Intersectionality and Urban Spaces

Frequently an abundance of signage is used. Speed limits are posted along with warning signs, and police are placed to enforce these rules. This fails to remedy the issue as signs can be, and often are, ignored by drivers. They can be confusing, and not obvious to a wide range of people from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds.

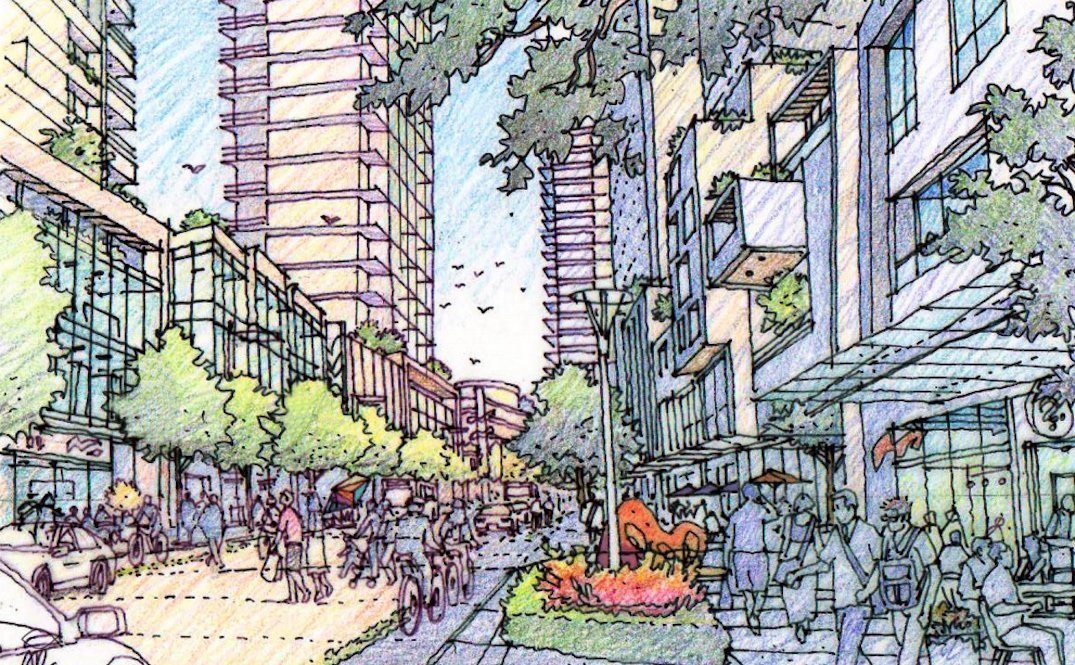

Streets and sidewalks are an essential part of urban life. Such places can be dangerous and difficult to navigate as cars, pedestrians, cyclists, and others contend with one another.

Better design can remedy these issues. Twisting roads or other features can force cars to slow down without using signage. Some European cities have removed sidewalks, making the road an equal space for vehicles and pedestrians. Cars are forced to slow down, and drivers and pedestrians need to cooperate in order to effectively negotiate the space.

The sidewalk is one of the most neglected places in North American cities, often viewed as a secondary to the car. Jane Jacobs argued that the sidewalk is one of the most important aspects of the city. She claims that it should be treated as a place itself, where people can interact and be a home for shops and services.

Many places in North America lack memorability, or the ability for people to form a connection. When people care about a place, they are more likely to act carefully and share the area with others. This also aids in navigation, as people can move between memorable nodes, as opposed to abstract directions through identical-looking streets.

The number of people and connections to the place helps it to stay safe and clean. Through better design, the sidewalk and the street can work together to act as one shared space for both pedestrians and vehicles

Image Credit

Ryota Iwata on Unsplash

Jason Dent on Unsplash

Over the past century, there have been a wide range of different public transport options in Vancouver and its surroundings. One of the city’s earliest public transport systems was the Interurban railway. It was created on a small scale in 1891, and soon expanded to cross from North Vancouver to Coquitlam. In some areas this early system remained until 1979, however, by the 1950s, most services had ended as buses were becoming more common. Coquitlam and other connected municipalities saw their railway connection end around this time.

Photograph of the Burnaby Lake Interurban in the snow.

City of Burnaby Archives, BHS1996-14

Photograph of the interior of a Central Park Interurban while it is in service in Vancouver.

City of Burnaby Archives, BHS2007-04

Public transport systems are a vital part of a city’s infrastructure as they allow people without a car a wider area of access to the city. A key feature of public transport networks is accessibility. People without the means to own a car, or who can not operate a car, rely on public transport. Even the simple fact that dogs are prohibited from public transport severely limits people without a car to partake in leisure activities like shopping or sight-seeing.

All facets of the network must be made accessible, a train station with braille is no use if the bus that takes a person to it lacks the same feature.

The increased focus on automobiles and buses worsened traffic issues. A solution was needed to allow people to take long-distance public transport without having to suffer through traffic or multiple bus connections. By 1975, the first plans for what would become the SkyTrain began to develop. It took nearly a decade to come to fruition, the first SkyTrain line, named the Expo Line, opened in 1986 for Vancouver’s World Fair. The system would soon expand to encompass large areas of Metro Vancouver, including Coquitlam.

Play spaces for children are often designed to be as safe as possible, sometimes even described as “lawsuit proof.” These spaces are not the best for children as its lack of risk can cause children to seek out more dangerous action than modern playgrounds were designed for.

London Adventure playground, 1960. Warning: Mild violence and toy weapons

In Europe, and some parts of the United States, so-called Adventure Playgrounds or Junk Playgrounds have appeared. These play areas developed during the Second World War in Copenhagen, where Architect, Carl Theodor Sorensen, first noticed children making use of scrap materials and abandoned areas for playing. Comparing riskier playgrounds in London, England to safer playgrounds in San Francisco found that kids are 18% more physically active in London.

The idea behind adventure playgrounds is that risk management is a crucial skill for children. Adventure playgrounds feature tools like hammers, nails, and saws for children to use and build their own play structures. Allowing children to create structures puts them in control of their own risk, they are given the ability to create a play environment that has a risk level comfortable to them.

The playground at Van Saun Park in Paramus, New Jersey, Wiki Commons

Many of these playgrounds have paid staff to ensure that nothing gets too far out of hand, but, for the most part, they won’t intervene. Signs instruct parents to not offer advice. Rebecca Faulkner, Executive Director of the nonprofit that runs The Yard, an adventure playground in NYC, puts it best in saying that “children are better at figuring out how to have fun than many adults who build playgrounds for them.”

These spaces give children a place to call their own, something that they often attempt to carve out in the urban landscape. Many older people have fond childhood memories of unsupervised and less organized play areas.

Hostile architecture is any form of infrastructure that is designed to restrict the usage of the space. The term is most often used to refer to built environments that prevent unhoused individuals from using the space. In their simplest form, they may be spikes or fences blocking access to sheltered areas used for sleeping. These forms often draw negative attention from the public because rather than hiding the issue of homelessness, they act as a reminder.

Rather than addressing social issues, these alternative methods are employed with the intention that they go unnoticed by those they do not affect. The most common of these methods are benches with dividers or rails that prevent a person from sleeping on them. This deterrent works to simply push people away, rather than create a sustainable solution to the issue. Other examples include fi lling alcoves with large and heavy potted plants or art pieces, playing music or keeping bright lights on all night to discourage people from sleeping in the area. Garden sprinklers in fields or planters may also be designed to spread onto walkways at night to stop people from staying there.

So-called Mosquitoes emit high-pitched noises that cannot be heard by people over the age of about 20. These deter young people from loitering in front of stores.

Purple or blue streetlamps or bathroom lights are intended to deter IV drug users, as they make it difficult to see veins under the light.

Image Credit: Filip Mroz on Unsplash

Neighbourhoods mostly made up of a single ethnic or racial group are considered segregated. This is predominantly the case for Black or Asian communities. Vancouver has a prominent Chinatown, which has existed in some form since the mid to late 1800s and Steveston in Richmond which was a historically Japanese neighbourhood.

Image Credit: Patrick Tomasso on Unsplash

There are many reasons why different groups end up living separately from one another. Often multiple factors are working together to drive the divide. Following the Civil Rights Act in the 1960s, American cities could no longer discriminate based on race directly. However, developers and planners found new ways to economically force Black Americans out of White neighbourhoods. Pricing schemes and the prevention of African Americans from achieving a higher socio-economic status through factors such as job discrimination forced many to remain in low-income urban centers. With time, these communities continued to cement themselves, making neighbourhoods more and more racialized.

Gentrification is another common practice in North American cities. This involves developers buying up large amounts of cheap land, often inhabited by marginalized groups, and forcing them out through increases in pricing and rent to redevelop the land and sell it to wealthier White families. Gentrification also affects jobs, for example, industrial districts are gentrified, causing many jobs that low-income groups rely on to disappear.

The Sociologist, Ray Oldenburg, created the concept of “third places.” The idea was that this third place - the other two being home and work/school - increases social cohesion. They are the glue which holds a community together. It is a home away from home, a place to relax.

To function comfortably, this third place needs to be a space where people just pop in and out, and it is free or cheap.

The idea of gathering spaces has been around for a long time in the form of cafes, clubs, bars, libraries, churches, parks, plazas, barber shops, marketplaces and communal areas. It was a place to exchange ideas and discuss public matters. Oldenburg writes that such places create social connectedness.

Loneliness has become a big concern for modern societies which was also amplified by the Covid-19 pandemic. Surveys from the US find that half of all Americans are lonely, and 40% of people in the UK report that their major source of companionship is either a pet or television.

Loneliness can have a drastic impact on a person’s life, cutting life short by up to 15 years, and increasing the risk of stroke and cancer.

Increased levels of online activities, a generally declining social participation as well as dependency on cars, necessitated by urban sprawl and a host of other factors contribute to this decline.

During the pandemic, video conferencing and e-gaming firmly established themselves, and the home functioned both as a home and workplace.

Society still needs physical third places for random conversations and to discover commonalities. This needs to be considered and to be revived by urban planning.

Walkable and mixed-use main streets and town centres, as well as meeting zones like gardens and parks in residential zones, can create this valuable third place.

Image Credit

Chuttersnap on Unsplash

City of Coquitlam

Austrian-American Architect, Victor Gruen (1903 to 1980), noticed how much time Americans spend in cars, often with little interaction. People’s primary place was home, the second place was work, Gruen’s hoped to create a third place (based on sociologist Ray Oldenburg and Gruen’s ideas), particularly in suburban places. To give people a third place, Gruen came up with the concept of the mall. A centralized space - much like a European city centre.

In the lean 1930s when Gruen started thinking about a centralised space, he was also worried by how little money people spend. His solution to increase commerce were beautifully designed storefronts to entice people to spent more money and time. His plan was a mall that offered shops and other amenities surrounded by greenery with cars parked all around.

Pillars with a View (Craig Hodge, Columbian Company fonds, F8-S1-F16.2, City of Coquitlam Archives)

Gruen’s full vision for the mall was more than just shops. He imagined them as mixed-use facilities, with apartments, offices, medical centers, child-care facilities, libraries, and (since it was the 1950s) bomb shelters.

Gruen theorized about shopping malls long before he ever built one. Eventually in 1952, the owner of Dayton Company commissioned him to build the very first indoor, climate-controlled shopping center in Edina, Minnesota.

Aerial of Coquitlam Centre and Surrounding Area (Bob Dibble, Croton Studios Ltd., Enterprise Newspaper fonds, F6.761, City of Coquitlam Archives

Spaces must be designed to accommodate people with differing abilities. Neurodivergent people experience the world differently. The sensory environment is important to neurodivergent people as they may find things like the noise of an electric fan deafening, preventing them from concentrating on other tasks.

Large open spaces may evoke feelings of distress. Public space could be designed with zones that offer smaller spaces for distinct purposes to be assigned, for example, distinct a reading area, and a bookshelf area, separated from the larger library space. Areas may be separated physically, or with colours, different carpets, designs on the wall, or many other things. Even pedestrian zones can offer smaller compartmentalized zones. For example creating slower, quiet zones on the busy streets using trees and green features.

The idea of a Sensory Recalibration zone is to create transition zone between fast (cars) and slow (pedestrians) moving traffic. This idea seeks to build a calm zone with trees or green, a accessibility assisted zone, a pedestrian zone followed by a bike line and eventually the road. This provides calm places and allows to slowly getting used to the road with its barrage of sounds, movement, smells, lights and signage.

Such spaces can be planned for public transport locations, schools and universities, malls and other locations.

Having spaces that lack high sensory experiences can be essential to anyone feeling overwhelmed by stimuli. These escape spaces allow for people to remove themselves from overwhelming experiences like large crowds.

Many things that may seem mundane to neurotypical people can be extremely overstimulating to neurodivergent people. Other examples are fluorescent lights and the low hum they emit or concrete buildings which tend to echo and reverberate sound.

Many urban centers have begun to rethink how they operate and zone themselves to improve the experience of residents and their carbon footprints. For many decades, cities have been dominated by the automobile. People lived in the suburbs and commuted on highway networks to their job, separating them from one another, as well as creating massive amounts of greenhouse gas emissions.

From Centers for the Urban Environment: Survival of the Cities by Victor Gruen

Following the rise of the automobile and an increasing proliferation of suburbs in the USA and Canada, many cities began to separate residential and commercial buildings. This went against the design of many cities which had mixed-use commercial and residential buildings, with shops or services on the ground floors, and residents above. Since the 1990s, these zones have begun to return. They offer many advantages, letting people live closer to where they work. Jane Jacobs was a strong supporter of these types of buildings as she felt they created a stronger and safer community, as storefronts were able to keep an eye on the street. The increased foot traffic helped to build relationships and a sense of community as people saw one another more often.

Some designers have thought of new ways to create better spaces for people to interact with one another in their neighbourhoods. Buildings can be grouped with parks and walkways between them allowing for shared space. Designers have noted that people are more likely to use and maintain the space if they feel a connection to it, this may come in the form of community gardens. The hope behind many of these developments is to foster a stronger sense of community as people are more likely to interact with and build relationships with one another if they cross paths more often. Some other important principles are that of enclosure, proximity, and scale. These design principles ensure that spaces are built to a human scale, to avoid them feeling like chasms between two huge skyscrapers, or empty and wide open fields.

Horse-drawn garbage wagon, in the french town of Hennebont.

Horse-drawn garbage wagon, near Belmont and Pike, Seattle, Washington, 1915. Wiki Commons.

In some parts of France, and one small town in Vermont, horses are used for garbage collection. The horses are quieter than their gas-driven counterparts. Also, they do not emit the same amount of greenhouse gas. Horse-drawn vehicles and machines were once the backbone of cities and farms before the advent of cars and other machinery around the turn of the 19th century. In some sense then, the use of horses represents a return to form. Some municipalities in France even use the animals to pull carts that take children to school.

Cities are a collection of stories stacked up on each other over time and space.

Remnants of the past linger, whether through a street name, a plaque, or the lasting impact on community members who remain.

Imagine them as repositories of cherished memories and traditions, where beloved buildings are sometimes torn down to make way for new ones.

But what’s even more important than the tales of the past, are the stories that remain untold and the experiences concealed beneath the surface, waiting to be discovered and shared.

Regrettably, cities are often designed without consideration for those stories and groups on the periphery, leading to the omission of certain communities (typically marginalized individuals) from shaping our built environments and municipal policies. This omission has far-reaching consequences, that impact the well-being of all of our communities.

But what would our cities look like if they were planned at the intersections? A holistic approach to city-building and taking stock of the voices that are so often ignored in our city processes is what is needed. By acknowledging, working with, and integrating the ideas of diverse groups, we can unlock innovative solutions that address multifaceted challenges and improve our cities for all.

A predominance of generic chain stores does not necessarily mean that particular immigrant communities are not catered for by them. However, many commentators have been critical of the impacts of corporate mall dominance on the diversity of small business opportunities.

Newcomers in Canada on top of facing a new climate, new language, and new everything, also have to deal with new diets and ingredients. This can create challenges as they try to find and cook foods that connect them back to their roots. This can contribute to declining mental and physical health and increasing food insecurity rates among newcomers.

New immigrant communities become visible through the opening of restaurants, or other small businesses focused on the needs and interests of their community. These businesses provided important economic opportunities for new arrivals, as well as establishing their place in the community.

High street-based shopping environments offer local communities relatively greater opportunities in opening a business as generally there are lower rents. In contrast, corporate shopping malls are more tightly controlled, with a strong preference for a specific mix of retail functions and familiar branded retailers to minimize risk as perceived by investors.

This is where an initiative out of Toronto called The Abibiman Project, founded by Chef Rachel Adjei steps in. By harnessing the potential of food to create intercultural ties, The Abibiman Project celebrates African cuisine, cultures, and people, all while supporting broader food security efforts in the city.

The Afri-Can Food Basket works towards establishing food sovereignty for Toronto’s Black community, which is particularly affected by the issue of food insecurity. In Canada, Black households are 3.56 times more likely to be food insecure than white households.

Afric-Can has created programs for marginalized communities to exercise self-empowerment and gain access to healthy organic foods while a the same time using food to develop youths’ life skills. Since 1997, AFB has worked on over 100 Community and Back-Yard Gardens

When it comes to cities, unfortunately, children and youth are sometimes an afterthought in urban processes and design. This is revealed through the design of the built environment, for example through the lack of playgrounds and public spaces, but also vehicle-oriented speed limits and street layouts that lack pedestrian crossings and make travelling to and through these spaces unsafe and ultimately inaccessible. High hedges (decreased line of sight), or signage that is too high can also affect how safely children can navigate the street.

However, designing cities with children and youth in mind is so important that in 2018, UNICEF released a handbook on child-responsive urban planning that provides guidelines and the benefits of making the urban landscape more child-friendly that a) outline how essential play spaces are to vibrant communities, and b) further emphasize that when you design for the health and safety of children and youth in mind, you design for the health and safety of the broader community as well!

One organization that’s working to ensure that cities are more child-friendly through its various initiatives is based out of Accra, Ghana and is called the Mmofra Foundation.

What makes the Mmofra Foundation so interesting is its long history of children’s advocacy sparked by Efua T. Sutherland, the founder of the organization and famous cultural advocate, playwright, and author. According to the Mmofra Foundation’s website, Efua “presided over Ghana’s ratification of the United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of the Child (making it the first country in the world to do so)” and who from 1981 to 1991 was the chairperson of the UN’s National Commission on Children.

Mmofra Foundation incorporated play in unconventional spaces of the city such as the bustling marketplace through their Playable Markets initiative. To beautify a city and make it smart, urban developers often give less attention to human needs, prioritizing roads and buildings. Many cities are technologically smart but not human smart, especially for a large proportion of the population who is under 18.

According to urban planner, Timothy Duin, “By 2030, the majority of the worldʼs urban population will be children. By considering childrenʼs perspectives when planning urban areas, we can design cities that meet our needs now and into the future. We need to design spaces for all ages, abilities and backgrounds to enjoy together.”

Children represent our future. As the urban populations are growing there is an increase in the number of children growing up in an urban setting; it is time to center them when planning.

Most of the public spaces are designed by adults excluding children. Limiting them to only the playground will restrict their creativity and curiosity.

The podcast, Urban Limitrope, and talks with Alexandra Lambropoulosis were the inspiration and basis for this exhibition.

Urban Limitrophe, founded in 2020, by Alexandra Lambropoulosis, is a Toronto-based, bilingual, podcast exploring the various initiatives happening in cities across Africa and Canada to creatively solve problems, support communities, create vibrant urban spaces, and build better cities overall.

Play is fundamental to children’s development and shapes their capacity for learning and social growth, particularly in the early years. Free and unstructured play in the outdoors boosts problem-solving skills, focus and self-discipline. Socially, it improves cooperation, flexibility, and self-awareness. Emotional benefits include reduced aggression and increased happiness. A study published by the American Medical Association in 2005 concluded, “Children will be smarter, better able to get along with others, healthier and happier when they have regular opportunities for free and unstructured play in the out-of-doors.”

UNICEF Shaping urbanization for children handbook 2018