Working the Green Chain:

Sikhs, Fraser Mills & The lumber industry

Sikhs and other South Asians have been in British Columbia for over 100 years. They have played vital roles in the economic, social, and political history of this province. They came in search of opportunity and a better life, working in farming, fishing, and for the railways, but many first gained a foothold here by working in the lumber industry. Fraser Mills, Coquitlam, employed many of these men. Some eventually returned to India, some moved on to start their own successful companies, and some stayed in the area. Their families are still here today. They have served in the military, contributed to the province’s businesses and education, and were instrumental in creating a better society.

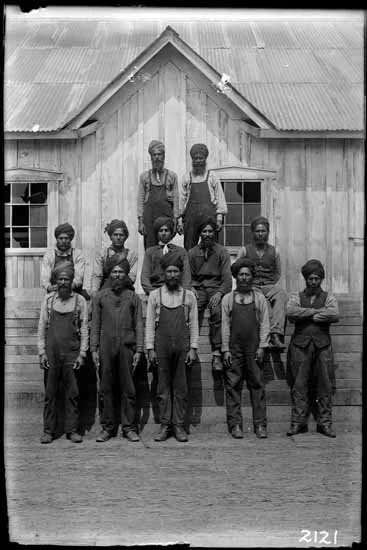

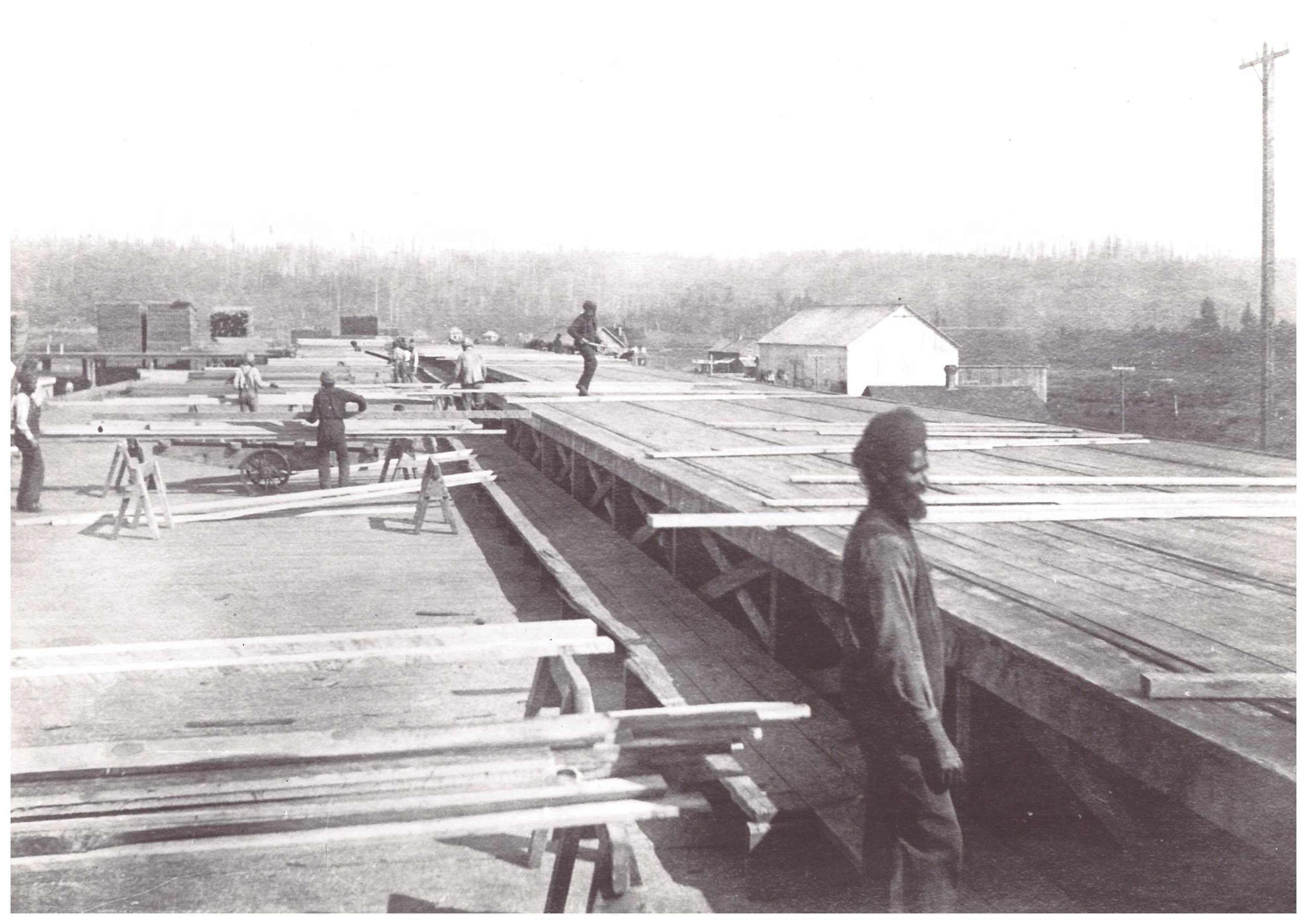

Image (left) credit: A group of North Pacific Lumber Company workers pose for the camera at Barnet Mill, early 1900s. Vancouver Public Library, Accession # 7641, public domain.

Why did they come?

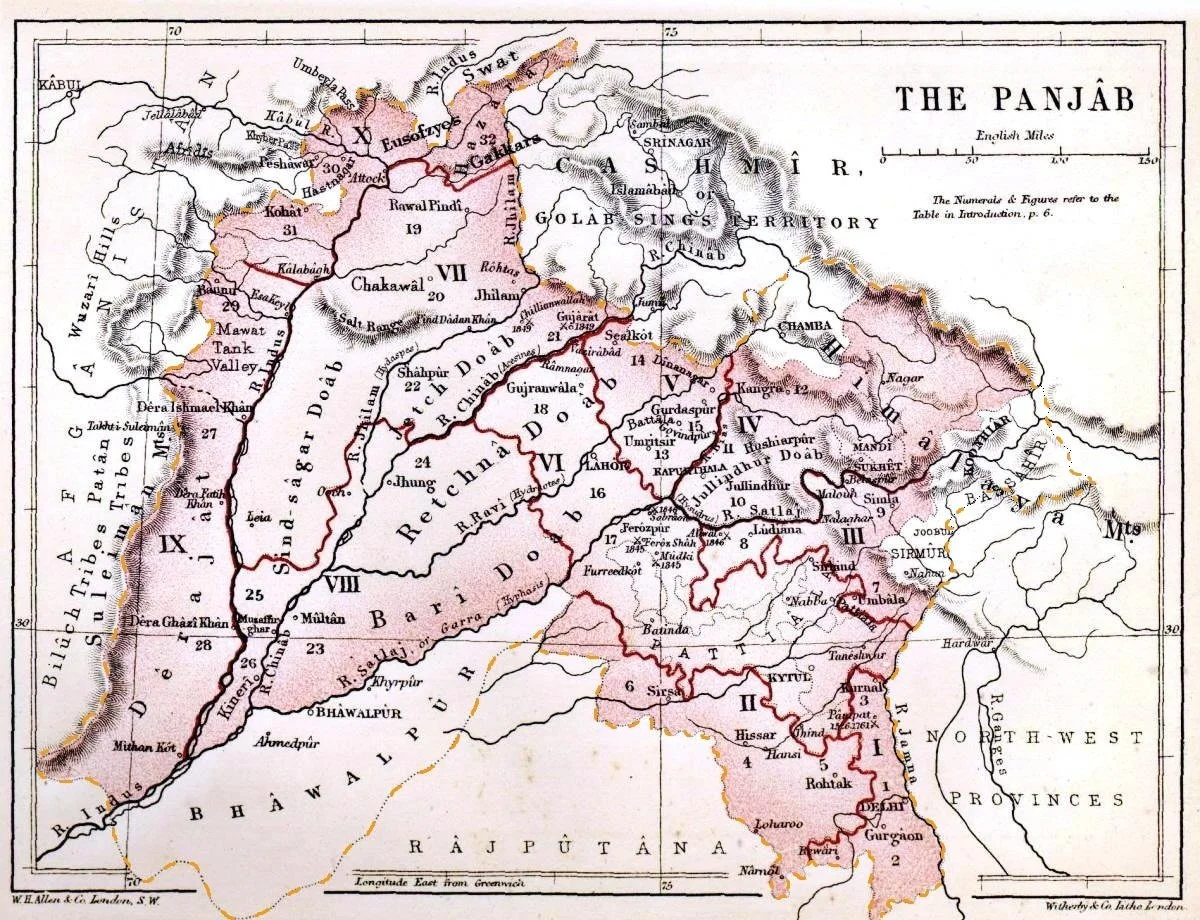

By the turn of the century, the Punjabi peninsula had been part of the British Raj since 1858. This colonial power drew from the population for a large percentage of their military recruitment and put money into developing the region’s agriculture. Though the wealthy landowners did well, the wealth did not trickle down and many Sikh families struggled to make a decent living.

Some of the first Sikhs that came to Canada were soldiers on their way home from England after attending, by invitation, Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. They travelled across Canada on their way back to India and observed, first-hand, the terrain and the possible opportunities.

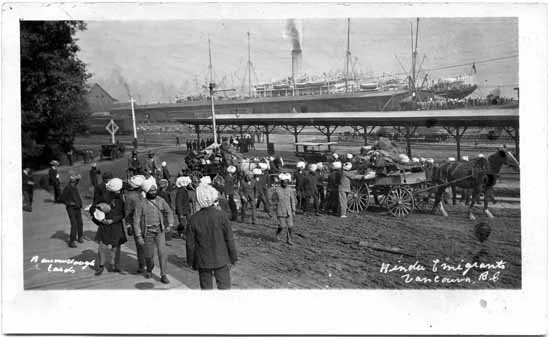

By 1904, forty-five South Asians had come to Canada and were followed by approximately 5000 more up until 1907. The majority of these came to British Columbia.

Then the door to Canada slammed shut, with very few immigrants allowed in until well after WWII. The reasons included racist reactions by both the government and the Caucasian population to exclude Sikhs and other ethnic groups from Canadian society. White labourers feared for their jobs and “foreign” workers were seen as the problem because they worked hard and for less money.

The Journey

“It wasn’t scary for me seeing a ship for the first time, but I know it was for some other people from our village who came with my dad in 1906. Two of them went back to the village from Calcutta after they saw the ocean and the ship in the harbour. They got frightened. It didn’t look very safe. They thought that it might sink in the water and that would be the end of them. They saw the ship moving around a bit in the water with the tide, they said we’re not going to go on that! So my dad came to Canada and the other two went back to the village.”

In the first decade of 1900, many residents in the Punjab area of India were facing hard times and looking for opportunity. Families would pool their resources to send their sons and husbands to find work in Canada. This was not done without preparation. Groups in Punjab formed to teach English, and agents, such as Bhai Arjun Singh, would help people connect with employment. Many of them referred to themselves as sojourners, intending to leave India for a while, make some money and return.

Next came the journey itself. Sikhs had to find their way to Calcutta, a 2-6 day train trip of approximately 2,000 kilometers. With no way to know shipping schedules ahead of time, the travelers stayed at a temple until they could board a ship. Passengers had to bring their own food and cooked it themselves on small stoves. Many preferred this, as it was a way to observe dietary restrictions.

The first stop, 15- 20 days later, was Hong Kong where they were given medical examinations, interviews, and documentation while, again, staying at the gurdwara. Once over these hurdles, they boarded a ship for Canada, at a cost of between $100 to $200. At the time this was a small fortune, yet by 1904 there were 258 Sikhs listed in the BC census. By the 1920s, four CPR ships made the trip between Hong Kong and Vancouver every 15 days. They were the Empress of Asia, Empress of Japan, Empress of Canada, and the Empress of Russia.

“When our boat was still out in the harbour and we approached the city of Victoria, I thought what kind of place is this? I didn’t see any farms or crops, just forest, like a jungle. Where do they get their food? What am I going to do in such a poor country? All I saw were trees, I couldn’t see any big buildings yet, just tiny little shacks. Can this be Canada?”

A New Life: Working THE GREEN CHAIN

Upon arrival in Canada, many Sikhs found work in British Columbia’s sawmills. One of the jobs they were typically hired for was the green chain. It was one of the last stops in production of lumber after debarking, sawing, and edging. This heavy, still green, lumber was sent to a 300 foot long platform edged with chains that conveyed the wood. This was the green chain. Sikh labourers spent long days sorting these planks into piles, according to size. From there it could be put in the dry kilns, or loaded onto wagons and ships.The work was all done by hand. For their labour, they were paid significantly less than white workers.

“You sort of understood that there was a level at which you could function, beyond that it was out of your reach. […] The best jobs, the engineers and people who were the bosses at the mills, went to the Europeans.”

Dedar Sihota, Becoming Canadians.

SIKHS, FRASER MILLS AND MILLSIDE

Fraser Mills employed South Asians (primarily Sikhs), Chinese, Japanese, and First Nations people. Most of these people lived in what was called “Oriental Town” on the Mill property, which was divided into the Japanese, Chinese, and “Hindu” sections. These men lived in bunkhouses that held between 30 and 50 men and had several cook houses where they employed their own cooks and contributed to the needed supplies. When several men worked together, they formed “dining clubs,” and at Fraser Mills, circa 1920s, each man gave three dollars a month to the cook, making his wages approximately $60 a month.

Very few of these men had their families with them. Instead, they worked long hours to save up enough money to send home. Small amounts of money were small fortunes in India at the time.

The first Sikhs who came to work at Fraser Mills, and most of BC, were either single men, or had left their wives and children in India. When the married men finally did manage to bring their families to Canada, they tried to prepare them for the changes they would face. When their wives and children came, they advised them to also adapt. Many women outfitted themselves with western clothing while waiting to sail from Hong Kong.

As many Sikh men discovered in the early decades of the 1900s, looking different was a problem when trying to find work. Many gave up their turbans, cut their hair and beards, and adopted western style clothing in order to make their lives easier. To add insult to injury, white barbers would not cut Sikh hair. Instead, the men went to Japanese or Chinese barbers. These weren’t the only places that restricted entrance. Sikhs were not allowed in theatres or many other public venues.

1880 map of the Punjab, around the time that it was divided into the British ruled canal colonies of Sidhnai, Sohag, Para, Chunian, Chenab, Jhelum, Lower Bari Doab, Upper Chenab, Upper Jhelum, and Nili Bar

Logging with oxen near Millside, Fraser Mills, circa 1889. City of Surrey Archives. F83-0-13-1-0-0-23.

NOT WELCOME

As labourers, women, and babies arrived the white population got nervous. Sentiments went from praising the Sikhs as hard working, decent men, to describing them as undesirable and dirty, among other things. As anti-Asian sentiment rose, so did restrictions and excuses to limit immigrant from Asian countries. The Asiatic Exclusion League formed in 1907 to “keep Oriental immigrants out of British Columbia.” This legislation resulted in race riots in Vancouver’s China town, when upwards of 8000 whites stormed the neighbourhood damaging property and injuring people.

Added to this was the Continuous Journey Regulation of 1908 which meant that immigrants were required to arrive by a single journey, without stops, from their country of origin to Canada. In fact, the CPR ships did make the journey continuously, but the Canadian government stopped this by banning ticket sales for such a trip. This eventually led to the Komagata Maru incident of 1924.

Image: Damage to property of Japanese residents (Nishimura Masuya, Grocer, at 130 Powell Rd., S. Vancouver, 1907.) Library and Archives of Canada, item #3363536.

““On the day that I arrived in 1932.” Mrs. Paritam K. Sangha remembers, “my husband took me to the shop to get new clothes right away. I pleaded with him that I hadn’t had anything to eat and that I was starving, but he did not listen. First, we got the new dresses then later we got something to eat. It was the rule then to dress like the white ladies and keep our hair covered with a scarf at all times.””

Fraser Mills got in on the act too. In 1905 the mill proposed that “no Mongolian labour would be hired,” but in reality they needed the manpower. Anti-Asian sentiment prompted the mill to send a Roman Catholic priest to Quebec to hire workers for the mill that would supplant the Sikh workers. Point “A” on the agreement between the Roman Catholic Archdiocese and Fraser Mills, in 1909, proposes “To substitute, as much as possible, good, honest, French Canadians for Oriental Labour.” They came by the hundreds and established the Maillardville community.

The number of Sikhs in Canada, most of whom were in British Columbia, went from around 5000 to 2000 during this time, and for those 2000, jobs were hard to find and easily lost to white workers. The government even tried to relocate Sikhs to Honduras as cheap labour for sugar plantations under the British Honduras Scheme, but reports from Sham Singh and Nagar Singh, who went to see the conditions first-hand, led to rejection of the scheme.

Image: This image of the deck of the Komagata Maru gives an idea of what it would have been like, stuck on the ship with limited food and water and crowded conditions. Some of the passengers had been on the entire voyage, starting on May 4, and finally arriving back at Calcutta on September 27. Vancouver Public Library, crowded deck of Komagata Maru, 1914, accession #6232. Public domain.

THE FRASER MILLS STRIKE

In 1931 times were tough. Jobs were scarce and the Depression was looming. Fraser Mills began a series of wage cuts and the Lumber Worker's Industrial Union led a two-and-a-half-month long strike. Strikes were common at the time, but what set the Fraser Mills one apart was that it included all labourers, not just the white workers. The solidarity provided by the Chinese, Japanese and Sikh workers was a critical element. Other strikes floundered because these communities often stepped into jobs vacated by strikers. At Fraser Mills they joined the strike.

Among the workers' demands were a ten-cent hourly wage increase, recognition of a union-led negotiating committee, abolition of the scrip system at company stores, and renovation of the living quarters used by Asian workers. They also called for the elimination of Chinese and Japanese, so called 'straw bosses' who skimmed 25 cents off Asian workers' cheques, and who routinely fired any workers they liked, and replaced them with others.

Image: An unidentified Sikh man attends the 12th annual International Woodworkers of America convention at Hotel Vancouver, January 15, 1949. Vancouver Public Library, accession #80796C, photographer Art Jones, public domain.

THE SIKH RELIGION

Sikhism is a monotheistic religion that began in the late 15th century C.E. Sikhs follow the teachings of Guru Nanak, the first of ten human gurus associated with the religion which places importance on the connection between spiritual development and regular moral conduct. These ideas were summarized by Guru Nanak as “Truth is the highest virtue, but higher still is truthful living.”

Sikhs cremate their dead and gather and worship in gurdwaras. One of Sikhism’s most significant gurdwaras is the Harmandir Sahib (Abode of God), or Golden Temple in Amritsar. The teachings of the Guru Granth Sahib echo the religious philosophy of Guru Nanak; to strive for a society based on divine freedom, mercy, love, and justice without oppression of any kind. The details and rich history of this religion could fill many panels. This is a very brief introduction.

SIKH CODE OF CONDUCT

COMPASSION

TRUTH

CONTENTMENT

LOVE

HUMILITY

FRASER MILLS GURDWARA

Long since torn down with the rest of the Millside homes, descriptions of the Fraser Mills gurdwara, built in 1912, are the only visual references found, so far, of the building’s interior. Ossi Thandi was born at Fraser Mills and her grandfather, Jewen Singh, is listed as the “priest” there in a 1923 publication by Rajani Kanta Das, “The Hindustanee Workers on the Pacific Coast.” Ironically, a good description of the temple’s interior comes from one of the French Canadians hired to supplant Sikh labour at Fraser Mills. Though his understanding of what he saw is riddled with inaccurate terms, he nevertheless provides us with a description of the interior.

COMMUNITY

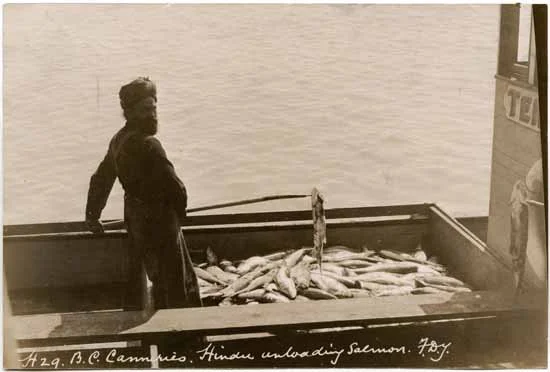

The Sikh community stuck together. They provided each other with company, assisted each other in finding employment, and supported each other in many other ways. When newcomers arrived, those already here helped them find jobs at local mills. Some found work on farms or in fisheries, and many old-timers in Maillardville remember the Sikh men who delivered their firewood.

Image: A Sikh man drives a buggy on Austin Avenue, n.d. City of Coquitlam Archives, item #C6.942

The old-timers were always there for one another. If someone got a bad letter from India, everyone laid their paycheques on the table. If they were in trouble and needed money or someone in their family got hurt or damage to crops happened back home, we all helped. We'd say pay us back when you can, just send the money now.

-Manga S. Jagpal, Becoming Canadian

Mewa Singh worked on the green chain at Fraser Mills. He was also a member of the Ghadar Party- a North American group formed in 1917 calling for independence from Britain. He was hanged for the murder of police officer and immigration official, W.C. Hopkinson. The story leading to this shooting is one of clandestine border crossing, arms dealing and Sikh spies working for Hopkinson. Mewa Singh is considered a Sikh martyr. After his hanging he was cremated at Fraser Mills and for many years a yearly commemoration was held at the Fraser Mills Gurdwara on the anniversary of his death.

“Down in the East Indian community, they would have cremations down where it was real windy, down beside the river. On Sundays, we used to see all these wagons, trucks and cars going down the main street, and we always figured, ‘Oh, oh, something’s going on down there.’ You could see all the people involved were East Indians with turbans. We used to take off along the railway tracks down there. I can remember some of the funeral pyres for the cremations; they always had a wonderful supply of wood, you know, from the mill.”

Rattan Singh at the age when he attended Millside School, 1926-27. Not long after this, he was working at Fraser Mills. Courtesy of Mike Ghuman.

These ladies and children are in a back yard, somewhere in Millside, Fraser Mills, circa 1930s. Mike Ghuman's father, Rattan Singh, grew up with their husbands. Courtesy of Mike Ghuman.

A Sikh man unloads salmon for BC Canneries, 1913. Vancouver Public Library, accession #2052, public domain.