Chinese Immigration Act, 1923

Coquitlam Heritage Society would like to thank the following:

Albert for sharing his family history

Rosalie Gunawan Education & Public Programs Coordinator | Chinese Canadian Museum

Catherine Clement Curator “The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act” A National Commemorative Exhibition & Archive

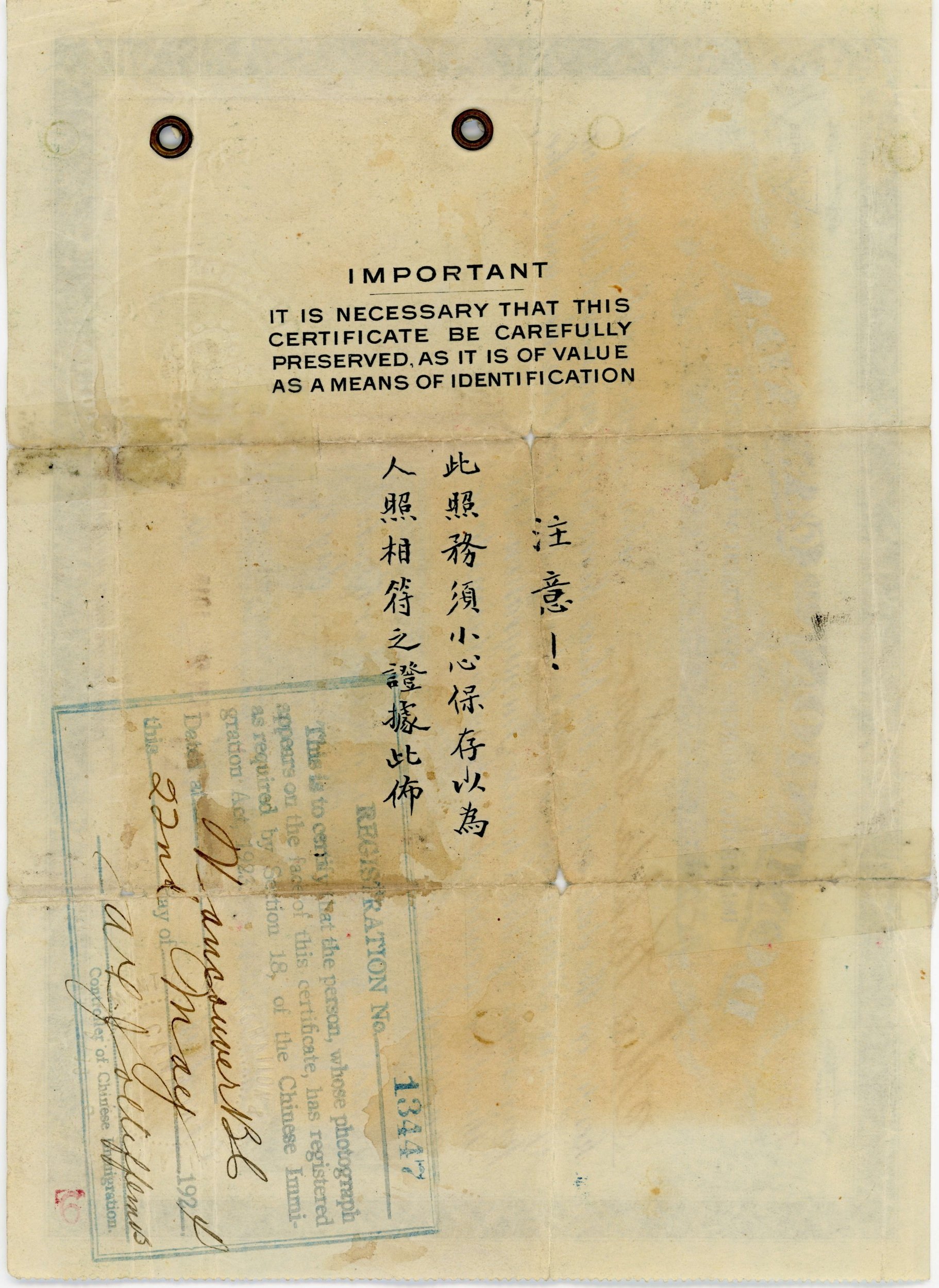

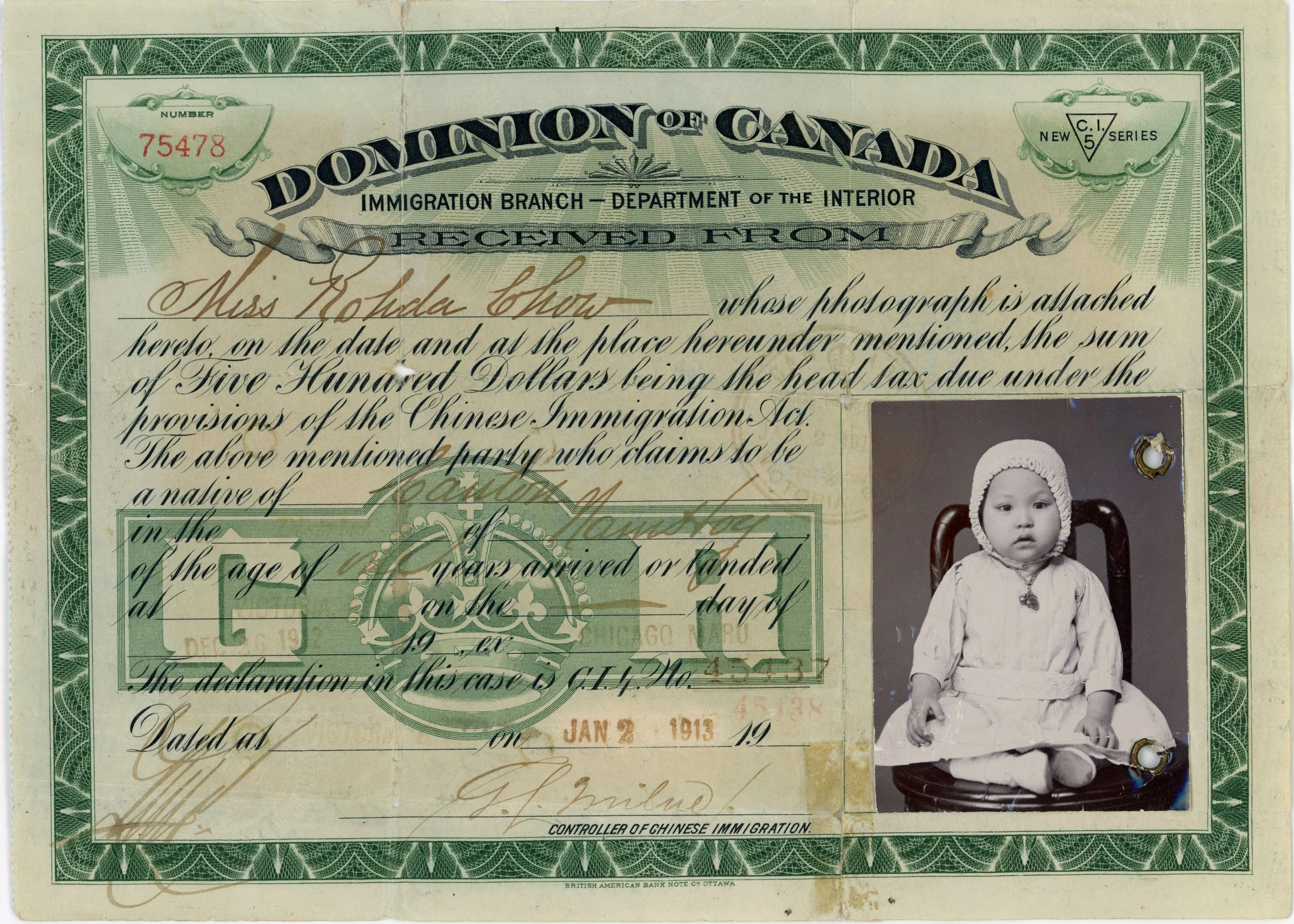

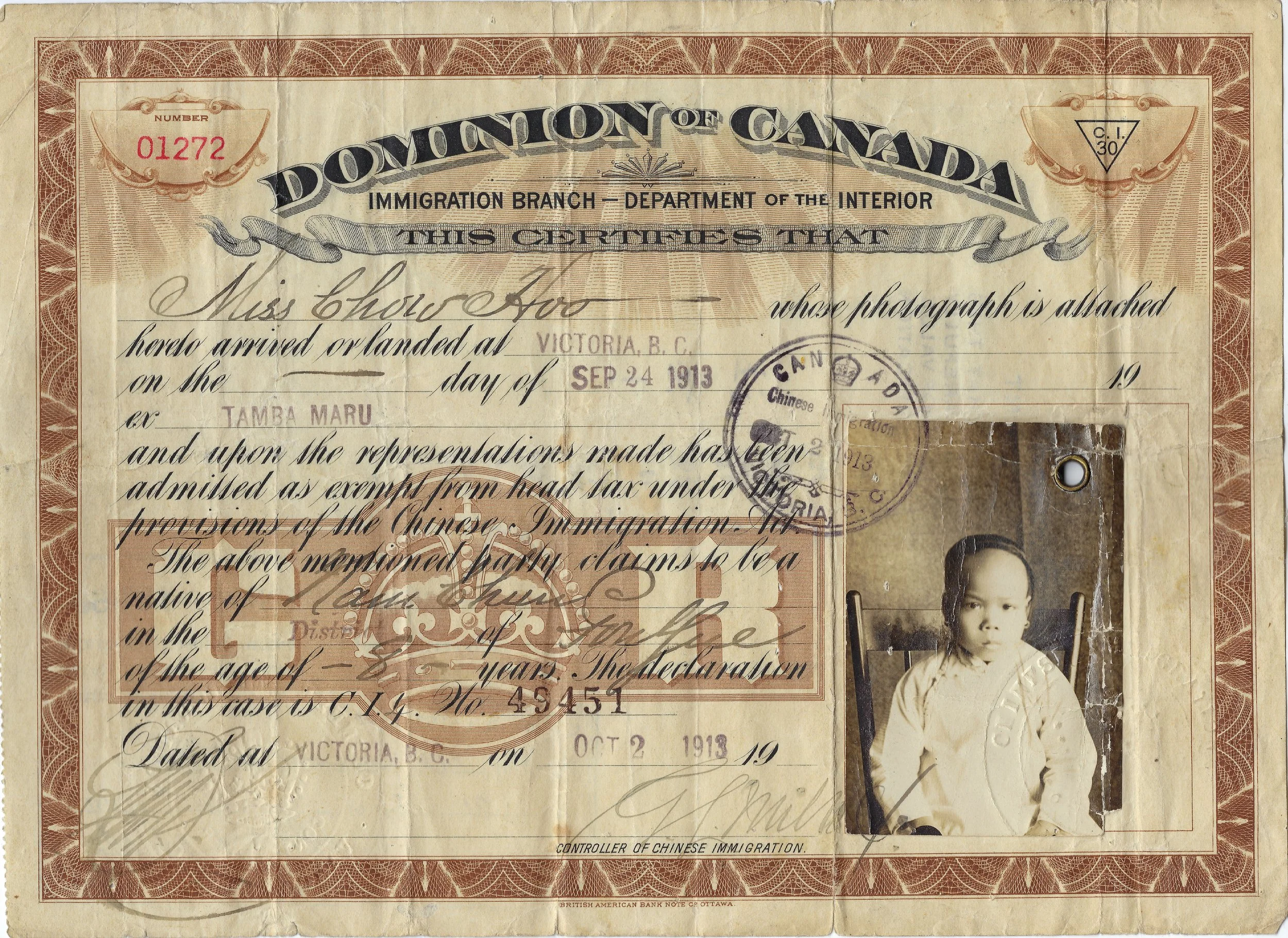

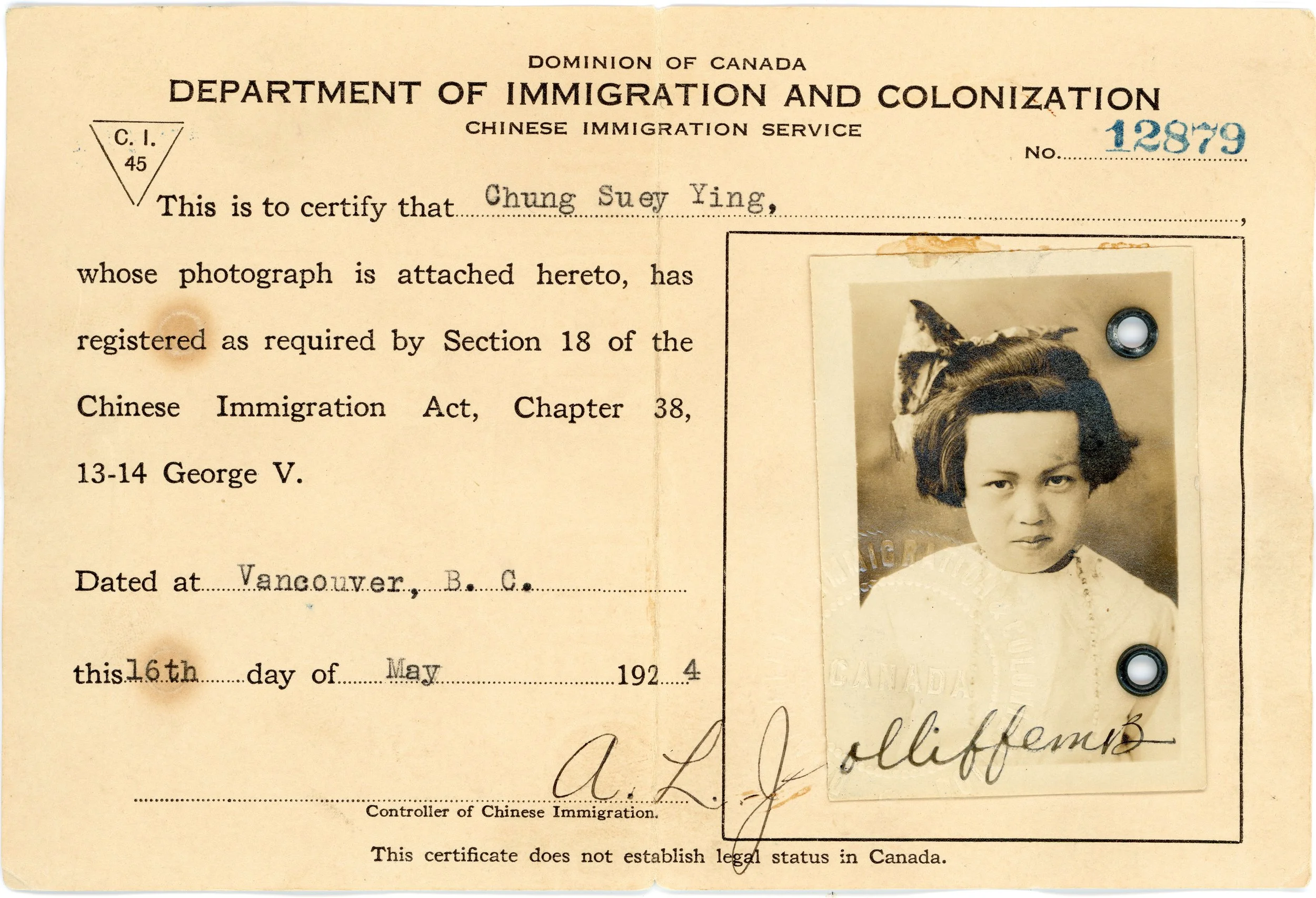

The families living in Coquitlam who contributed the following C.I. Certificates to The Paper Trail Collection (at UBC Library) and gave CHS the permission to reproduce them for our exhibition:

CHOW Hoo

CHOW Rohda

CHOW Rosey

CHUNG Suey Ying

WONG Bing Tong

WONG Lan Sin

Big shout out to the amazing team at Coquitlam Heritage:

Colton Enslen

D. L. Wang

Naomi Fong

Emily Zhang

Markus Fahrner

TIMELINE

-

The first Gold Rush in British Columbia occurs, drawing in many Chinese men in search of their fortune.

年--不列颠哥伦比亚省 发生了第一次淘金热, 吸引了许多华人前来寻 找工作机会。

-

Railroad construction began with Chinese labour brought in from Oregon and China.

加拿大开始修建太平洋 铁路,并从俄勒冈州和 中国引进华工

-

The first Chinese Immigration Act is enacted into law, instating a $50 head tax on any Chinese person entering Canada.

第一部《华人移民法》 正式颁布,规定对进入 加拿大的华人征收 50 加元的人头税。

-

The head tax is raised to $100 after the $50 tax proves ineffective at stopping Chinese immigration.

年--在 50 加元的人头 税被证明无法有效阻止 中国移民后,人头税被 提高到 100 加元。

-

The head tax is raised again, this time to $500 as the previous tax has not slowed immigration. This is about two years wage of a worker at the time.

年--由于之前的加税未 能减缓移民速度,人头 税再次提高到 500 加 元。这相当于当时一名 华工两年的工资

-

A series of riots break out in Vancouver’s Chinatown when the Asiatic Exclusion League march in the city. Tens of thousands of dollars in damage is done to Chinese and Japanese owned businesses.

排亚联盟(Asiatic Exclusion League)在温 哥华唐人街与小东京发起 暴动,引发一系列骚乱。 当时华人和日本人遭受了 数万加元的损失。

-

The 1923 Chinese Immigration Act, often called the “Exclusion Act” is passed into law, barring all immigration of Chinese people into Canada.

年--《华人移民法》(通 常称为 “排华法案”) 正式通过,除极少特例 之外,所有华人被禁止 移民加拿大。

-

World War II begins, the Canadian government begins to restrict the ability for Chinese immigrants to send money home to their family, limited to $25 a month.

第二次世界大战爆发, 加拿大政府开始限制华 人移民寄钱回家,每月上限为 25 加元。

-

Government conscription of Chinese Canadians. Many refuse to serve, divides are created in the community on whether to fight.

年--政府征召加拿大华 人入伍。许多人拒绝服 兵役,华人社区在是否 参战的问题上产生了分 歧。

-

Repealing of the 1923 Chinese Immigration Act.

废除 1923 年《华人移 民法》

-

Canada removes restrictions based on nation of origin.

年--加拿大移民政策取 消基于原籍国的限制

-

Canada begins a points-based immigration model, in an effort to create a fairer immigration system.

年--加拿大开始实行计 分制移民系统,寻求更 公平的移民决定方式。

A Brief History of Chinese Immigration to Canada, restrictions and exclusions

加拿大华人移民简史:限制与排斥

Significant immigration to Canada began with the 1858 gold rush, in the hope of a quick fortune many Chinese men living in California moved up North.

The next immigration wave occurred during the construction of the Trans-Canada Railway. Contractors hired thousands of workers from California, others were hired with the help of labour contractors directly from China. Most of these men hailed from Cantonese speaking areas. Contractors would pay them far less than their white counterparts. The Chinese men were often treated poorly, and were forced to do the hardest and most dangerous work.

The Chinese Immigration Act of 1885, the “head tax” law, legislated a $50 tax on any Chinese person entering Canada. The head tax would increase with time, eventually reaching $500 by 1903, this was meant to represent two years’ salary of a worker.

Despite the continual raising of the head tax, immigration continued, in part because companies would often pay the tax to bring workers into the country, keeping them indebted with a portion of their wage going to paying off the tax. At the same time Anti-Asian sentiments began rise, with many locals fearing that the cheap labour would threaten their jobs.

In 1923 the Chinese Immigration Act was passed. This act is often referred to as the exclusion act. It was only repealed in 1947, however, it wasn’t until 1962 that national origin restrictions were removed from Canadian Immigration Law. The act continues to have wide-reaching effects on Canada’s Chinese community.

-

加拿大首批华人移民潮始于 1858 年的淘金热。当时许多居住在加利福尼亚州的华人男性北上淘 金。

第二波移民潮发生在建设横贯加拿大的铁路期间。当时的劳务承包商从加利福尼亚州雇佣了数千名 华工,其他人则在劳务承包商的帮助下直接从中国大量招聘工人。这些人大部分来自台湾和广东。

华工所得到的工资—低于白人劳工。除此之外,这些中国人往往受到恶劣对待,被迫从事最艰 苦、最危险的工作。

1885年加拿大联邦政府颁布《华人移民法》,又被称为 “人头税 “法,规定对任何进入加拿大的华 人征收50加元的税款。随着时间的推移,这笔人头税不断增加,最终在 1903 年达到 500 加元, 相当于一名工人两年的工资。

尽管人头税不断提高,中国移民仍在继续,部分原因是雇主通常会支付人头税以将华工引入该国, 从而使他们落入债务陷阱,因为华工不得不将工资的一部分用来偿还税款。与此同时,加拿大的反 亚裔情绪高涨,许多白人担心廉价劳动力会威胁到他们的工作。

1923 年加拿大再度颁布新版《华人移民法》。该法案通常被称为《排华法案》。虽然该法案到 1947 年已被废除。但直到1962年,加拿大移民法方才真正取消了原籍限制。《排华法案》对加拿 大华人社区产生了广泛而深—的影响。

Workplace 工作场所

Following the cessation of construction on the railroad, many Chinese immigrants found themselves without work in an environment with increasingly racist feelings towards them. Most white businesses would not hire Chinese men, forcing them to create their own businesses.

One of the most common businesses started by Chinese men in the early 20th century was a hand-wash laundry. Laundry work was seen as undesirable and typically reserved for women. Laundries did not require a significant financial investment from their owners to start them up. In 1893, Vancouver legislated that laundries could not be opened outside of its Chinatown.

Laundrymen experienced a great deal of hardships. Racism was commonplace, white customers did not understand the characters printed on laundry tags, using it as an avenue to bully and harass. Media portrayals for many years have made heavily accented laundrymen the punchline of hurtful jokes. The 1907 Race Riots in Vancouver and other major cities saw Chinese-owned businesses attacked. This kind of destruction of property was not limited to the riots, however, with Chinese laundries being frequently targeted for robbery and other crimes.

Casual Chinese eateries could be found in the 1860s in Barkerville, BC. More established ones could be found in the 1890s in Vancouver’s Chinatown, and even earlier in Victoria’s Chinatown. The fare was often a mix of Western and Chinese foods. Chinese chefs were forced to adjust their recipes, with most dishes originating from Cantonese cuisine. These new meals combined Western tastes, and available ingredients, with Chinese cooking techniques.

-

在加拿大太平洋铁路修建完成之后,许多中国移民发现自己被迫失业。当时周围的环境对他们的种族主义情绪日益严重,大多数白人企业不愿雇用华人,这迫使许多华人自己创业。

在20 世纪初,华人创办的最常见的企业之一是手洗洗衣店。洗衣工作被视为不受欢迎的工作,通常只有妇女才能从事。但开洗衣店并不需要店主投入大量资金。1893 年,温哥华立法规定洗衣店不能开在唐人街以外的地方。

华人洗衣工饱受艰难困苦,种族歧视早已是司空见惯。例如白人顾客以不懂洗衣店标签上的文字为由,大肆欺凌和骚扰华人洗衣店。多年来,媒体对洗衣工的描述带有浓重口音的洗衣工成了广为流传的歧视笑柄。1907 年在在温哥华和其他大城市发生的排亚种族骚乱中,华人企业商铺屡遭袭击。然而这种破坏财产的行为并不仅限于暴乱,华人洗衣店也经常成为抢劫和其他犯罪的目标。

餐馆则是华人开设的另一个常见行业。加拿大第一家中餐馆于 1901 年开业。那时中餐馆的供应的菜肴通常都是中西合璧。除此之外,许多华人厨师选择对现有的粤菜食谱进行改良。这些菜肴将西方口味,现有食材,以及中式烹饪技术进行了完美结合。

Chinese Opera 粤剧

Opera theatres were one of the most important cultural aspects of the Chinese diaspora living in British Columbia. Several theatres operated both in Victoria and Vancouver. These places operated as the faces of the Chinese community, extending Chinese culture to Western people. They were visited by the thousands of Chinese people living in the Lower Mainland, seeking to experience their own culture in a place far away from home.

Chinese theatres have been in Victoria for as long as Chinese immigrants have, with the first cropping up around 1860.

The theatres had to contend with the head tax laws of the 1885 Immigration Act. Some theatres avoided head tax restrictions, by paying a $500 bond for actors. The bond lasted for six months but could be extended for up to three years.

Sabbath laws also hampered performances. Fines were issued to theatres for performing on the Sabbath, though theses laws were able to be circumvented. Chinese managers were able to convince the governing bodies that the shows were religious, a truthful statement for some plays, allowing performances to go ahead.

Despite these restrictions, theatres expanded, and new ones were built to accompany a growing Chinese community in Vancouver and Victoria. The theatres diversified their performances, offering vaudeville performances with white actors to draw in Western audiences.

Although anti-Chinese sentiment continued to grow during the early 20th century, the opera continued to have success with the community. One of the first stars of Vancouver’s Chinese opera scene was Zhang Shuqin, paid over six times the average salary of a performer. Crowds went so far as to pitch apples at performers thought to have wronged Zhang.

-

粤剧剧院是居住在不列颠哥伦比亚省的华人华侨最重要的文化活动之一,尤其是在维多利亚和温哥华。这些地方作为加国最大的华人社区的所在地,向其他族裔传播中国文化。成千上万居住在低陆平原的华人有幸到这些剧场观看粤剧演出,在异国他乡体验自己的文化。

维多利亚的华人剧院的历史与当地的华人移民的历史一样悠久,最早的剧院可以追溯到1860 年左右。

这些华人剧院必须遵守《1885华人移民法》中的“人头税”法。一些剧院通过为演员支付 500 加元的保证金来规避人头税限制。保证金期限为六个月,但可延长至三年。

除此之外,加拿大的安息日法(Sabbath Laws)也妨碍了剧院的运营。政府会对在安息日(周日)演出的剧院处以罚款,但在某些情况下该法律是可以规避的。因为华人剧院的管理者能够让管理机构相信演出是具有宗教性质的、因为对于某些剧目来说的确如此,只有这样演出才得以继续。

尽管有种种限制,加拿大的粤剧院不断扩大,新的剧院也随之建成,以满足温哥华与维多利亚日益增长的华人社区的需要。剧院的演出形式开始多元化,并聘用白人演员以及增添耍表演,以吸引不同族裔的观众。

尽管 20 世纪初的反华情绪持续高涨,但粤剧在温哥华和维多利亚仍然取得了成功。温哥华粤剧戏曲的首批明星之一便是张淑琴(音译),她的工资是普通演员的六倍多。当时的观众甚至向被认为得罪张淑琴的演员扔烂菜叶。

Archival photo of Yip Sang, 1845-1927, one of the patriarchs of Vancouver’s Chinatown. Handout The Vancouver Sun https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/canada-150/canada-150-yip-sang-the-unofficial-mayor-of-chinatown

Sending Money Back Home 寄钱回家

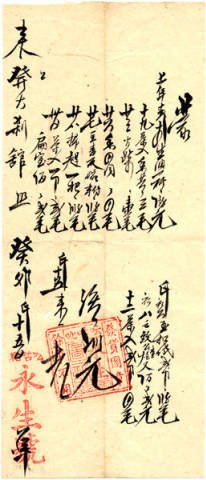

For most of the history of Chinese immigration, remittances, or money sent to relatives in China was handled by fi rms, alternatively, a trusted friend or neighbour returning to China could deliver money. There was a strong sense of trust and community accountability.

During World War 2 Canada began to require permits for money sent abroad, setting a maximum rate of $25 per month. The government also restricted who could handle money transfers, taking the authority out of the hands of local Chinese fi rms. This caused many, such as the Wing Sang Company, to deteriorate greatly as the practice of transferring money changed with the new regulations.

One could send more than $25, however, it required extensive permits to be filled out. The authority was placed in the hands of China’s Nationalist government, giving them agency over their diaspora, this allowed the Chinese government to further tax the diaspora. They were able to set the rates of exchange unfavorably, to profit themselves.

In theory, Chinese workers should have qualified for tax deductions since they had dependents, albeit in China. It took until 1942 for the deductions to come into effect.

By 1943, Canada began to pursue perceived tax fraud and rejecting tax deductions, with the government claiming their need to support dependents was unverifiable. Many Chinese Canadians lacked the necessary documentation, or legal support to pursue their claims. Racism made this even more difficult, as many held a bias that Chinese workers did not have dependents, and were lying to see reduced taxes, although a majority were married with families in China.

-

中国移民在大部分时间里,都是通过汇款公司给在中国的家人寄钱的。有时华人也会请返回中国的可信赖的故交帮忙转交钱款。当时的华人社区有一种强烈的信任感和社区责任感。然而,在加拿大政府残酷的战时政策极大地改变了汇款方式之后,这种信任消失了。

战争期间,加拿大开始要求向国外汇款必须申请政府许可,并规定每月最高汇款额为 25 加元。同时加拿大政府还限制了谁可以代理国际汇款,将权力从当地华人公司手中收回。这导致许多公司,例如永生公司,的经营状况大大恶化。

后来,个人汇款金额被允许超过 25 加元,但需要填写大量许可证与通过繁的手续。这同时也使中国国民党政府拥有了对海外华人对华汇款的代理权。这使得中国政府可以进一步向侨民征税,并制定不平等的汇率牟利。

从理论上来讲,历史上的华工应该有资格在加拿大享受减税资格,因为他们在中国有需要赡养的家属。但直到 1942 年,这项减税政策才在华人群体中开始生效。

然而到了 1943 年,加拿大以追查税务欺诈行为为由,拒绝为华人减税。联邦政府声称华人无法证实其有需要赡养人,因为许多华裔加拿大人缺乏必要的法律文件。种族主义使这一问题变得更加棘手,当时的政府对华人充满了偏见:他们毫无根据的认为华人没有受抚养人,他们撒谎是为了获得减税。事实上大多数华人已婚并在中国有家庭。

Force 136 men await in England for repatriation to Canada. Courtesy of the Chinese Canadian Military Museum.

World War II - The Home Front 二战 – 后方战线

Over 600 Chinese Canadians fought in the Second World War, many more would aid the war effort on the home front despite facing racism across Canada.

The Canadian government of the time pushed racist policies affecting many racial minorities. Ministers frequently did not look to nationality, but to race, when looking for potential enemies.

There was a reluctance among policymakers to allow Chinese Canadians to train for the home defense units or to join the military. They felt that if they were to give Chinese Canadians this opportunity, they would be able to lobby for enfranchisement after the war.

In the early war years Chinese Canadians were barred from serving in any branch of the military. Very few were able to bypass this restriction.

The community itself remained divided on whether they should volunteer to fight. Some felt that they should not serve a racist country, others however saw this as an opportunity to achieve recognition. By fighting, they hoped to claim citizenship. Chinese Canadians were in theory offered the same rights as anyone else. This however was not true in practice, it took many more years for race-based immigration policies to be dismantled, and even today, racism and discrimination are still felt in Canada’s Chinese community.

-

有 600 多名加拿大华人参加了第二次世界大战,另有更多的华人在后方协助战争。尽管当时他们在加拿大面临着各种各样的种族歧视。

当时的加拿大政府推行种族主义政策,这一举措极大地伤害了许多少数族裔。官员们不看国籍,只看种族,认为任何非英裔加拿大白人的人都是潜在的人。

根据种族主义观念,少数族裔被任意划分到不同的行业。例如,意大利裔加拿大人被安排从事重工业工作,官员们声称他们更适合这些工作。中国人、日本人、和原住民则被迫从事农业工作。

政府官员不愿意让华裔加拿大人接受部队的训练,更不愿意让华裔加拿大人参军。他们认为,如果给华裔加拿大人机会参军,华裔加拿大人就能在战后游说他们获得公民权。

战争初期,加拿大华人被禁止在任何军种服役,能够绕过这一禁令的人寥寥无几。

与此同时,在是否应当入伍参战的问题上,加拿大华人社区本身也存在分歧。一些人认为,他们不应该为一个种族主义国家服务。其他人则认为这是一个追求平等的机会。他们希望通过参战获得公民身份。二战后,加拿大华人在理论上享有与其他族裔同等的权利。但实际上并非如此,基于种族差异的殖民政策直到几十年后方才取消。即使到了今天,加拿大华人社区仍然能感受到种族主义和歧视。

Associations 会馆

Around 80% of the Chinese men living in Canada during the first half of the 20th century were married, with families at home in China. This lack of family support brought about an adaptation of traditional associations.

These organizations provided support and sought to help many of the people, many who came from rural lifestyles in China. They provided social services and housing support, particularly for older members of the community. These associations were often involved with banking services. Perhaps most importantly though, they provided friendship and camaraderie.

There were many types of associations in Canada, but their number continued to grow as immigration restrictions got tighter, they reached their peak during the years of the exclusion act. Six groups drew membership based on the town or city, this started in 1898, by 1937, there were 17. An even more dramatic rise is visible in associations based on shared surnames; there were 26 groups in 1923. A few years later, in 1937, there were 46 groups.

One of the most prominent was the Chinese Benevolent Association of Vancouver, founded in 1896. This group has been said to be the de facto government of Vancouver’s Chinatown. It was founded in part by Yip Sang. Yip Sang was a wealthy businessman and prominent community leader. He was able to use business and political connections in Canada and China to support the residents of Chinatown. One of his most important ventures was a remittance service.

-

20 世纪上半叶生活在加拿大的华人男性中,约有 80% 已婚并组成家庭。然而由于种种限制,华人男性难以将家人带来加拿大。在这种缺乏家庭支持的情况下,推动了华人会馆的兴起。

这些会馆为许多新来的华人移民以及社区中的中老年人提供支持和帮助,包括提供社会服务和住房。除此之外,这些组织同时也提供汇款服务。但最重要的是,它们提供友谊和陪伴。

加拿大有多种类型的华人会馆。随着移民限制的收紧,会馆的数量持续增长。在《排外法案》颁布后,这些组织的发展达到了顶峰。1898 年,加拿大共有六个同乡会馆。而到了 1937 年,这一数字达到了 17 个。另外以共同姓氏为基础的宗亲会在1923 年共有 26 个团体。几年后的 1937 年,这样的组织多达 46 个。

其中最著名的是成立于 1896 年的温哥华中华会馆(Chinese Benevolent Association of Vancouver)。有一种说法称该团体是温哥华唐人街事实上的政府,其创始人之一便是叶生。叶生是一位富有的商人和杰出的社区领袖。他常常利用在加拿大和中国的商业往来与政治关系来帮助唐人街的居民。叶生最重要的生意之一是汇款服务。

Bachelor Society 单身汉社会

The 43 Harsh Regulations was the name Chinese Canadians gave to the 1923 Immigration Act. Today, it is more commonly referred to as the exclusion act. While previous legislation heavily restricted family members through head taxes, some were able to come. This changed with the 1923 act. The clauses of the act forbade Chinese Immigration to Canada, except under very specific circumstances.

The lack of women and families was significant. There was a 28 to 1 ratio of Chinese men to women during the years of the immigration act. This created the so-called “Bachelor Society.” These men sent money back to China to support their families, yet were unable to reunite with said family. Yeung Sing Yew, who immigrated in 1923, did not meet his daughter until 1965. Yeung Sing Yew’s grandson, Dr. Henry Yu, recalls how his grandfather, was excited to finally be able to show off his family.

The lack of familial support was felt by many. Groups and clubs worked instead to help their members, with funds organized if people were injured, or needed a place to stay.

The exclusion act allowed individuals to leave Canada for a period, normally less than a few years. Some returnees sold their immigration documents, allowing someone else to enter Canada under their name. These are the Paper Sons, named as many of them entered as the “son” of an existing resident during the head tax era. Paper Son also refers to those who arrived on forged documents. While the true extent of these men can never be known for certain, it is estimated that some 11,000 men came to Canada as Paper Sons at some point.

-

《43 苛刻条例》是当时的加拿大华人对 1923 年《华人移民法》的称呼。如今,它更多地被称为《排华法案》。虽然之前的人头税对家庭成员移民进行了严格限制,但仍有一些华人能够将家人带来加拿大。1923 年的法案改变了这一状况。除了极少特例以外,该法案条款全面禁止中国人移民加拿大。

在如此情形之下,华人社区女性移民数量严重不足。在《排华法案》实施期间,华人男女比例为高达 28:1。这就形成了所谓的”单身汉社会”。这些男性华工把钱寄回中国赡养妻儿老小的同时,却不得不与家人隔重洋。1923 年移民来加的杨星耀直到 1965 年才见到自己的女儿。杨星耀的外孙余全毅博士(Dr. Henry Yu)回忆道:父女团聚之后他的外祖父时常兴奋地向大家炫耀他引以为傲的家人。

许多华人都痛感家庭关怀的缺失。但这却进一步推动了华人会馆的发展。如果有人受伤或需要住处,会馆会提供资金来帮助他们的成员。

《排华法案》允许个人离开加拿大一段时间,通常不超过几年。一些回流者则选择出售了他们的移民文件,允许他人以他们的名义进入加拿大。这些以他人身份移民加的人被称作”纸生仔 (Paper Sons)”,因为他们中的许多人是以”儿子”的身份换取人头税的减免方才进入加拿大。”纸生仔”也指那些持伪造证件抵达的人。虽然这些人的真实人数。虽然这些人的真实人数永无法确定,但据估计,大约有 11,000 人曾以 “纸生仔”的身份来到加拿大。

Daily Life

-

Teacup and Saucer

The history of tea and tea culture is very old and extensive in China. Tea, also called “cha (茶)”, is believed to have originated over 5,000 years ago. During the era of the Tang dynasty (618-907), dried tea cakes were roasted and ground before being brewed in hot water, occasionally alongside other herbs and fruits. By the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), tea began being processed in a dried and loose-leaf format before being steeped in boiling water inside a teapot.

-

Instruments

These are traditional Chinese instruments, they are commonly used in festivals, folk harvest events, traditional performances, and Lunar New Year celebrations. The traditional Chinese rattle drum, when spun, the beads swing and hit the drum, making a rattle-like noise.

-

Instruments

The cymbal’s pitch and sound run relative to its size, this pair of cymbals is small and easily held in each hand via the red ribbon.

-

Instruments

The traditional Chinese waist drum, also called “腰鼓 yāo gǔ”. The drum is attached to the waist via strap and is struck with either drumsticks or one’s hands, allowing greater maneuverability as the drummer dances during the performance.

-

Biscuit Tin

Macfarlane Lang & Co. originally began as a bread bakery in 1817. In 1885, they began to manufacture biscuits. The top of the tin’s lid shows a woman with two Pekingese dogs. The Pekingese is a type of toy dog, originating in China, and its namesake refers to the capital city of Beijing (often Romanized as Peking). Pekingese dogs often served as companion dogs.

-

Biscuit Tin

Peek Frean is a biscuit and confectionary manufacturing brand, owned by United Biscuits (UK). These biscuit tins depict Chinese figures and images without any association with Chinese manufacturers. Despite the racism towards Chinese people, Chinese imagery remained, and continues to be, a popular feature of advertising.

-

Abacus

The abacus is a calculation tool, often used for addition/ mathematics. Its frame-like structure allows the user to slide beads back and forth for calculations. The exact historical origins of the abacus are unknown, but it is believed to have early connections to regions within Eastern Europe and Asia. Before numerical notations were widely used and standardized, tools like the abacus were used for practical calculation. The earliest Chinese abacus dates to around 200 BCE, during the early Han Dynasty. The early Chinese versions were known as a Suanpan and differed slightly in the number of beads used. This may have been due to an origin in counting rods, an earlier form of accounting system.

-

Mah Jong

Mah Jong is a game of Chinese origin dating back to the mid to late 1800s. Due to its historical presence as a popular gambling game, the game’s reputation suffered controversy by association and was banned in 1949 by the People’s Republic of China. Played with four players, the goal of the game is to obtain a complete hand, being four sets and a pair of like tiles (for a total of 14), by discarding and collecting tiles. In the 1920s, the game was introduced to the United States.

-

Blue Willow Platter

This serving platter would have been part of a larger table ware set. The pattern was inspired by a traditional folktale about a pair of lovers. Produced in post-war Japan for export markets, this style of porcelain was designed by Western designers for Western tastes. Ironically Chinese people faced racism in Canada while tableware imitated Asian styles.

ALBERT’S FAMILY: A story of immigration

Albert’s Great Grandfather was a part of one of the earliest groups to immigrate to Canada from China. He had to prepare for a three month long journey by ship between China and Canada, with no way of knowing when or if he would be able to return to his family in China, so he had to leave knowing that everything was in order. As was the case with many others, he ensured that he had a male heir before leaving. He also set aside 300 silver coins, a fund for his family to live off until he could begin work in Canada and then send them more money.

The quote speaks to the horrifying uncertainty and danger lying ahead of the journey. The Great Grandfather’s fear that he might never return instilled in him the need to have a heir to carry on his family line.

-

亚伯(Albert)的曾祖父是最早从中国移民到加拿大的人之一。当时中国和加拿大之间的旅程需要整整三个月。亚伯的曾祖父不知道自己何时或能否回到家人身边,因此离开前他不得不做好万全的打算。和其他许多人一样,亚伯的曾祖父在赴加前确立了一个男性继承人,并预留了300 枚银币。这笔钱将作为家人的生活费用,直到他可以开始在加拿大工作,并给他们寄更多的钱。

The Long Journey 长途跋涉

The journey was not easy, Albert’s Great Grandfather boarded a fishing vessel for the months long journey, they travelled with many stops to resupply the 100-ton boat. They first stopped in Korea, then Japan, Russia, up to Alaska, before finally arriving in Nanaimo. The trip was harsh, anyone who fell ill would be left at the next stop, to avoid the illness spreading to the rest of the passengers and crew. From there he travelled to Victoria to start work on the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

-

亚伯的曾祖父终于踏上了开往加拿大船只,开始了几个月的长途旅行、为了给这艘重达 100 吨的船补给,他们在旅途中停靠了很多次。先在朝鲜停留,然后到日本、俄罗斯、阿拉斯加,最后到达纳奈莫。船舱条件极其艰苦,病人会在靠岸补给时被抛下,以避免疾病传染给其他乘客与船员。亚伯的曾祖父从纳奈莫辗转维多利亚,随后投身于加拿大太平洋铁路的建设工作当中。

Albert’s Grandfather and Grandmother with his second uncle sitting in between them. Behind, from right to left: father, mother, aunt.

Working on the Railroad 建设铁路

Albert and the other Chinese workers lived in the mountains, working on constructing the railroad across Canada. They had to live sparsely. If one fell ill, they made use of local herbs and traditional techniques to make medicine. Albert’s Great Grandfather had some chickens, so he was able to eat eggs with his rice on occasion, a welcome addition to an otherwise plain meal. Money was sent home to family with the occasional return trip by one worker. Normally this was a trusted friend or neighbour from their home in China who could transport the money home.

Finding a New Job 另谋生路

After construction of the railway was completed, he was able to bring his son, Albert’s Grandfather, to Canada too, paying for his head tax with some of the money he had earned. Albert’s Great Grandfather lived in Victoria, working as a gardener for a high ranking official in the city. He lived in a small building on the property. His boss was an alcoholic, and frequently yelled at him, kicking him out several times. When he retired, he returned to his family in China, building a large and secure house to prevent any theft or kidnapping by bandits.

“他学到的第一个英语单词就是‘你这个天的(God damn you)

First English word he learned was God Damn You!”

-

在加拿大太平洋铁路建成后,亚伯的曾祖父把他的儿子,即亚伯的祖父。也带到了加拿大。亚伯的曾祖父用修铁路赚来的工钱替他儿子支付了人头税,父子二人随后定居在维多利亚。曾祖父在当地的一位高官家中做园丁,并被安排住在一处小屋里。虽身居高位,曾祖父的雇主却酗酒成性,并常对他大吼大叫,甚至好几次把他赶了出去。退休后,亚伯的曾祖父回到了中国,并在家乡建了一栋安全的大房子,以防匪盗。

-

为了修建横跨加拿大的铁路,亚伯的曾祖父与其他华工不得不住在遥的山区。华工们的生活条件极其简朴。如果生病了,他们只能用当地的草药结合传统中医制药工艺来治疗自己。亚伯的曾祖父养了几只鸡,所以他偶尔能吃到鸡蛋。这对原本平淡无奇的伙食来说,是一种令人欣喜的加餐。华工们会将工资交给一位工友带回家中,以支持他们在中国的家庭。这个责任重大的工友通常是可信赖的同乡故交。

Albert’s sister in front of the fort house, building built with imported materials, bought with the money that great-grandfather brought back to China.

Developing Skills 影相馆

Albert’s Grandfather was able to have an education in China before arriving in Canada, he opened a photo studio in Victoria, B.C. Albert’s Grandfather was able to travel back and forth much more easily than his father, owing to improvements in ship technology. This upset Albert’s Great Grandfather, who was unable to go back and forth due to extremely long and dangerous journeys. Due to being able to travel back and forth, he was also able to have multiple children, as opposed to the single child that many of Albert’s Great Grandfather generation had.

-

亚伯的祖父曾在中国接受过教育。在来到加拿大之前,祖父在家乡开设了一家照相馆。在今天,摄影随处可见。但在当时,摄影师还是一个高

深复的职业。由于船舶技术的进步,亚伯的祖父比他的父亲更容易往返于中加之间,这让亚伯的曾祖父颇有些嫉妒。因为他的曾祖父年轻时所经历的旅途是漫长而危险的。由来回旅行更为便捷,亚伯的祖父还能诞下多个孩子,而不是像亚伯的曾祖父那样只有一个孩子。

Returning 归加异途

Albert’s Grandfather attempted to bring his wife to Canada during the early years of the 1923 immigration act, however, he was refused multiple times. Deciding he wanted to be with his family, he returned home to China. Albert was able to move to Canada in 1984, sponsored by his sister who had started a business in Canada some years prior, it was during these years that many other family members of his were able to come to Canada too with the help of his sister and her husband. Albert’s Great Grandfather and Grandfather could not settle in Canada due to the discrimination they faced at that time, however the third generation of the family eventually made Canada their home. Albert’s family history reflects the resilience of the Chinese Canadians.

“我的祖父曾试图将我的祖母带来加拿大,但不幸的是,当时加拿大出

台了《排华法案》

My grandfather tried to apply for my Grandmother to come to Canada, but unfortunately at that time the Chinese exclusion act came into being.”

-

亚伯的祖父曾在1923 年《排华法案》实施初期,多次尝试将妻子带到加拿大。但他却多次被拒。最终亚伯的祖父决定与家人待在一起,为此他不得不回到中国。

1984 年,亚伯在他姐姐的担保下移居加拿大。当时亚伯姐姐一家已在加拿大经商多年。正是在这些年里,亚伯的许多其他家人也在他姐姐姐夫的帮助下来到了加拿大。