Working the Railway

Sleeping Car Porters

American entrepreneur George Pullman invented the “Pullman Sleeper Car”in the mid-1800, and in the 1870s’ the sleeper car was introduced in Canada. The idea of the sleeper cars was to intertwine comfort, luxury and overnight train travel. The seats were converted into beds, and bunks could be pulled down from the wall. Privacy curtains, chandeliers, walnut panelling, and upholstered seating provided luxury and comfort while travelling by train. The overnight travelling experience was not complete without the high level of service done by the sleeper car Pullman Porters, also known as “George’s Boys.”

-

In both the United States and Canada, the majority of the sleeping car porters were Black men. They were the preferred hire because of racial attitudes which perceived Black people as good domestic workers.

Canadian Porters were hired from cities that had well – established Black communities, such as Hogan’s Alley in Vancouver, Africville in Halifax, Little Burgundy in Montreal, and Bathurst and Bloor in Toronto.

The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) was one of the few opportunities for employment for Black men at the time. Many Black workers were highly educated and overqualified for their service work.

Porters would attend to every passenger’s needs and wants. They provided various services such as carrying luggage, pressing clothes, setting up beds, shining shoes, and serving food and beverages. At times they were also babysitter for children, the elderly and drunk passengers.

Discrimination and Poor Working Conditions

Canadian railway companies ensured Black Porters had little power and autonomy. They were exploited and worked in poor conditions, since they were seen as easily replaceable by their employers.

-

The Porters were expected to work 24 hour shifts throughout the duration of the trip. In many cases the passengers’ requests would interrupt their sleep or the little downtime they could muster. They were lucky to get three to four hours of sleep a night. Despite working consecutive day trips, porters were not provided berths to sleep. They were only allowed to sleep on the men’s smoking-room floor with poor air quality.

Like many other labour intensive jobs in Canada, Black Porters were paid less than their white colleagues. They were also not eligible for promotions or to apply for higher positions. They would enter as Porter and would leave 10-20 years later as Porters. In many cases they had to pay for their meals and uniforms out of pocket.

Black Porters could be fired at any moment. If a customer complained or accused, a Porter of stealing, they would be dismissed; in this line of work the customer was always right, even if their accusations were false.

Even with all the discrimination, racism, and poor working conditions, being a Porters was a desired position due to the few employment opportunities for Black men at the time.

Unionization

The most powerful railway union was the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees (CBRE). The constitution ruled that only white people could be members, barring Black railway employees from joining. The Order of Sleeping Car Porters (OSCP) was formed in 1917 in Winnipeg by John A. Robinson, J.W. Barber, B.F Jones, and P. White. OSCP was the first Black railway workers union in North America.

Despite operating without the support of the CBRE and facing institutional racism from the Canadian National Railway (CN), they secured two contracts with the CN. The contracts improved wages and job security for all porters. In 1925, Black railway workers started the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) in the United States and opened memberships to Black Canadian porters in 1939. Divisions were established in Toronto, Winnipeg, Montreal, Edmonton, Calgary, and Vancouver in 1942.

-

The Canadian Pacific Railway had strict anti-union rules and forced employees to sign clauses prohibiting union participation. The BSCP worked discretely on unionizing CPR porters. Finally, in May 1945, a collective bargaining agreement was reached with the CPR. Monthly salary increases, one week of paid vacation, reasonable hours, and more transparent disciplinary measures were established. The union negotiated a better working schedule and a reserved berth for each porter so they could sleep more comfortably.

The fight for equality and fair treatment was far from over, as racist attitudes were rampant in the workplace. Black porters continued to fight for higher positions in the company. The BSCP filed an official complaint with the Federal department of Labour. One of the complainants, George V. Garraway, was the first Black Canadian hired as a conductor in Canada.

Unions have long been a part of Canadian rail history, first established to guarantee fair wages and hours for rail workers as railways were built across Canada. Although originally established as small, local organizations, unions rapidly developed during the early 20th century, forging ties and often merging with British and American unions. As the unions grew during the Great Depression and WWII, they organized large strikes and became professionalized. They established nationwide labour congresses and advocated for labour rights to be enshrined by the emerging postwar welfare state, giving workers bargaining power against the state-owned railway companies. This was particularly seen during WWII, when unions pushed for the right to strike and used the challenging circumstances to improve industrial relations; combined with strikes that swept across Canada in the postwar years, this resulted in major improvements in wages and hours, as well as other benefits such as vacation pay.

One of the first Canadian rail workers’ unions, the United Brotherhood of Railway Employees (UBRE), was established in Winnipeg in 1898 after an offshoot of an American union closed its office. UBRE was at the forefront of several significant strikes, one in Winnipeg in 1902 and another in Vancouver in 1903, and caught the attention of both the CPR and provincial government; the CPR was determined to crush the UBRE and a royal inquiry was launched into the union due to its socialist ties. Although it merged into the International Workers of the World in 1905, it set the stage for railway labour unions across Canada. The most well-known union was the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees (CBRE), established in Moncton in 1908.

However, rail workers’ unions in Canada have a dark history of exclusionary policies – many did not allow Black or Asian members, with the CBRE explicitly banning black membership until 1919. This led to the establishment of perhaps the most famous Canadian rail workers’ union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), in 1917. The Brotherhood merged with its American counterpart soon after forming, thus creating the first and largest Black union – at its peak, the BSCP had 18,000 members across North America.

Today, rail workers’ unions are still very active. Many unions forged alliances, and eventually merged with larger international unions, with the Canadian rail workers’ union being part of the IWW.

Working on the Train

For most of the 20th century, workers on the railroad were a conductor, a brakeman, an engineer, a flagman, and a fireman.

The conductor was responsible for the whole train. They would check for car waybills, wheel reports, and switch lists, among other things, while managing the train’s operation. They needed to know what they are carrying and take the proper precautions to keep their co-workers and cargo safe while travelling:

Waybills are forms used on railroads to help route each car from its origin to its destination.

Wheel Reports gave information on the state of the train’s wheels on every car.

Switchlists gave all the information on the work needed for each car at each location.

-

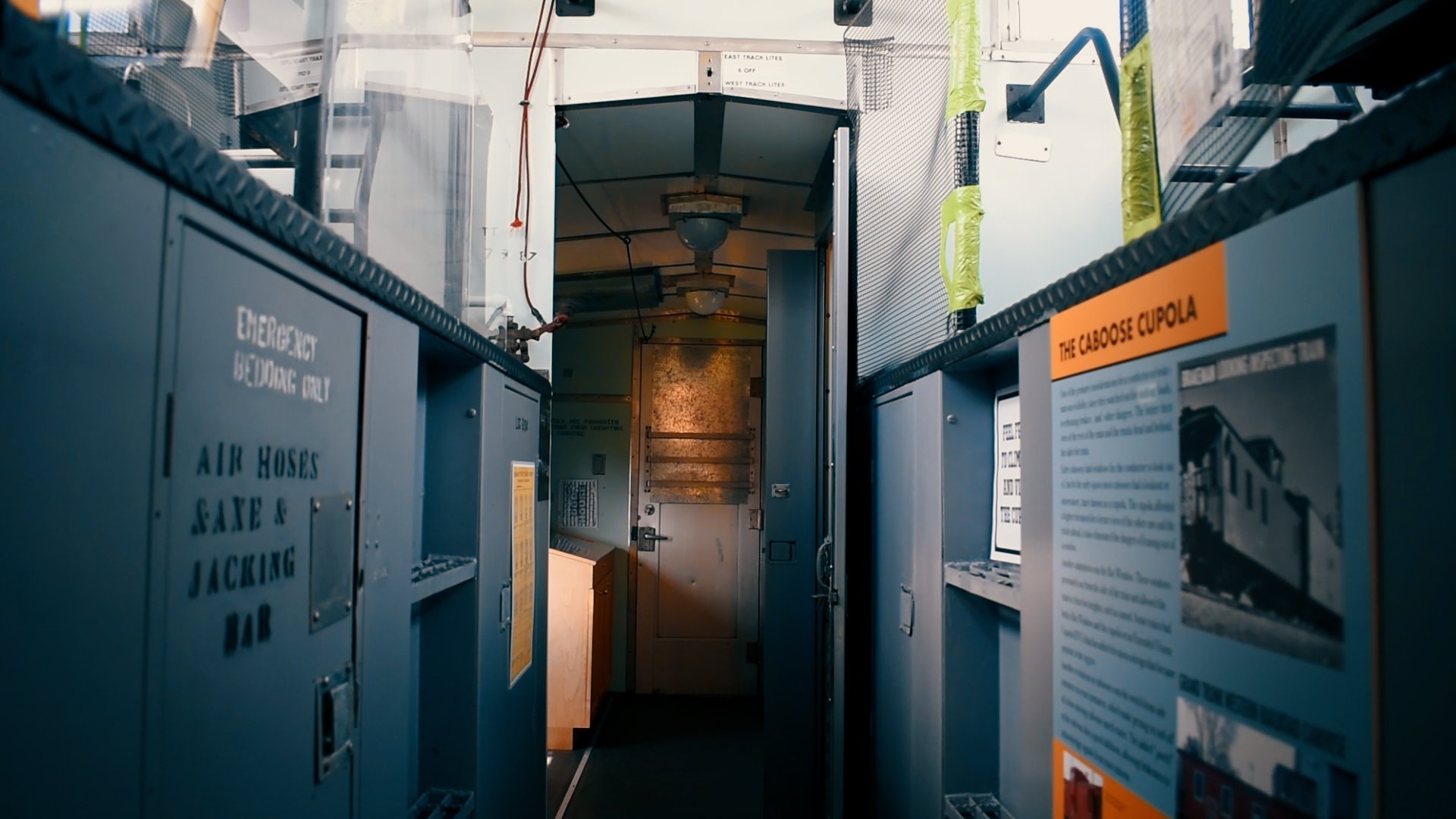

The brakeman oversaw the caboose identification markers, the throw switches and the coupling and uncoupling cars. When the train was moving, they kept an eye on its cars and potential hazards. The senior rear brakeman rode in the caboose while the head brakeman rode in the engine room. They are also known as a Trainmaster.

The flagman would walk a safe distance behind the stopped caboose carrying a lantern, flags and fuses to signal approaching trains of track issues along the way.

The engineer oversaw safety and efficiency of the locomotives. The engineer had to know the function of the train like it was second nature. The engineer must respond to the breakman and the conductor.

The fireman stoked the fire and maintained the steam pressure in the boiler. Once diesel became the primary energy source, this part of the work disappeared. Nowadays, they assist the engineer with watching the tracks and signals. Sadly the need for a fireman is becoming less and less.

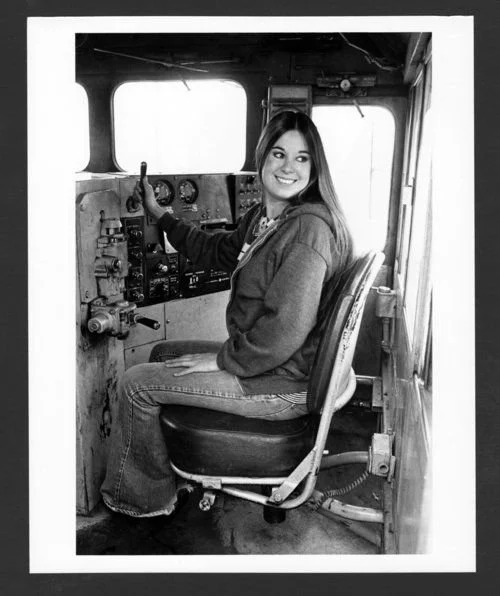

Women on the Railway

During World War I, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) lost men of military age as employees. This was especially evident in 1917 and 1918. As a result, the CPR hired more boys, older men, and to a very limited extent, women. About 1% of the workers in the Mechanical department were women. Most of these women worked as car cleaners.

-

Cheryl Chamberlain grew up in a railroading family. Her father and grandfather were conductors. In 1979 Cheryl Chamberlain began working for the CPR at the switchboard. Eventually, she moved up to a crew caller, a senior clerk, and a machine clerk. During this time, only specific jobs were available for women. Women in the workplace were rare and Cheryl learned to grow tough skin to survive the environment. Although there has been an increase in women railroaders since 1979, the railway, even today, is a male-dominated industry. In January of 2022, Canadian National Railway (CN) named Tracey Robinson as CEO. This is the CN’s first female leader in its 103-year legacy and the second female railroad leader in the entire history of North American railroads.