboose was made by the Angus Shops, a company that was based in Montreal. This caboose was most likely used in Toronto, due to the “T” initial seen in the cupola.

Home Away from Home

The caboose was one the only places on the train that the men could relax and unwind for a brief moment. Despite the caboose’s many degrading names and its uncomfortable nature, it was a home away from home for the crew members.

The men decorated the interiors of the caboose with homey touches, like curtains, family pictures, reading materials and playing cards.

Dangers

-

The caboose was the most dangerous place to work at in the train, as sudden stops caused all the energy to ripple backwards to be absorbed by the caboose. Earlier versions of the caboose were often made of wood, meaning that if the train was rear-ended, it could be fatal to the crew inside. When coal oil lanterns were in use, toppled lanterns could easily start fi res, and crew members had to be ready to hold on to something to avoid too much jostling.

-

Because it was the last car in the train it provided the perfect place to look for signs of danger. Crew members could sit in the cupola and be on the lookout for oncoming trains, dragging equipment, shifting freight loads and anything else that could be a potential danger.

To get the attention of the conductor, in case of danger on the tracks ahead, a fuse or torpedo was used. These were attached to the track and as the train passed over them, they ignited. They were bright and made a loud noise to catch the attention of the conductor and engineer.

-

The brakeman oversaw the brakes of the train. In the early days of rail travel, the train’s brakes were operated by hand. Each train car had its own brake and the brakeman had to jump from train car to train car and put on each brake until the train stopped. It was a dangerous job that resulted in many serious injuries, even death. As train technology improved, automatic air brake systems eliminated this job and brakemen were then employed at coupling and uncoupling train cars, throwing switches on the tracks, and using flares, flags or lanterns to signal other trains. There are still manual brakes on trains, operated by a large brake wheel, but these are only used in emergencies.

-

The chairs in the Cupola are where the crew members would sit on look out for any signs of danger. There was one pointing in each direction. The chairs swivel so that the conductor can look both ways if needed. There is also a red cord that is attached to an emergency braking mechanism (opposite cupola). The cord spans the length of the caboose which allowed a conductor or brakeman to initiate braking from any point within the caboose. As the boss of the train, the conductor was allowed to make sudden decisions regarding slowing down or stopping.

Mud Slides and Forest Fires

One of Canada’s worst ecological disasters was a 1913 rock slide caused by the construction along the Fraser River. This incident severely damaged the coastal salmon fishery, which greatly affected the Carrier First Nation community that lived upstream. Many other rock slides devastated local communities. An estimated 20 percent of the nearby First Nations population would starve or die from malnutrition.

Forest fires were a constant problem. Sparks from passing trains would escape from the locomotive, setting fires that could delay trains or, even worse, destroy the wooden ties and bridges. Fires led to increased floods and destroyed wildlife habitats, resulting in the loss of game for Indigenous people.

Comms

-

Due to the extensive network of the railway, it is not surprising that the railroad industry is a pioneer in improving communication methods.

Experiments with the use of radios in locomotives and cabooses started in the 1930s. It picks up dramatically after World War II, when the compact reliable high frequency two way radio equipment was developed. In 1959, the Pacific Great Eastern Railway in western Canada began the use of microwave radio for all communications. The microwave radio was adopted by the rest of the world in 1970, since it was one of the first reliable radios that was able to check all the boxes of communication needed for the crew and ground traffic control. Today, the railroads are the largest operators of electronic communication

methods. In many trains, we can now find high-capacity optical-fiber cables, which are lightweight and much more immune to electromagnetic interference. They can also integrate voice, data, and video channels in one system.

An End of Train Device (ETD)can be as simple as a red flag attached to the last car of the train, or modern smart devices that monitor things like brake line pressure and accidental separations (motion sensors). All this was previously performed by the crew in the caboose. The ETD, in Canada also known as SBU (Sense and Brake Unit), transmits its information to the locomotive.

-

Before radio communication became more effective in the 1940s, and even sometimes afterwards, railway workers communicated with each other along the tracks by using train whistles, flares and lanterns, flags, and various hand signals. Communication along the tracks included communication between the caboose and other parts of the train, between different trains, and between the train and the station, with their own variety of different signal methods.

All the methods of signalling had to be preformed correctly to ensure the safety of the workers, passengers, and the people living around the train tracks. The employees involved in signalling had to prepare themselves with the proper tools and appliances to always be ready for immediate use. Carelessness could result in loss of life and or destruction of property.

-

All hand signalling must be given from the track in a way that could not be misunderstood on the part of any of the workers.

Any object waved violently by anyone on or near the track is a signal to stop. The absence of a signal where one is usually shown must also be regarded as a signal to stop.

-

Lanterns and Flags were used to communicate information between all levels of workers aboard the train. The flags were used during the day, while the lanterns were used during the night. Night signals had to be displayed from sunset to sunrise or when the weather or other condition obscure the day signals. Flags and lanterns were not only used at the front of the train but on the back, also known as the Leading light.

Examples of different combination of flags and lamps are two white flags or white lanterns on the front of the train which indicated that it was a “special” or “extra train,” not a regular scheduled train. Two red flags or red lanterns lights were used to flag and stop trains between stations to prevent collision or warn of an obstruction on track.

-

Engine Whistle Signals, which may also be referred to as the engine horn, is used to communicate messages. Similar to Morse code there were short blasts and long blasts to produce a variety of responses to a various signals.

-

Fuses operated similarly to flares, they are used in extreme circumstances. They are normally thrown or placed on or near the tracks by the flag man to indicate danger to approaching trains, that they must reduce speed. Fuses will burn for about 10-20 seconds.

Cupola

One of the primary considerations for a conductor or brakeman was visibility, since they watched out for shifiting loads, overheating brakes, and other dangers. The better their view of the rest of the train and the tracks head and behind, the safer the train.

-

Early cabooses had windows for the conductor to look out of, but by the early 1900s most cabooses had a lookout or observatory, later known as a cupola. The cupola afforded a higher elevation for a better view of the other cars and the tracks ahead, it also eliminated the dangers of leaning out of a window.

Another adaptation was the Bay Window. These windows protruded out from the side of the train and allowed the train to clear low heights, such as tunnel. Some trains had both a Bay Window and the cupola or an Extended Vision Cupola (EVC) that has added elevation a design that became popular in the 1950s.

Another evolution in cabooses was the switch from side entrances to rear entrances, which made getting on and off of a slow moving caboose much easier. The added “porch” at the end was also a good addition, allowing brakemen to acknowledge signals from train stations.

Stowaway Species - Railroad Ecology

Stowaway species are non-native organisms displaced from their original location and dispersed through new ones by transportation, often via railway lines.

-

You will often find non-native plant species originating from railway tracks as seeds and grains fall from shipping crates or are unintentionally transported by passengers through clothing. The tracks also provide “corridors” which cuts through various environmental barriers (like mountain ranges), creating a passageway for new plant species to spread. In North America, this has led to the spread of trees like the Varnish tree and the Foxglove tree, which are native to China, the Siberian Elm, which is native to Central Asia and Russia, and the Norway Maple, which is from Central Europe.

Studies found that berry productivity along railway edges tended to increase with elevation due to it being a more suitable temperature while also being far away from human interference. Buffaloberry, a main resource for bears going into hibernation, produced more fruit, ripened faster, and had a higher sugar content in the shrubs located within 15 m of railways. Railways were found to increase both the quantity and quality of native and non-native vegetation, which creates a risk as this vegetation then attracts more bears into the area. In the mountain parks of Canada, train strikes have become one of the leading causes of bear mortality.

In addition to increased vegetation along railways, wildlife are also often attracted to the area due to spilled agricultural products.

Graffiti

-

From Italian, plural of Graffito “a scribbling.”

A diminutive formation from Graffio “a scratch or scribble,” from Graffiare “to scribble.”

Ultimately from Greek Graphein “to scratch, draw, write.”

-

If you Google “graffiti” you will see a series of photos of graffiti, followed by the term “visual art genre.” Since the 1970s, many people have considered graffiti to be a legitimate art form, evolving into a unique style that can be seen in galleries, murals, and even in competition; Street Art of the Year is a global competition that celebrates street art in all forms.

However, graffiti is still controversial, with much of the debate coming down to permission. If an artist has permission to create in a public space, then it is art; if they do not have permission, it is vandalism. As David Maddox says, “Graffiti and street art can be controversial, but can also be a medium for voices of social change, protest, or expressions of community desire.” Just ask permission first.

-

Graffiti in a basic form was present on railroads as early as the 1900s, with its presence growing during the Great Depression. During these times, hobos – those traveling the country looking for work and hitching a ride on freight trains – and even some railroad workers became known for creating chalk drawings and murals on the inside and outside of cars.

-

Contemporary graffiti dates to the late 1960s and was catalyzed by the invention of the aerosol spray can. Early graffiti artists were commonly called “writers” or “taggers.” To tag is to write a stylized signature; the goal is to tag as many locations as possible. An important principle of graffiti practice was the intention to “get up,” or to have one’s work seen by as many people as possible, in as many places as possible. The exact geographical location of the first “tagger” is difficult to pinpoint. Some sources identify New York (specifically taggers Julio 204 and Taki 183 of the Washington Heights area), and others identify Philadelphia (with tagger Corn Bread) as the point of origin. New York heralded as a place “where graffiti culture blossomed, matured, and most clearly distinguished itself from all prior forms of graffiti,” explains Eric Felisbret, former graffiti artist and lecturer.

After graffiti began appearing on city surfaces and subway cars, trains became major targets for New York City’s early graffiti writers and taggers. Trains traveled great distances, allowing the writer’s name to be seen by a wide audience. The subway rapidly became the most popular place to write, with many graffiti artists looking down upon those who wrote on walls. Graffiti on subway cars began as crude, simple tags, but as tagging became increasingly popular, writers had to find new ways to make their names stand out. Over the next few years, new calligraphic styles were developed and tags turned into large, colourful, elaborate pieces, aided by the realization that different spray can nozzles (also referred to as “caps”) from other household aerosol products (like oven cleaners) could be used on spray paint cans to create varying effects and line widths. It did not take long for the crude tags to grow in size, and to develop into artistic, colourful pieces that took up the length of entire subway cars.