Riverview:

an artist’s point of view

CONTENT

WARNING

The exhibition contains text, images, and artwork which may be disturbing to some visitors. The exhibition contains descriptions of mental health treatments, equipment and medical language and terminology no longer used today. Some treatments are today considered inhumane and ineffective.

Not too long ago when people were labeled as “mad” they were considered no longer suitable for society. The French philosopher Foucault wrote in his book History of Madness that anyone who steps off the accepted path is condemned and is subjected to physical expulsion from normal life.

Essondale Hospital interior recreation lounge C5-S01-SS02-EH.009

Societies rejection of so-called “mad” people frequently came with a moral condemnation as well. The state of people’s mental health was also linked to population control and the concept of working or being a productive member of society. The move from an agricultural society to an industrialized society demanded a large pool of workers. With increased urbanization, and a frequently impoverished working-class; governments felt an increased need to control their populations. Industrialized work demands strict time routines and requires a dedicated work ethic. Unruly non-conforming behaviour can be seen as a threat to the social order. Workhouses and asylums became places for people deviating from the supposed standard or norm.

Over many years women’s health has and continues to be mostly neglected because the male body is seen as the standard. Hysteria was commonly diagnosed in women. Interestingly enough the word Hysteria stems from Hippocrates a Greek word from the 5th century BC meaning the disease as located in the uterus (Greek hysteron).

The United Nations Population Fund mentions that as late as 1950 female genital mutilation (clitoridectomy) was practiced in Western Europe and the United States to treat perceived ailments including hysteria, epilepsy, mental disorders, masturbation, nymphomania and melancholia.

Today society has developed a more nuanced and kinder view on mental health. Currently, ideas are more centred on integration and moving away from an arbitrarily supposed standard.

Institutions like Riverview and others are a reflection of societies’ changing attitudes on how people with mental illness were treated or what was regarded as an illness. Institutions and how they treat patients reflect problematic attitudes like eugenics and scientific understanding of mental health. What happened in Riverview, the treatment of patients is an expression of society’s wider of mental health.

Essondale interior laboratory C5-S01-SS02-EH.012

APRIL 1ST, 1913

The hospital for the Mind at Mount Coquitlam opened in Essondale. soon, the name changed to the Essondale hospital. it wouldn’t be until 1965 that the name changed to Riverview hospital. it would keep this name until the summer of 2012 when it finally closed.

The first building was the Male Chronic Wing built in 1913, with spots for 340 patients. By the end of 1913 however, it held 453 patients, marking the beginning of the overcrowding that would plague the hospital for years to come. Three years later, in 1916, there were 687 patients. It wouldn’t be until November 1st, 1924, that a second building, the acute Psychopathic Unit with a capacity of 300, opened.

Pathology room, East Lawn, Coquitlam archives C5.009

More buildings followed, and in 1922, the Boy’s industrial school at Coquitlam (BISCO) opened. this school held 69 boys and 24 staff, confined to the relative isolation of Essondale. it was an early attempt at juvenile reform, with all the boys sent to BISCO for breaking the law. in 1935, these buildings would be converted into a home for the aged, after new legislation required the operation of a provincial home for the elderly; which eventually opened in 1936.

Boys industrial school at Coquitlam Cottage 2, Coquitlam archives C5.052

The Crease Clinic had new operating facilities, which allowed for the performance of lobotomies, beginning in 1949. This treatment severed neural pathways to the prefrontal cortex to treat schizophrenia, anxiety, and depression. In 1951, 50 of these procedures were performed, it was only in 1954 that the procedure would lose favour. Other invasive and inhumane procedures regularly took place at the hospital. Other procedures included shock therapy, also known as Electro-Convulsive therapy, or ECT, and insulin Coma treatment. ECT involves the administration of electrical shocks, up to three times a day. In 1950, 413 patients were receiving treatment daily. It was used to treat mania, bipolar disorder, and other conditions. It was initially used without anesthetic. Insulin Coma Treatment was commonly used for schizophrenic patients. It involved overdosing the patient with insulin to trigger convulsions and coma.

It wouldn’t be until the 1980s that mental health care switched its focus to rehabilitation and placing people back into the community.

Tuberculosis struck the hospital in 1951, with over 200 affected. X-rays were used to attempt to catch the disease earlier but the problem persisted. In 1955, the North Lawn building opened to treat patients with TB.

Treatment options began to improve in 1950 with Pennington hall opening, offering recreational therapy. Activities included board games, tennis, bowling, swimming, and dancing. By 1954 Chlorpromazine was introduced, the first anti-psychotic. This drug largely replaced ECT, Lobotomies, and Insulin Coma treatments.

OCTOBER 1930

The Chronic Female wing for 500 female patients opened. the building also served as a residence for the nurses and the new nurses training school. It began as a two-year course, with the first class graduating in 1932. From 1933 to 1951, however, it became a three-year course, reverting to the two-year program in 1952.

Many early pioneers of the study of mental health viewed women as inferior. Male doctors frequently failed to understand women’s physical and mental health. Many believed that women had a physical and mental need to be in the home; as such, women who deviated from this role were seen as mentally ill.

Women were checked into mental institutions by husbands or fathers. Post-partum depression was a common admission during Riverview’s operation. Hysteria was a common diagnosis for and mental illness suffered by a woman. The term remained in medical use until 1952. The most extreme treatment involved the removal of sexual organs.

Women were also the targets of eugenics driven treatments popular at the time. In the Essondale hospital, 200 sterilizations were carried out between 1933 and 1936. Most of those sterilized were women. Medical thought at the time was that mentally ill women were unfit to be mothers, and that they should not be allowed to pass on their genetics to the next generation.

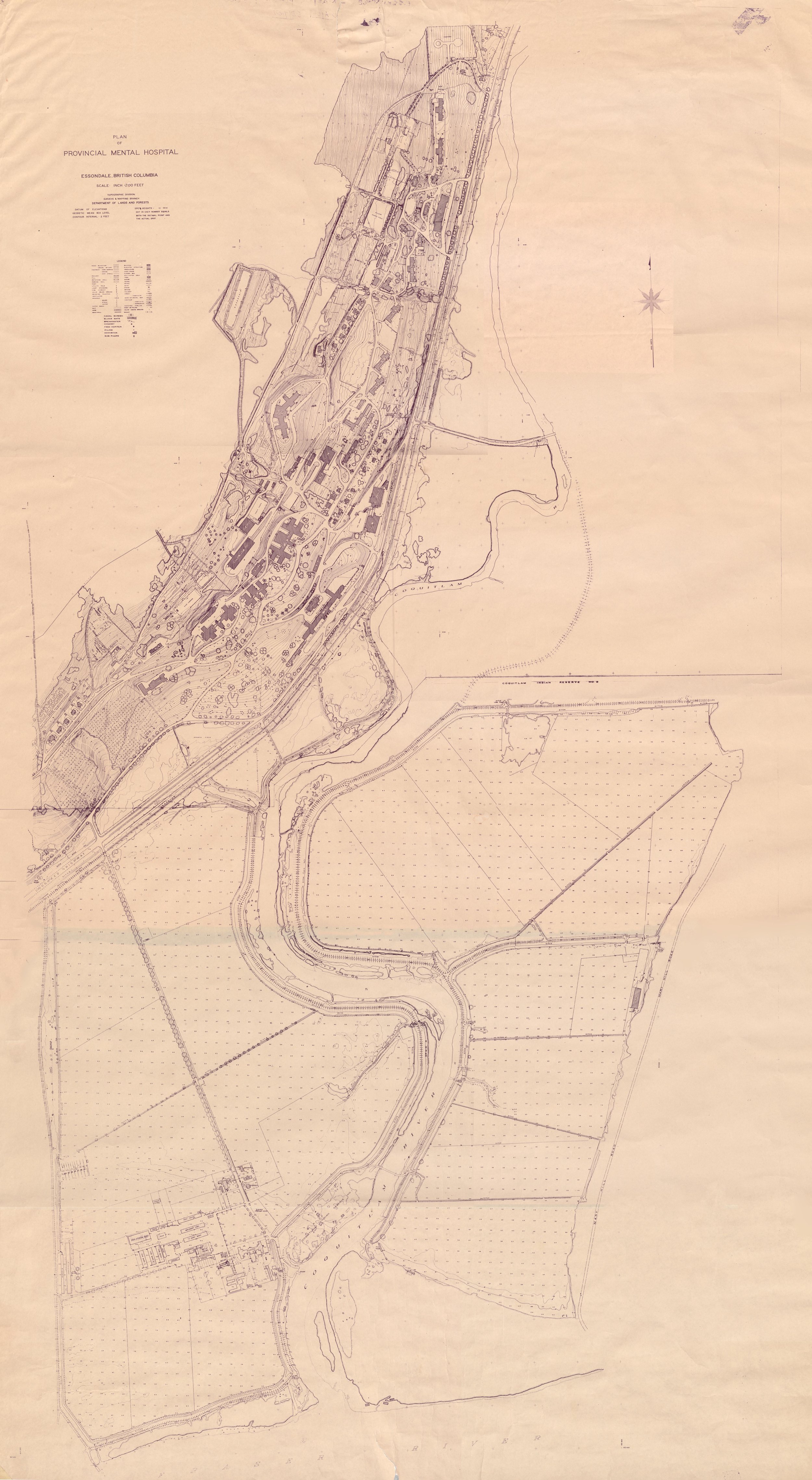

Colony Farm exists on the traditional territory of the Kwikwetlem people. After the colonization and subjugation of Indigenous peoples took place, and the reserve system was established in the mid-1850s, the Kwikwetlem were granted two small pieces of land, Reserve 1, or slakəyánc, was located just South of what would become Colony Farm in the area where the Coquitlam River meets the Fraser. The ditch around Colony Farm isolated slakəyánc, except for a small path leading into the reserve. The farm buildings and accommodations of Colony Farm were built near to slakəyánc, to the West.

Aerial view of Essondale grounds, Pitt River, and Fraser River, Coquitlam Archives C5.3768

In 1911, John Davidson became BC’s first Provincial Botanist. It was Davidson who to developed the gardens at Essondale. The initial objectives of the site were to study the province’s plants and develop accurate names for them. Much of this work was done by patients at Essondale as part of their occupational therapy.

The garden also contained a nursery that grew trees to be sent to many public places across the province. The gardens, were relocated to UBC in 1916.

Essondale - Construction of main buildings, Westholme Lumber Co. C5-S01-SS01-GN135

Colony Farm, located on the same grounds, was a site of cultivated land that grew food for the hospital. It was overseen by Mr. Charles E. Doherty, the Medical Superintendent of BC. Work on this farm was also done by patients of the hospital. Accommodation was provided in temporary buildings on the site.

In 1920, Colony Farm was recognized as one of the best farms in not only BC, but all of Western Canada. It produced most of the hospital’s food. Pigs and dairy cows were available, as well as a canning facility. Some of the produce grown included grains, pumpkins, turnips, celery, onions, beets, rhubarb, lettuce, and corn.

Collage, Colony Farm - Out buildings and cows, Coquitlam Archives C5-S01-SS01-GN46

The 1964/65 BC Mental Health Acts shifted the focus of mental health care to local facilities. Deinstitutionalization had begun, with upwards of 30 smaller facilities opening by 1970. Over the coming years, the availability of drugs and the rising costs of maintenance led to the closing of more and more beds at Riverview Hospital. By 1981, there were only 1,100 beds left out of 4,100. Further downsizing programs would take place, with the last patients leaving in 2012.

Dormitory, Coquitlam Archives C5.010-16

Drugs first arrived in large amounts during the 1980s and Expo 86. Dealers began to market high purity drugs to the increased tourist traffic. Police attempted to crack down on the drug use and prostitution cropping up in the neighbourhood, but the issues persisted. Around this time, de-institutionalization was ongoing in BC; many patients forced out of the Riverview Hospital made their way to the Downtown Eastside, in need of the historically affordable housing there.

The Downtown Eastside, often shortened to DTES, or referred to as Hastings, or East Hastings, is a historic neighbourhood in the city of Vancouver. The Downtown Eastside is a diverse neighbourhood home to several thousands of people. Currently, the neighbourhood is the site of an ongoing addiction and mental health crisis.

Throughout the late 80s and 90s, drug dealers preyed upon the vulnerable mentally ill people who had been forced out of mental institutions. This only furthered the issues that these people faced. Today, the Downtown Eastside continues to be a hotspot for mental issues and drug addiction. People are continually drawn for affordable housing and the concentration of mental health and addiction services.

The Great Depression and the Second World War had dramatic effects on the hospital. From 1934 to 1946 the patient population rose to around 4,100. Many nurses left to aid in the war effort, making the burden of overcrowding worse. In 1942 new regulations were created to make staffing easier. Married women were allowed to apply for jobs and auxiliary positions.

Corridor connecting Wings of Chronic Building, Coquitlam Archives C5.010-10

Following World War Two, a huge influx of veterans added to the overcrowding. The largest building at the time, East Lawn, had a maximum capacity of 921, in 1949 it held 1,445 patients. The Crease Clinic, in construction since 1929, was opened as a short-term veteran care unit. The building opened under the Mental Hospitals Act which allowed patients to voluntarily admit themselves and terminate their stay. Veterans receiving treatment here lived in accommodations on the nearby Colony Farm.

May Headridge standing and saluting in uniform 1937-43, Coquitlam Archives C5.130

Provincial Mental Hospital Graduation Class, Essondale, B.C. 1936, Coquitlam Archives C5.035

RIVERVIEW:

AN ARTIST’S POINT OF VIEW

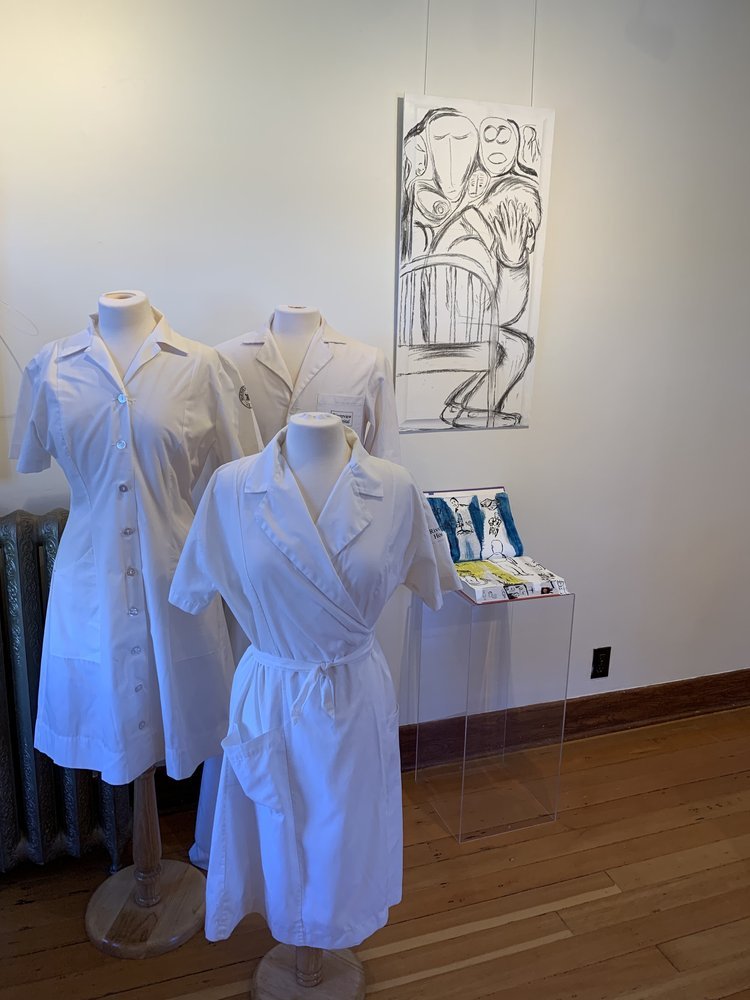

Artists Nadine Flagel, Haley Perry, Camila Szefler, Lolu Oyedele, Markus Fahrner, and Naomi Fong approach themes of mental health, physical separation, and the history of the Riverview Hospital through a range of media ranging from illustration, reclaimed textiles and drawing. The artists' works engage with individual Riverview objects within the CHS collection, and the history of Riverview to create a very intimate approach to mental health and the physical space of the hospital. See their work below.

TIME, MEMORY AND OBJECTS BY HALEY PERRY

Memory is experienced as abstract, internal, and formless; from the frustration of failed recollection, to the spark of finding that sought moment from the past. However if objects can connect us to the past, does that mean memory can live outside ourselves? Do objects represent memory in static physical forms?

These mix-media drawings explore the significance of objects and the way they hold memory. Treasured objects are coveted and adored. My chosen objects, a bed pan, surgical basins, and an ashtray: these are all functional items, and are far from being treasured. There are dark, unknown moments from the past they hold that can only be imagined through the context of the past they reflect; shining within the metallic surfaces. And in the present moment, reflecting back on us, we can question what these objects saw.

ARTIST BIOGRAPHY

Haley Perry is a settler artist living on the traditional lands of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) people. They graduated from Emily Carr University of Art + Design with a bachelor’s degree in illustration, and are currently working as an art teacher in Burnaby.

After graduation their artistic pursuits have included an array of gallery shows, editorial illustration work for magazine publications, art festivals and markets, private commissions, and a dedication to personal work.

You can find Haley’s work across social media at: @carnivorousart and through their website at www.haleyperry.me

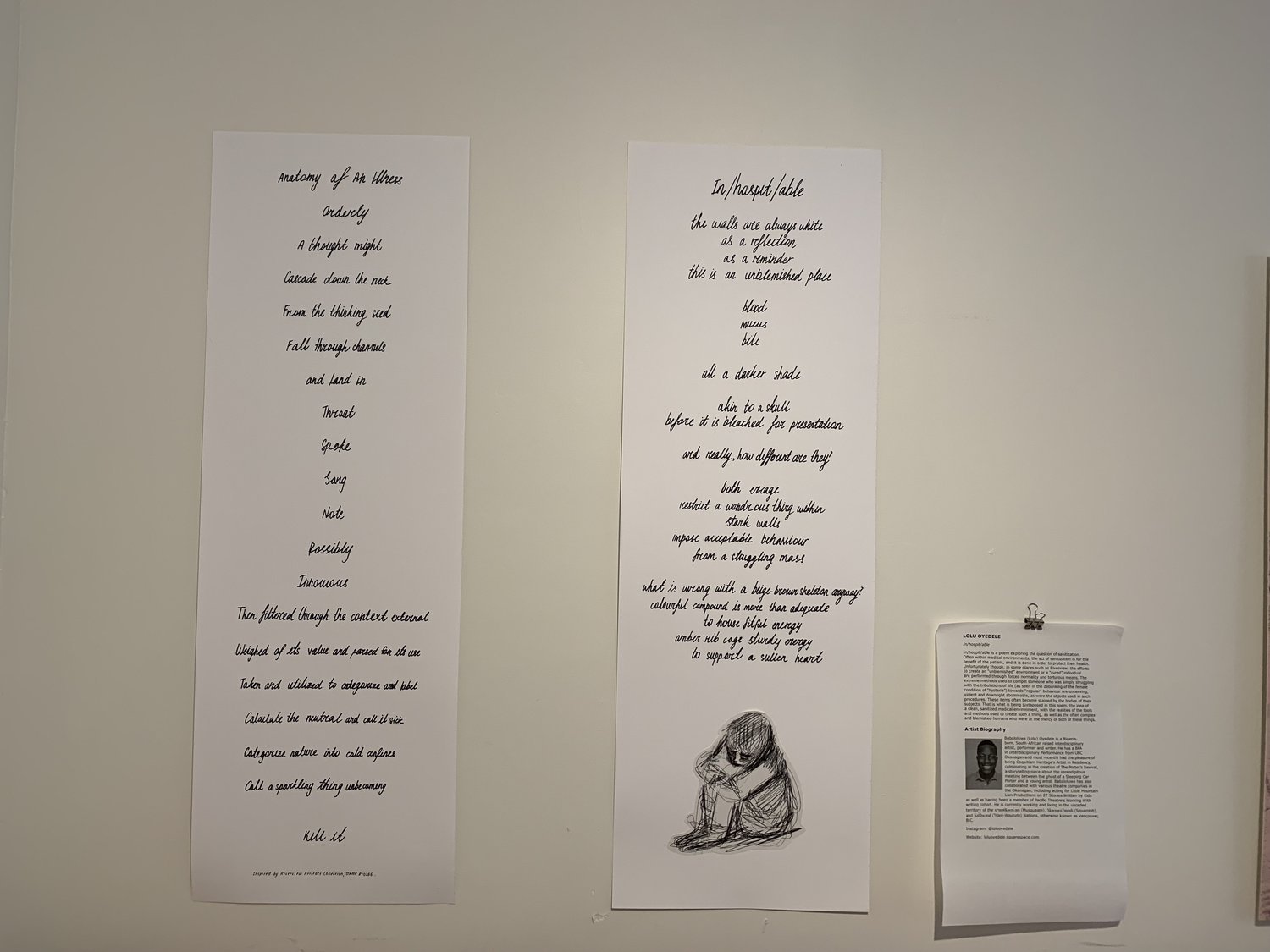

IN/HOSPIT/ABLE BY

LOLU OYEDELE

In/hospit/able is a poem exploring the question of sanitization. Often within medical environments, the act of sanitization is for the benefit of the patient, and it is done in order to protect their health. Unfortunately though, in some places such as Riverview, the efforts to create an “unblemished” environment or a “cured” individual are performed through forced normality and torturous means. The extreme methods used to compel someone who was simply struggling with the tribulations of life (as seen in the debunking of the female condition of “hysteria”) towards “regular” behaviour are unnerving, violent and downright abominable, as were the objects used in such procedures. These items often become stained by the bodies of their subjects. That is what is being juxtaposed in this poem, the idea of a clean, sanitized medical environment, with the realities of the tools and methods used to create such a thing, as well as the often complex and blemished humans who were at the mercy of both of these things.

ARTIST BIOGRAPHY

Babaloluwa (Lolu) Oyedele is a Nigeria-born, South-African raised interdisciplinary artist, performer and writer. He has a BFA in Interdisciplinary Performance from UBC Okanagan and most recently had the pleasure of being Coquitlam Heritage’s Artist in Residency, culminating in the creation of The Porter’s Revival, a storytelling piece about the serendipitous meeting between the ghost of a Sleeping Car Porter and a young artist. Babaloluwa has also collaborated with various theatre companies in the Okanagan, including acting for Little Mountain Lion Productions on 27 Stories Written by Kids as well as having been a member of Pacific Theatre’s Working With writing cohort. He is currently working and living in the unceded territory of the xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations, otherwise known as Vancouver, B.C.

Instagram: @loluoyedele

Website: loluoyedele.squarespace.com

BEND OVER AND THE PSYCHOLOGY TEXTBOOK BY MARKUS FAHRNER

For the piece Bend Over, I have chosen a Charcoal stick and as canvas a board from an old bed. The figure on the bed is bent over in agony, pressed down by dreams or perhaps people. I wanted to express the complex and multiple pressures people are exposed to every day.

The second piece is called The Psychology Text Book Similar to the first piece it deals with the many pressures people face. But it also speaks to the dangers of medicating. Sometimes we need to face certain issues in our life and perhaps need to find other ways to deal with or incorporate certain issues into our life and our identities.

ARTIST BIOGRAPHY

Markus Fahrner is the exhibition manager at Coquitlam Heritage Society, living on the unceded, occupied, ancestral and traditional lands of the Kʷikʷəƛ̓əm (Kwikwetlem), qiqéyt (Qayqayt),xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), Stó:lō and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations.

Markus is also a graphic designer and book artist. As a graphic designer he has worked on packaging design, created AIDS awareness ads in Uganda, created book and magazine layouts, and for a short while worked in the Ad department of the TriCity News. His artist books can be found in the collection of the Library of Congress Washington DC, Meermanno, Den Haag, Klingspor Museum Offenbach. He frequently writes his own texts and is currently exploring how to make inks from roots and berries found on his foraging trips. You can find more about him on Social media @fahrnerdesignworks

THE FAMILY REQUESTS OBJECTS IN LIEU OF MEMORIES, PLEASE BY NADINE FLAGEL

Inspired by Coquitlam’s Riverview Collection, I consider what a patient-centered, art-based, alternative history of Riverview might look like. My approach is informed by Mad Theory, a perspective that recovers the insights and experiences of (often gendered, racialized, colonized, othered) people who do not conform. Mad Theory respects the full humanity and knowledge of those deemed “mentally ill.” In the title, I alter a common line from obituaries to suggest a question at the heart of archival efforts: while the archive overflows with information, what does the archive not tell us?

My entry point is my grandmother, who was a patient at Riverview Hospital for nearly thirty years. Multiple stigmas of incarceration and mental disruption as well as geographic distance effectively erased her from day-to-day family life and from the awareness of some grandchildren. However, her position as incarcerated subject is not definitive: she was also a social spark, talented hairdresser, strong swimmer, loving mother, and talented maker with textiles. My personal goal is to reciprocate her making practices by creating textiles for her and to restore contact with her descendants in installation pieces that bring the institutional asylum of Riverview and the domestic space of Mackin House into tension.

ARTIST BIOGRAPHY

Nadine Flagel is a self-taught fibre artist whose mission is making art out of “making do.” Her artistic practice centers on the reuse of worn clothing, most often in quilts and hooked rugs. At their core, rug hooking and quilting are labour-intensive acts pulling together elements that were not originally designed to be side by side into new juxtapositions of texture, colour, and form, generating new meanings.

Flagel recently held her first two solo exhibitions in the Pacific Northwest. She publishes articles on art, teaches fibre art at Maiwa School of Textiles and community centres, has received grants to make art with youth, and has collaborated on a public art commission in Richmond, BC. She is a member of CARFAC and Craft Council of BC. A Vancouver settler, Flagel gratefully acknowledges that her life and work are made possible by the stewardship by the Skwxwú7mesh, səlilwətaɁɬ, and xʷməθkʷəy̓əm peoples of this unceded land.

You can find Nadine Flegel online at: www.nadineflagel.com/

Instagram: @nadine.flagel.artist

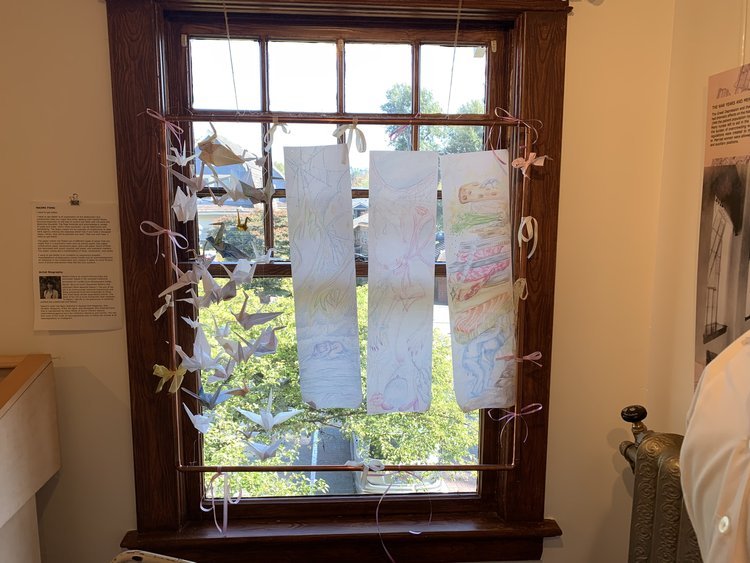

I WANT TO GET BETTER BY NAOMI FONG

I want to get better is an exploration of the destruction and construction that one might face when dealing with mental illness, focusing especially on the loss of control one feels with intrusive and distortive thoughts. The flags illustrate and acknowledge a variety of webs and traps, which when ensnared, can be destructive and debilitating. The paper cranes are an example of construction to take back agency echoing the Japanese belief that if one folds a thousand paper cranes, they will be granted one wish. That one wish here: I want to get better.

The paper cranes are folded out of different types of paper that one might find in a psychiatric ward such as printer paper, wax paper, construction paper, parchment paper, and craft paper. Some of them are decorated with pencil crayons, salt water, and washable markers. The paper cranes are a manifestation of hope, compulsion, and prayer.

I want to get better is an invitation to experience possible manifestations of destructive mental health and an acknowledgement of resilience in the construction and creation it takes to move forward even if divine intervention feels like the only solution.

ARTIST BIOGRAPHY

Naomi Fong is an award-winning artist and storyteller based in the unceded traditional territories of xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musequeam Indian Band), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish Nation) and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil Waututh Nation.) The aim of her art is to communicate personal experiences and bring emotional truth and awareness to those who have faced similar stigmatized events. The style of her art is more humanistic than aesthetic. To Naomi, real life is not glamorous or perfectly crafted but unadorned and flawed.

Naomi’s work has been featured in Applied Arts Magazine, Star Monthly Magazine, ATB’s Art Vault, and Renegade Arts Entertainment. She is represented by Essie White at Storm Literary Agency (stormliteraryagency.com) for children’s literature and comics. You can find more of her work at naomispractice.com or follow her stories at @naomispractice on Instagram.